From Electology:

“And the award goes to …”

The camera pans in on your favorite celebrity’s face as the host readies the result. You wait …. With all the fanfare, it’’s hard to deny that award ceremonies can get pretty exciting.

The camera pans in on your favorite celebrity’s face as the host readies the result. You wait …. With all the fanfare, it’’s hard to deny that award ceremonies can get pretty exciting.

These awards also have an impact. They translate into increased sales, pay bonuses, and more lucrative contracts. For actors, it can determine the next movie they star in. And for lifetime awards, these ceremonies can be deeply emotional for the candidates.

But what if these awards weren’t meaningful at all? What if the voting methods these award ceremonies used were so poor that we can’t know if they regularly snub the truly best candidates?

Unfortunately, terrible voting methods are just what we see.

Let’s start with the Grammy’s. This year, there was controversy when Beck beat out Beyonce for album of the year. The folks at Vox did a nice job identifying the issue here. Beck’s supporters were less divided whereas Sam Smith, Pharrell, and Ed Sheeran had overlapping bases of support with Beyonce. This could have been what cost Beyonce the award. Vox even offered some evidence for this by pointing out Beyonce’s higher Metacritic score over Beck’s. Note that because Metacritic scores use a score-based system, it’s more resistant to this “dividing”.

This “dividing” is what we call vote splitting. The Grammy’s uses a voting method where voters are limited to choosing one candidate (plurality voting). Because voters can’t say anything about the many candidates they’re interested in, the votes split among similar candidates. A less divided candidate—even if less popular—can pull into the lead with an undeserved win.

This “dividing” is what we call vote splitting. The Grammy’s uses a voting method where voters are limited to choosing one candidate (plurality voting). Because voters can’t say anything about the many candidates they’re interested in, the votes split among similar candidates. A less divided candidate—even if less popular—can pull into the lead with an undeserved win.

This doesn’t mean that you—or Kanye West for that matter—should be angry at Beck. Beck didn’t choose the Grammy’s voting method, and he surely worked hard to make his album. If you want to blame someone, blame the Grammy’s for choosing a bad voting method.

And there’s the Oscars. This year the Oscars chose Birdman for best picture. Birdman is about an actor played by Michael Keaton who attempts to reclaim his reputation as he opens up a Broadway play. But did Birdman deserve to win?

The Oscars used a voting method called instant runoff voting, a ranking method that uses a series of eliminations. It looks at ballots’ rankings from round to round. Unfortunately, the method also ignores ballot information and is susceptible to vote splitting in its own unique way. It does not—as the folks at fivethirtyeight wrongly concluded—ensure winners with broad-based or even core-based support.

As mentioned before, score-based systems avoid many of the issues associated with a choose-one method. That’s because you can express support for multiple similar candidates. But score-based methods also avoid issues associated with instant runoff voting. For an alternative evaluation that uses a score-based process, consider the ratings from Internet Movie Database:

As mentioned before, score-based systems avoid many of the issues associated with a choose-one method. That’s because you can express support for multiple similar candidates. But score-based methods also avoid issues associated with instant runoff voting. For an alternative evaluation that uses a score-based process, consider the ratings from Internet Movie Database:

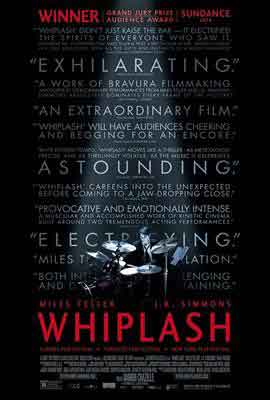

- Whiplash: 8.6

- Boyhood: 8.2

- The Imitation Game: 8.2

- The Grand Budapest Hotel: 8.1

- Birdman: 8.1

- The Theory of Everything: 7.8

- Selma: 7.6

- American Sniper: 7.5

Suddenly, Whiplash seems like a better candidate than Birdman.

Fortunately, the Oscars doesn’t always get their voting method wrong. For instance, they do use a score-based proportional method to determine the nominees for Best Visual Effects. So good for them, there!

Readers here will see us go back and forth a bit in recommending score voting (when you score candidates on a scale and the candidate with the highest score wins) and approval voting (where you choose as many candidates as you want and the candidate chosen the most wins). On average, score voting performs a bit better, but that doesn’t always make it a good pick.

For instance, we recommended approval voting for the Baseball Hall of Fame. There, voters had over 35 candidates on the ballot. That’s a lot of candidates to score, but it’s not a big deal with approval voting. Additionally, there were over 500 voters.

A large sample of voters or judges helps with what we call “random error,” which is the inexactness inherent in any measurement. But when you have fewer voters (or judges), you want a voting method that has greater sensitivity in its measurement—like score voting. That will reduce some of that annoying random error.

Awards ceremonies can be exciting. But the next time you hear the words, “And the award goes to … “ be sure to think about the voting method. Because an award that doesn’t intelligently consider how its winner is chosen isn’t much of an award at all.

Leave a Reply