From Democracy Digest:

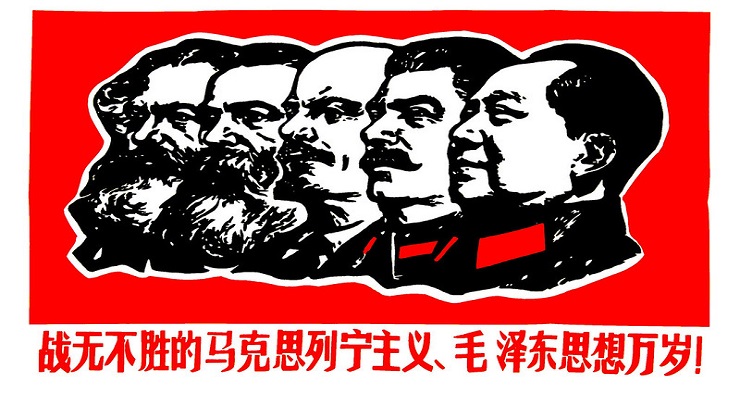

No empire in history has disintegrated as quickly or as bloodlessly as the Soviet one, in the remarkable year that saw the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. Yugoslavia, never a part of that empire, followed a tragically different path; but for the rest of central and eastern Europe, though clearly imperfect, the past 30 years have been a time of marvels, the Economist notes: …

With the collapse of Communism, “the ‘ideological lie’ had been exposed as the chimera it had always been, and the peoples behind the Iron Curtain cried out for a ‘normal’ existence, freed from violence, lawlessness, and systematic mendacity,” Daniel J. Mahoney writes for Law & Liberty. “The economic motives and concerns were real but secondary. People can tolerate poverty, at least to some extent, but not the spiritual poverty of a regime built on force and deception.”

The result was a quite paradoxical moment for democracy, notes Luke Cooper (@lukecooper100), a Visiting Fellow on the Europe’s Futures program at Vienna’s Institute of Human Sciences and an Associate Researcher at the LSE Conflict and Civil Society research unit. As a system of representative governance, it was more widespread than ever before. Yet, as conflicts over big ideological ideas were pushed to one side by the unfettered rise of neoliberalism, the representative function of the democratic system was diminished. Two key dangers presented themselves, he writes for the LSE blog:

-

- Firstly, the existence of communism had acted as a moderating force on capitalism. Once it was no longer a threat to the status quo there was less incentive for capital to compromise with labour.

- Secondly, if the purposefulness of democracy became less clear to voters, then participation was likely to decline. Ultimately, radical criticisms of liberal democracy might re-emerge. If citizens grew disillusioned they may end up rejecting democratic processes….

Read the article here.

Leave a Reply