In Honor of Black History Month

The narrative of the labor history of African-American women has a very important place in the chronicle of American society. Long relegated to the most arduous, backbreaking, low-status work since American labor history “began,” the African-American woman has had to step over the mounting pile of responsibility to family, duty to husband, racial discrimination in the workplace, sex discrimination within her own race, gender inequality, and barriers to higher education before she has finally been able to visibly emerge onto the scene of the high-status corporate, scientific, and entertainment worlds, to name a few among the many she has been able to penetrate.

The backstory of the African-American woman’s labor experience spans the entire landscape of the labor economy and market, and it has been against a backdrop of ongoing contentious social change and the struggle to realize her identity.

Historically, the proportion of black women participating in the labor market has outweighed that of white women; and, it is likely that, in their struggle to be gainfully employed, black women have had to work more hours during their life than any other group in American labor history. These and other observations bring their labor history to the forefront of the female black experience in American society.

Labor and Sexism in U.S. History

The labor history of African American women partly parallels that of all American women, especially when it comes to restrictions and exclusions. All women in America, initially, from the time the colonies were established, were confined to the domestic realm.

But, after the American Industrial Revolution during the latter half of the 19th century, middle class white women with working husbands had the responsibility of taking care of their home and children; black women did the same, but had to also work a menial job, commonly in a white family’s home, to help feed and clothe their families.

But, women’s domestic responsibilities extended beyond the management of the household; the ideal of comprehensive caretaking included another responsibility—derisively pointed out by Gertrude Bustill Mossell (1855-1948), a black journalist and women’s suffrage activist, as it pertained to black women: black women were expected to “always meet their husbands with a smile…to do a host of things for his comfort and convenience.”

This sexist concept did much to prevent the idea of equality in the home between husband and wife—and father and mother in the eyes of the children—and it pervaded the work realm outside the home.

Traditional gender roles and labor

Sadie T. M. Alexander (1898-1989) was the first black woman to receive a Ph.D. in economics in the U.S. and also the first black woman to graduate from law school at the University of Pennsylvania. Alexander was among the early black feminists who voiced her recognition that the restriction of work to the domestic sphere, whether paid or unpaid, was the reason women were conventionally viewed in the workplace as subservient to men.

As Alexander pointed out, prior to the start of the American Industrial Revolution, production was home-based, and women played a big role in the process; then, the revolution created a shift to factory-based production. Men, as a result, left the home to sell their labor for wages, while women remained at home to perform unpaid domestic work. The woman’s role as the caretaker of the household became even more entrenched.

It was not until World War II that American women were able to utilize their skills in occupations other than domestic service. The stress of maintaining war materiel production, given the withdrawal of three million men from the workforce to participate in the war, resulted in the shift of women from the home to the factory.

However, in the wake of the war, these jobs ceased to have immediate purpose and disappeared, and, as a result, most women workers were forced to return to their previous jobs. Many white women had the opportunity to return to their pre-war clerical jobs, which were not as well paid as factory work, but still better than the domestic jobs to which most of the black women returned.

This just showed how black women were the most economically vulnerable workers in America. According to the Women’s Bureau of 1948, “white women workers [are] having median earnings more than twice as high as those of non-white women workers (mainly black women) [who are] earning less than $500 a year.”

Alexander blamed the low wages on the fact that black women were virtually entirely excluded from post-war factory workplace and other higher skilled jobs, and, again, consigned to the most menial and underpaid domestic services. As women progressively gained entry into colleges and universities in the 20th century, black women realized it would take education to elevate them in the workplace.

Education and women workers

In a piece by Mossell entitled “A Lofty Study,” she described a visit to another woman’s home in the Religious Society of Friends, during which she had a moment of epiphany. The woman took Mossell up into her attic, to her study. Mossell described how the room was practically mesmerizing—a mindful personal space. The sight of this room aesthetically pleased her so much, and it made her realize what she lacked in her own home environment. Amazed that she had never before recognized the need to nurture her creative sensibility, she was also surprised that she never thought of simply providing herself with at least a “corner in some cheerful room” where she could contemplate and explore ideas and write.

While Mossell seemed to believe that black women still had the primary responsibility of taking care of their children and husbands, she saw the need for them to be able to experience a separate, private space to foster their intellect.

Black women have made gains over the past half century in cultivating their intellect and their creativity as we’ve witnessed how they’ve attained higher education, and—while still clustered in the service sector—have been able to broaden their representation across an array of higher-wage service occupations and professions.

During this time frame, in the fields of education, the arts, medicine and politics, black women have established highly visible and enduring careers, albeit distinctly fewer in number than their male and white female counterparts, but no less respected. I would suspect it would be to Mossell’s delight; it is an impressive observation as a very large proportion of black women were still predominantly working in the lower service occupations as recently as in the late 20th century.

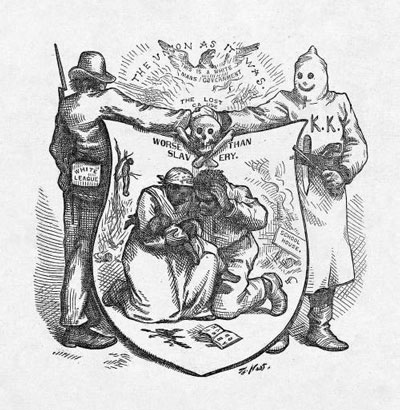

Entrenched societal racial discrimination

Those that “made it” had a challenging path to success: discrimination because of their color prevented black women from getting the better paid jobs available to white women. Insofar as entrenched societal racial discrimination thwarted the efforts of black women to get meaningful jobs, it was also the sex discrimination black women faced in their own community that perversely prevented them from realizing professional success.

According to Frances Beale, a black feminist and peace justice activist, this “double jeopardy” of being black and being a woman was what largely denied them access to the working world. Beale described how there were black men who, in their attempt to continue to exert male dominance, would emphasize that their women would best step back into domestic, submissive roles. She also described how many black women grew up brainwashed into thinking this was their place and lot in life, that their only purpose was to serve as a housewife.

Beale explained that it is essential for black men to realize and accept that each member of the black community—woman and man—had to be as academically and technologically advanced as possible, because otherwise, racism would continue to have an excuse to exist.

She believed that to “wage a revolution, [the black community] need[ed] competent teachers, doctors, electronics experts, chemists, biologists, physicists, political scientists…black women sitting at home reading bedtime stories to their children [were] just not going to make it.”

Beale believed that in order for there to be a liberation of black people, black men and women had to unite in their rise to power. But, to do that, they needed—the women needed—to feel equal.

African-American women workers today

While Mossel and Alexander have since passed, Beale is still very much alive and remains politically active. When interviewed recently by the social justice organization, Street Spirit, and asked whether racial equality has improved, she said she believed progress had been made for the black community, “but, we still have a long way to go.”

To make her point about how race is still a defining issue insofar as educational and economic issues are concerned, she cited the backdrop of the troubling Trayvon Martin case, which spoke to the ongoing, deeply-rooted, racial injustice that still exists in America. A large part of the reason why racism is still an issue, she thinks, is because the black community itself has still not yet resolved the issue of sexism within its own ranks.

On the positive side, were Mossel and Alexander still alive today, I would expect that they would take note of the progress that has been made since their time.

Not only are there black women in the higher echelon professions, there are black women at the pinnacle of their fields, setting standards that all would aspire to. Oprah Winfrey and First Lady Michelle Obama, known and admired not only in our country but throughout the world, has earned the respect of millions. Then there’s Ursula Burns, CEO of Xerox, and RisaLavizzo-Mourey, CEO of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and Condoleezza Rice, former Secretary of State of the United States.

However, notwithstanding these high-achieving stars, high unemployment among black women in the U.S. still looms large, and at nearly twice the national average. According to the Institute of Policy Research, in 2014, black women had the highest unemployment rate among women, 10.5%, compared to white women, 5.2%.

While “traditional” overriding barriers such as racial and sex discrimination have been crucial, as written above, in undermining the upward mobility of black women in the workforce, there are also barriers newly developed over time, including name discrimination, wage discrimination, unfair use of criminal and background checks, and workplace discrimination.

Single-parenthood among African-American women

Arguably, however, the biggest barrier that thwarts the working black woman’s ability to realize her full potential stems from a pervasive cultural problem that puts her in the very difficult position of having to single-handedly maintain the household while working long hours outside the home, and that is the alarmingly high rate of single-parenthood among African-American women. Too many black mothers, 66% according to United States Census Bureau data, are single parents.

As the only breadwinner, they find themselves struggling economically, many relying on financial assistance food stamps for survival. While many try to attend college, there are instances and a sense of organized discouragement: public aid workers, for example, have been cited as discouraging black single mothers from earning college degrees.

As one African- American woman stated in an article in The Atlantic, “unless you’re doing training to become a home health aide… [the caseworkers] just want you working. Don’t they understand I’m going to college so that I don’t have to use my benefits anymore?”

Conclusion

Mossel, who strongly advocated for highly-skilled professions for African-American women, and Alexander, who fervently believed in the importance of intellectual advancement, would probably be stunned by this and it would redouble their their efforts to fight for economic and educational rights more than ever before.

Finally, it must be acknowledged that the imagery often portrayed of lazy black women who refuse to get a job and keep having kids is an optic that distracts the public from meaningful dialogue, and action, about the destructive disparities of poverty, racism, and sexism. The struggles of black women in America must be heard. And, their resilience and determination through it all must be recognized. Once they, too, are educationally and economically empowered, American society will benefit as a whole.

Sources

- “Frances Beal: A Voice for Peace, Racial Justice and the Rights of Women.” The Street Spirit, May 2015.

- Freeman, Amanda. “Single Moms and Welfare Woes: A Higher-Education Dilemma.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 18 August 2015.

- Guy-Sheftall, Beverly. Words of Fire: An Anthology of African-American Feminist Thought. The New Press, 1996.

- “The Status of Women in the States: 2015 (Full Report).” Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

Crystal k. says

I think this is a good article. The only thing I don’t agree with is the part when you state that “All women in America, initially, from the time the colonies were established, were confined to the domestic realm.” To me you are leaving out slave labor which african American women did particpate. Even though they didn’t get paid for it, it should still be considered as work in my opionion.