What Would be the Worst Scenario Using the Approval and Score Voting Method? A Defecting Faction.

By Michael Ossipoff

In the following article I will discuss the use of strategy in a defection situation in greater detail in order to explain what it would be like, as well as the variety of options and the power, conferred by even the simple Approval voting system.

Suppose that there is your favorite (F), a compromise (C), and a worse candidate (W). It’s the classic chicken dilemma. The people who like F best are “F voters”. The people who like C best are “C voters”. The people who like W best are “W voters”.

By the definition of the chicken dilemma, the F voters and C voters regard each other’s candidate as second choice, and consider W their last choice. In other words the F voters consider C their second choice, and consider W much worse. The C voters consider F their second choice, and consider W much worse.

For example, the F voters plus the C voters add up to a majority, so that, by sharing approvals (this is an Approval or Score election), they can ensure that W won’t win. But the trouble with that is that it requires co-operation, by one or both sides. And if only one side (F or C voters) co-operates with the other, then the co-operating side might lose, taken advantage of by the other faction with whom they co-operated.

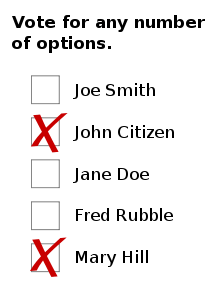

There are five distinct kinds, levels, of support that you, as a F voter, could give to C, under various circumstances. I’ll number them:

1. Full Support, Max Rating:

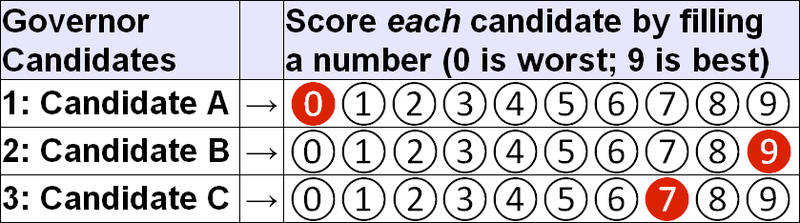

Of course, in Approval, max rating is an approval, 1 point instead of 0. In 0-10 Score, that’s 10 points. If F and C are acceptable to you, and W is unacceptable, then, as I’ve said, your best strategy in

Approval is to approve (only) all of the acceptables. In this case, that is F and C. Even if the C voters are critical of F and his/her voters, even if the C voters are inclined to defect, that doesn’t change the fact that C is acceptable and W is unacceptable.

Strictly speaking, your optimal strategy is to approve C, even if his/he voters are inclined to defect. However, that depends partly on how long this has been going on. If it’s the first Approval election, and we’ve yet to elect anyone better than W, then certainly the wish to do so predominates. Elect someone in {F,C}.

Later, in subsequent elections, we can sort out which should win. But what if it’s the second Approval election and you’ve already elected C, because the C voters defected? Or maybe that’s been going on for even longer. Maybe there comes a time when it’s time to insist on fairness to F, and his supporters, including you. That’s when you switch to rating levels 3 to 5, below.

It depends also partly on how likely it is that C will outpoll F and how likely it is that you need C. It depends also partly on how badly C and his/her campaign people have been badmouthing F. But, basically, at first, when you don’t care which of {F,C} win, as long as one of them does, you have good reason to give a max rating to both.

2. Both Factions Co-operative, But Wanting Bigger Candidate to Win:

What if the F and C factions are fully co-operative, but they both want the bigger of their two factions to win. The trouble with number one above is that, if both sides co-operate in that way, it will be a tie between F and C. In practice, if there are even a few defectors, the winner, between F and C, will be decided by the matter of which faction contains the most defectors.

That may be ok the first time—who cares, as long as one of {F,C} wins. But, later, as an ongoing co-operation between the factions, we could do better: Suppose that both factions give to each other’s candidate .99 maximum. I’ve discussed, in the article “Brief General Outline-Summary”, how to give fractional ratings (such as this .99 maximum) in Approval and 0-10 Score.

The result will be that, in a large election, if the F & C factions add up to a majority, and all of their voters co-operate in this way, then the larger of those 2 factions will win.

3. Chicken Dilemma” but primarily avoid mistakenly not helping C

We don’t have the co-operation needed for number two, and number one might no longer feel appropriate or right to you. So we go down a step, for rating C. This is where SFR starts. I’ve already defined SFR (Strategic Fractional Rating), but it can be described briefly, so I’ll say it again here:

The idea is to give C just enough of a little boost so as to be able to close the gap between C and W, to make C outpoll W, if C is big enough to already be able to outpoll F (because that’s what would make C qualify to be the rightful winner among {F,C}); but not enough to make C win if C isn’t already big enough to outpoll F. I’ll refer to this as “conditionally helping C”.

For this support-level, number three, you still are inclined to help C enough so that you want to be sure of conditionally helping C even under the most unfavorable likely circumstances, when W has as large a population share as s/he is at all likely to. You want to try to avoid mistakenly failing to help C.

4. Chicken Dilemma–primarily avoid mistakenly helping C

Maybe because C seems particularly unlikely to outpoll F, or because you especially dislike C, or because the C faction has been winning by defection for a long time, or because C, his/her campaign people, or his/her faction, has been majorly badmouthing F, maybe making sure that you don’t mistakenly help C feels more worthwhile than making sure that you don’t mistakenly fail to help C.

So, the important consideration for your SFR of C is that you want to conditionally help C (as defined above) only under the most favorable circumstances. In that way, favorable circumstances (low support for W) won’t result in your helping C win by defection.

Number four differs from number three in regards to what you most want to avoid.

Two things I would like to point out about number three and number four are: first, of course there could be gradation between numbers three and four. They’re just extremes. So, even if you could reliably calculate the exact fractional rating that would achieve number three or number four, with sufficiently reliable information and the right formulas, you still might want to give something in between number three and number four, depending on how much you dislike C, or on the other circumstances by which I described the choice between number three and number four.

Secondly, of course, though it might well be worthwhile to use a formula (like those that I described in an earlier strategy article here) to choose SFR for number three or number four, the assumptions governing choice of formula, and the numbers to put into it, are subjective guesses anyway, making the process subjective, even when using a formula.

Therefore, it’s really just as good to subjectively and intuitively judge what fractional rating to give to C. You don’t need to use a formula. I just felt that I should mention that as a hypothetical basis for the SFR. You could just as well, intuitively and subjectively choose the right-feeling fractional rating for number three, number four or in between.

5. Zero Rating.

Maybe the conduct of C and/or his/her campaign people or faction has been so bad, in the ways I spoke of above, that C deserves a 0 rating from you.

To reiterate, C voters don’t have any more predictive information than you do, and, therefore, SFR’s defection-deterrence is genuine. This defection situation, chicken dilemma situation, is the closest thing that Approval and Score have to a problem. It’s the only thing that could pass for a problem in Approval or Score. I’ve discussed a whole list of reasons why chicken dilemma won’t be a problem. Some of the reasons are as follows:

A. Defection by C voters will spoil F faction’s support for C faction in subsequent elections.

B. Conversations and discussions and public instructions will make it impossible to conceal intended defection

C. Tit-For-Tat strategy: Defect or co-operate, as C voters did in the previous election.

D. Agreement between C and F, or their campaign organizations and/or voters, for co-operation (number one or number two).

E. The weakest argument, in my opinion: Principled refusal to co-operate. Though I don’t like this solution, it’s widely used successfully in the animal kingdom.

F. SFR, described in detail above.

My purpose here has been to show what the worst situation would be like in Approval or Score, and that it wouldn’t be bad or difficult at all as well as to provide a better example of what Approval and Score are like, and to show their appeal and the power that they give to the voter.

Leave a Reply