From ProPublica and written by Nina Martin:

As more states adopt laws that could restrict turnout, Kenneth Glasgow and his allies are pushing to extend the vote to millions of ex-felons. Will the flimsily supported charge against him undermine this movement on the verge of its greatest success?

This story is a collaboration between ProPublica and New York magazine.

The last weekend in March, Kenneth Glasgow had planned to be in Atlanta strategizing with other Southern organizers about how to help pass the Florida ballot measure that would result in the most sweeping restoration of voting rights for felons in well over a century. A former inmate himself who’d served 14 years for robbery and drug crimes, Glasgow is a pioneer of the felony enfranchisement movement — an Alabama minister and activist whose righteous indignation alone usually exceeds the energy of three people. At the very least, he needed to be back in Georgia by Monday morning to train people from across the country how to go into jails and register inmates to vote. But now he was preoccupied by his other job. “Pastor Kenny,” as he’s known around his hometown of Dothan, is a sort of social-worker-in-chief for the most down-and-out people in one of the more down-and-out places in the Deep South, a mostly black section of the city called “the Bottom.” As it happens, he’s also the half brother and nephew of the Rev. Al Sharpton, a fraught piece of family history that has shaped his life for ill and for good.

That weekend, a close friend who’d been staying at a halfway house run by Glasgow’s small nonprofit, The Ordinary People Society (TOPS), had been charged with assault after a gun altercation. Now, on Sunday night, Glasgow needed to bail the guy out, collect his things from the halfway house and escort him to drug rehab. Before that could happen, however, a 26-year-old named Jamie Townes stopped Glasgow in front of the squat brown duplex that serves as the halfway house. A reputed drug dealer, Townes had a habit of leaving his Monte Carlo running on the street, and he’d gone out around 10 that evening to find that his car had vanished. Townes figured someone had taken the Monte Carlo as a joke — would Glasgow help him find it?

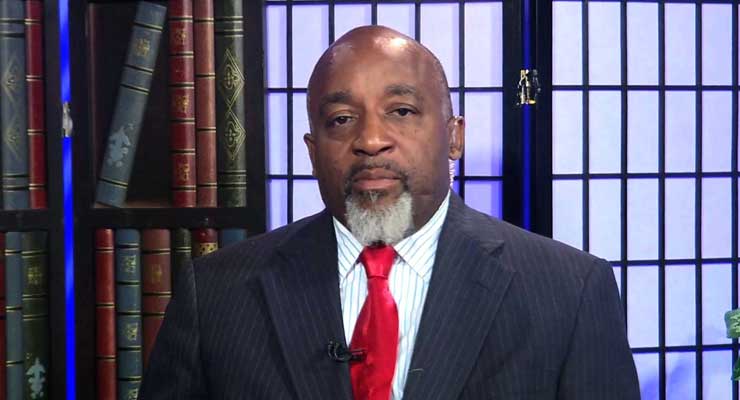

Glasgow agreed, begrudgingly. He said he didn’t know Townes well, but in a neighborhood where many people don’t have cars or driver’s licenses, and public transportation is nonexistent, Glasgow said he carts five to 10 people around every day. “It’s normal for me to take people to get their Social Security card, go to the store, take them to see family,” said Glasgow, who is short and sturdy, with a bald head and a scraggly white goatee. In this instance, “I was like, ‘Ugh, I got to get back to Atlanta, man.’” But if he refused to help, “I’d lose all respect in the neighborhood: ‘What kind of dude are you that won’t take someone to look for a car when you’re the only one around with a car?’”

Except that night Glasgow didn’t have his car — he was borrowing a friend’s, a new black Camry. So he and Townes, along with the man expected back at rehab and his female friend, piled into the vehicle. Within a few minutes, they spotted the missing car as it turned a corner. Its hood was badly crumpled, and it was headed right toward them.

The Monte Carlo hit them hard, clipping the Camry’s driver’s side. Glasgow tried to back up, but something bumped them from behind, he said, as if they’d been tailed by a second vehicle. Now Glasgow really panicked: Were they being ambushed? Had they wandered into a gang war? “Put your head down, put your head down!” he yelled at his passengers. He said he then heard two quick bursts of gunfire. He pressed himself lower in the seat and waited.

The police arrived almost as soon as the shooting ended. Glasgow watched them inspect the Monte Carlo, which had come to a stop 60 yards up the road. Townes was up there as well, talking to a couple of officers. Glasgow said he’d been too busy taking cover to notice the younger man slip out of the car. It was at police headquarters that he learned the identity of the person who’d stolen Townes’ car: a 23-year-old woman Glasgow had never heard of, named Breunia Jennings. Even before taking the car, she’d been acting strangely that day, ranting on Facebook, shaving her head. Now she was dead.

The killer, police said, was Townes; the weapon, a .40-caliber Ruger semi-automatic pistol he’d brought with him when he and Glasgow went hunting for his car. Townes was being charged with capital murder.

So was Glasgow. Under Alabama’s complicity law, anyone who knowingly abets a crime is just as culpable as the person who commits it. The charge was beyond frightening for Glasgow. Capital murder is punishable in Alabama by life in prison or lethal injection, and Houston County not only has the second-highest incarceration rate in the state, but also, as of 2013, had more people on death row per capita than any other county its size (or larger) in the country.

And the murder charges risked hamstringing one of the felony voting rights movement’s most effective leaders at a critical juncture. If Glasgow and his fellow advocates could get Amendment 4 passed in the all-important swing state of Florida, it would be a victory over some Republicans’ efforts to employ a grab bag of tactics to suppress and dilute the votes of blacks, immigrants and liberals. Practically overnight, 1.4 million people would be eligible to cast ballots, one of the largest influxes of new voters since women’s suffrage became the law of the land.

Glasgow moved in a haze of shock as a camera took his mug shot, as he changed into an orange jumpsuit, as a guard pushed him into a cell. He kept thinking: This is crazy. I’m innocent, I’m innocent. But also: You finally got me. You finally got me.

See more here.

Leave a Reply