When I First saw an American Relativism Emerging

I was a native Californian in my freshman year of undergrad in New York, heading to my godmother’s for Thanksgiving in New Jersey. It was just after the re-election of President Obama. As an idealistic political science major, the first few months of my undergraduate education had fuelled an urge to test my beliefs whenever I had the opportunity, albeit non-combatively.

My godmother’s home was a comforting extension of my own back on the west coast, an all-embracing residence of love, food and laughter. But they were also culturally different, starkly so. I was a Los Angeles Jew (culturally, not a practicing one) surrounded by an eclectic mix of orthodox Christian Syrian and Lebanese immigrants, about half first generation and half second. The family, appearing so vast and crowded in the house as if the family sustained its own sub-culture, bought full force into the American dream, relentlessly climbing to reach a middle-class lifestyle. My godmother being my godmother,invited church friends and other friends of unknown friends that seemed to blend in with my godmother’s family that weekend, all nearly indistinguishable and all came from middle-eastern, Christian orthodox families.

Though my godmother described me as the “California liberal” coming over for the holiday, I was never a completely isolated one. I had been exposed to various brands of conservatism through family friends, especially the machismo strand as a high school athlete. Injustices and inequalities enraged the idealist in me, but even Republicans I previously exchanged with as an ebullient teen acknowledged certain basic injustices and inequalities that needed correction. The magnitude, life valuesor policy prescriptions between us seemed to be the dividing factor. So, I had a sort of binary sense of how political realities could be seen by people, that there was at least a foundational set of truths politically passionate people acknowledged and formulated opinions from.

My godmother’s husband evinced a stentorian presence, despite being of average physical size. Irascible and aggressive one minute, and excessively altruistic the next, he had an incredible wit for insults and subtle sardonicism. He was fun and entertaining to be around, a reminder of the street smarts I was missing out on during my liberal arts education. A passionate second-generation Syrian with an omnipresent foul mouth, exuding authentic Mafioso instincts as much as he feigned a church going soccer dad persona, he was fond of provoking my liberal idealism through a visceral and almost burlesquing kind of conservatism. I usually laughed at the provocations because it was him, a rough on the edges east coast coprolaliac who I believed had a higher than average ability to detect bullshit.

But the night before Thanksgiving he wanted to honestly assess my political views, match his reasoning with mine. He waited until the family was asleep, summoning me to the downstairs office in the basement where he could discreetly light up a cigarette, mellow the brain cells and control the tempo of his thoughts. Wearing a guinea tee, and inhaling and exhaling slowly but confidently, he asked me about climate change: “You still believe in that tree-hugging bullshit your professors keep telling ya about?”

Since he, believe it or not, appeared more serious about this discussion, I confronted him with very basic evidence that, indeed, a consensus in the climate science community has been reached on man-made climate change, and that, to boot, “you can’t name a single advanced country that has a major political party that challenges the reality of man-made climate change except for the United States.” After challenging me to look it up and show him, as well as a demand for a scientific breakdown of the greenhouse effect, he favored the Glenn Beck version of climate change instead.

He was a busy man, and so even though his view on the issue was gathered from the equivalent of political a snake-oil salesman – and God knows where else – I did not want to fault him for it. He was genuinely inquisitive, unlike many others I politically agreed with, and there was a clear logic to the way he sought to challenge my knowledge of an issue I acted so confident in discussing.

In an effort to make him trust my logic, and thus create some willingness for him to at least explore more rational and empirical sources of information later, I sought to broach an issue with which we would probably agree: the Syrian civil war. I assumed he’d have an acute knowledge of the situation, given that relatives of his were still trying to make their way to the U.S. from the country. Moreover, he was not a neo-con. He did not support American foreign intervention in the Middle East nor America’s ubiquitous army bases around the world.

But I quickly learned how naïve and unexposed I was. Gathering my news from the Syrian civil war through fairly respected sources like The New York Times, Human Rights Watch and the UN, among others,I thought the only debate to be had was on American intervention in the country.

Instead, my godmother’s husband claimed that Assad was a rational and justified actor, saving Christians and secularists from Islamic terrorists. In response to my contention that Assad, by all respectable accounts, is a war criminal whose only devotion is self-preservation and hence needed to delegitimize the West, he went further, alleging that Saddam Hussein had not used chemical weapons against his own people and that the recent overthrow of Gaddafi and our actions in the Middle East, in toto, was part of a larger CIA hatchet job. Sure, the CIA had committed and orchestrated some egregious crimes and coups since their inception, but this was unsubstantiated nonsense.

I was less stunned at these nonsensical views as I was about why he dismissed so many respected and diverse sources. A common retort from him, to this day, is “Well, how do you really know that’s true?” His views were reliable instead, according to him, because he spoke to people inside Syria who knew the internal reality, and that Americans were fed propaganda to make Assad and other Middle East dictators look worse than they were. He eschewed making necessary religious distinctions on his sources back in Syria, I would later realize.

On Thanksgiving night, after a fun and truly enjoyable dinner, a group of the elder Syrian men summoned me down to the smoke-filled basement again, wanting to debate the young, naïve California liberal at their dinner. Perhaps for the entertainment, but their tone suggested otherwise.

I became a representative of a rare opposition to a good, and the men were far more antagonistic than my godmother’s husband, who, despite my calm demeanor, had to warn me not to probe certain subjects too deeply with the elders. Yet these men all led busy, respectable lives outside the sphere of politics or academia but still appeared confined to their church or ethnic communities outside of work. They were tense, anxious, in an almost fearful way. While I was eager to listen, I also felt the information that led them to their beliefs were quite dubious and myopic.

Their views were worse than I imagined. Starting with an unclear interpretation but strong confidence in anthropometry- the long debunked justification for white superiority over blacks (used to suggest blacks were inferior because of their skull size), then veering into theories that the CIA was currently funding Islamic terror groups for a nebulous goal the elder men couldn’t articulate but leaned on the word “elites” to make seem more reasonable, and the idea that the U.S. government was promoting homosexuality in the population, all while asserting throughout how much they loved the United States.

Alex Jones was gathering a large underground following of conspiracy theorists by this time, and even some respectable politicians and reporters (including one I interned for and still admire today) appeared on his show from time to time. My friends and I occasionally watched him for the laughter, since he seemed to be no more than a caricature, a zany conspiracy theorist who threw in some sprinkles of rationality from time to time to keep the increasing popularity sustainable.

Oddly enough, many of the conspiratorial views that Thanksgiving weekend seemed reminiscent of Alex Jones’ unhinged rants. For example, the idea that the CIA was arming and funding radical terrorist groups-including Al-Qaeda and later ISIS – in Syria; or that Bin Laden may not have really been killed or was killed long before the government announced he was, since there wasn’t a picture released; or the idea that Assad’s war crimes were fabricated by the U.S. government (Assad’s later chemical weapons attack deemed a “false flag” by Alex Jones). It was one thing to be sceptical of government released information, it was quite another to be so confident in alternative and radical theories without sufficient evidence.

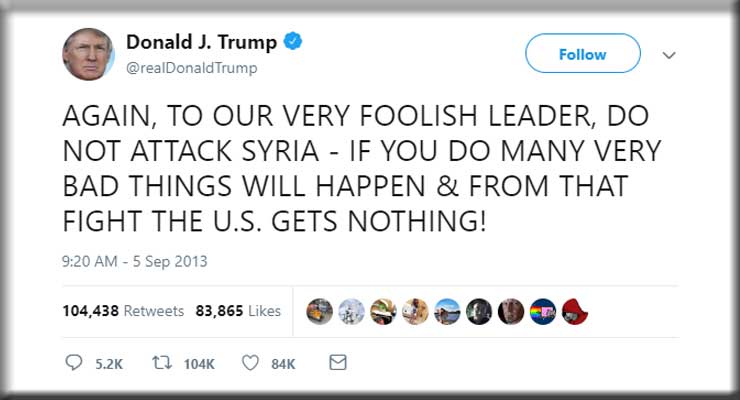

By 2015-16, long after that Thanksgiving weekend, interesting and ominous events were occurring that made that weekend stand out: ascendant Eastern European nationalism, reaction to U.S. sanctions on Russia, Russia’s increasing global presence, and Assad’s use of chemical weapons against his own people. Many of these issues were front and center in American political discourse, but the context for these complex issues and their patterns-patterns also emerging in America-was insufficient.

The news media, by and large, failed to explain striking similarities between Russian, Eastern European and Syrian propaganda. For example, the Assad regime’s violent force against resistance in 2011 was and continues to be accompanied by cultural propaganda and a complex reliance on loyal religious groups, especially Christians within the country.

Lisa Weeden, a veteran researcher on Syria, notes the importance the regime places on lifestyle and cultural propaganda, orchestrating television or radio programs on makeup and an upper middle class lifestyle while seguing from those shows into serious interviews portraying America at “the heart of the conspiracy” against the Assad regime and in favour of terrorist groups.

Further, Weeden points out that in the Bashar al-Assad era, truth became more difficult to discern, as it aims to blend economic stability with the Assad regime so that beneficiaries of the regime overlook or even favor the atrocities by his regime against the threat of destabilization. Fears of destabilization from groups that benefit from Assad are especially prone to the regime’s propaganda, i.e. that all opposed to the regime present an imminent threat to the country’s stability.

Similarly, the rise of Eastern European nationalism in Poland, Hungary, Romania and the Czech Republic has mirrored Putin’s investment in anti-western sentiment through state television, while also employing anti-semitic and economic nationalist appeals that fit specific cultural contexts. This is conveyed through, for example, ubiquitous propaganda against George Soros, and the imminent need for collective patriotism and sacrifice against western hegemony and their lust to make the East submit to them. All the while, fascist and authoritarian policies and tendencies are largely overlooked against the broader enemy.

Take, for example, Hungary’s massive anti-corruption protests in 2017, in which protestors were portrayed as recipients of Soros money. This was entirely false, and a major news network was actually fined for the dubious claim.While one could well argue on American imperialism, pursuit of hegemony and real politik without priority for human rights in America’s foreign policy history, where did these other wild conspiracies emanate- ranging from American funding of Islamic terror groups to George Soros’ fiendish mission for a New World Order?

It struck me that Alex Jones’ conspiracies, right-wing Eastern European propaganda, Assad’s propaganda, and the reality flipping views I heard that Thanksgiving weekend were eerily similar. Syrian Christians, largely supportive of Assad in Syria, embraced the regime’s propaganda which delegitimized the West just as the Russians, who in turn helped prop up right-wing nationalists in Eastern European countries. Alex Jones’ propaganda mirrored this by sprinkling in valid criticism of U.S. foreign policy and civil liberties while connecting them to larger and dangerous conspiracy theories. Like right-wing, Eastern European propaganda, Alex Jones refers to George Soros as the “head of a Jewish mafia”, and suggests that a “Soros linked group was behind the chemical attacks in Syria”, among a litany of other things Jones deems Soros responsible for. As Jones’ popularity has risen, many Republicans, from Sen. Mike Lee to Wayne LaPierre, have bought into similarly outlandish theories (albeit not as extreme in most cases).

This is where we come to today. Alex Jones has interviewed, and is praised by, the President of the United States, fake online news has emerged as a new challenge to democracy, Russia plays an ever increasing global role-especially in Syria and behind the scenes in the greater Middle East- while evidence indicates the President of the United States may have very well been compromised by the Kremlin, and the Republican base stands readily subservient to the edicts of Trump and alt-right conspiracy ramblings without challenge.

But this has been brewing, and even if the majority of Americans do not believe unsubstantiated and often dangerous conspiratorial theorizing, it has enveloped an entire base of a major party in power and news network (Fox). This is not simply about delegitimizing the media as “left-wing”, as the Republican Party achieved far earlier. The level of acceptance in more dangerous conspiracy theories about our government, and society in general, has eroded democratic institutions throughout history and the world over. Trump has tapped into an American insecurity, now manifested into an emerging American relativism. Paul Manafort, former campaign chairman now charged with a 32-count indictment by the Special Counsel, and others who understood right-wing, nationalist appeals in Eastern Europe on his campaign, knew all too well these strategies.

My godmother’s family was not an anomaly, I came to find, and even though their willing embrace of a despotic war criminal appeared detestable on the surface, they were convinced it was the moral, Godly sanctioned view. While the reality has begun to set in that we are living in a vastly different informational age, we must identify group needs and desires when we reach back into the roots and origins of how once unbelievably extreme views have now gained acceptance and legitimization by a party in power. My godmother’s family’s needs were rooted in their Christian sect in Syria, and any alternative to the criminal regime of the Assad regime posed an existential threat to their population. While this argument has merit in Syria, it allowed them to justify or dismiss diabolically criminal actions. As a result, conspiracies became more comforting as a logical answer to criticisms to my godmother’s family and the elder men that Thanksgiving weekend.

The right-wing base – a combination of nationalists and evangelicals (also akin to the orthodox church and nationalists behind Putin in Russia) – in the U.S. has similarly embraced wholly irrational conspiracies in order to defend Trump. We need to carefully identify the origins and symptoms of the dangers of autocratic praise and the blinding biases of those in support, and explore the greater context that helps harbor them. If we become increasingly unwilling to expand beyond the confines of sources of information that comfort beliefs and insecurities, and neglect the greater context of the issues in our communities, then the most basic realities will become increasingly obscure and difficult to discern.

Leave a Reply