This is part one of a series on Cameroon’s current crisis:

“We are thus faced with a situation in which Third World States, themselves the pre-beneficiaries of resolution 1514 (XV) guaranteeing the principle of self-determination of all peoples, become modern colonizers of less fortunate peoples within their area.”

– Judge TO Elias, President of the International Court of Justice (as he then was), in ‘The Role of the ICJ in Africa’, 1 RADIC, 1989, p.8

Over the last four months, the English speaking Regions of the North West (NW) and South West (SW) in the West African State that styles itself as the Republic of Cameroon have been the grounds of protracted protests. Prompted by strikes by lawyers of the Common Law extraction and by Anglophone[1] teachers, people from different walks of life in the Anglophone community have expressed dissatisfaction with the poor treatment Anglophones have been subjected to in a Francophone dominated Cameroon.

In the face of what has been interpreted by many observers as deceit in negotiations and preference for repression by the 34 year old regime in place, Anglophones have adopted weekly ghost towns since 09 January 2017 as a call to order to the Government and a show of disapproval of Government’s fascist and barbaric repression. Such repression has involved intimidation, verbal violence, unnecessary and disproportionate use of force, arbitrary and illegal detentions on trumped up charges in pure disrespect of due process, summary killings, internet shut down for the community concerned, muzzling of the press and some of the worst crimes against humanity.

To show how serious they are, the vast majority of the parents have kept their children at home amidst Government’s calls for return to school without the striking teachers having lifted their strike action in an acceptable manner. What this situation has rehashed in several circles is the question of whether there is an “Anglophone problem” in Cameroon.

Background: black on black annexation in three stages characterized by deceit

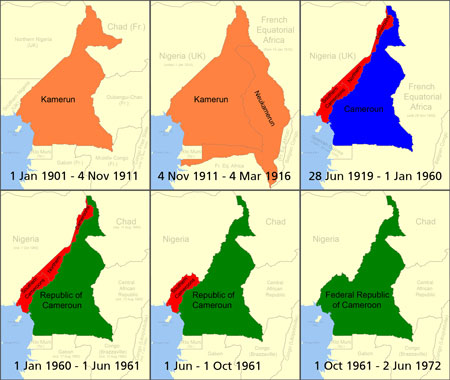

The roots of this crisis can be traced back to Cameroon’s colonial past. During the scramble and partition of Africa Germany annexed for herself a Protectorate (Kamerun Schutzgebiet) in mittel-Afrika by signing a Treaty of Protection on 12 July 1884 with the Kings and Chiefs of Duala, an area found around the estuary of the River Wouri. Following the hinterland theory adopted at the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 Germany brought under her control a territory that extended from this estuary to Lake Chad. By 1912 German Kamerun had taken shape with clear international boundaries established by boundary treaties with neighboring colonial powers. Two years later in 1914 the First World War (WWI) broke out and France and Britain decided to attack Germany everywhere, including in her colonies in Africa.

Germany was defeated in Kamerun in 1916 by a joint Anglo-French effort. The two powers then established a condominium. This condominium was short-lived partly because of the clear cultural differences between Britain and France.

The 1916 Simon-Milner line split Kamerun into two parts, one for each of the allied powers. As such, French Cameroon (FC) with a total land mass of 431000km² and British Cameroons with total surface area 86000km², became two distinct colonial territories equal in status. Following the colonial dynamics at the time none of these two colonies, as already mentioned equal in status in international law, could claim paternalism over the other. When the League of Nations (LON) was created on 10 January 1920, it established its mandate system in 1922 under which all former German colonies were placed.

Due to lack of resources the LON gave the administration of these colonies especially to European powers and recognized any boundary treaties they established on them. Therefore, the Order in Council of 26 June 1923 by which the British split their own share of German Karmerun into British Northern Cameroons (BNC) and British Southern Cameroons (BSC) was an act of creation of two distinct territories. For several years these two territories where administered from the British Colony of Nigeria. However, in 1954, BSC gained her autonomy. When the LON was transformed into the United Nations Organisations (UNO or simply United Nations, UN) after the Second World War (WWII), the LON mandate system was also transformed into a trusteeship system in 1945. The UN then embarked on the unconditional decolonisation of the trust territories.

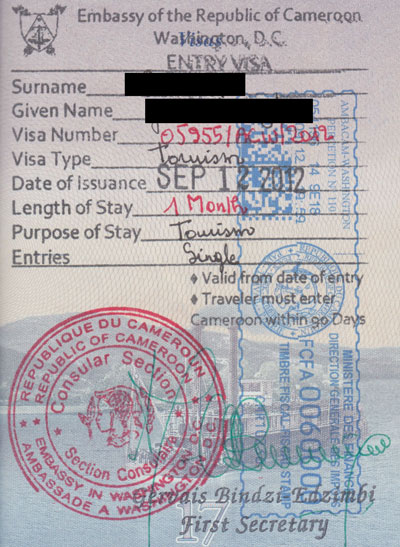

The UN gave unconditional independence to FC on 01 January 1960. She then took the name Republic of Cameroun,[2] or La République du Cameroun (LRC) in French. However, seen their taste and love for French domination over their own people, the French handpicked native political class in the business of Government in FC had signed the 1959 secret cooperation accords with France[3] to enslave their people indefinitely. Independence for FC has therefore been only on paper for two regimes that have governed LRC since 1960. The current state of affairs shows that these elites have clearly privileged the respect of these accords over the principles of independence enshrined in the UN Charter. A glaring proof is the use of the French minted Franc CFA today.

The story will be different and far more painful for BSC. This is because the UN literarily sold-off BSC into annexation to LRC. LRC has since then subjugated BSC nationals to double enslavement; first under them and second has dragged BSC into French subjugation, usurping all BSC resources for the almost exclusive benefit of Francophones and of France. To understand this, one must see how BSC fell under LRC control through three acts of annexation that have led to more than 55 years of pain that define the Anglophone problem.

In effect, today’s Republic of Cameroon is a merger of two independent States in 1961. The union was originally intended to be a loose association. However, events show that the union between these States, one of them LRC and the other BSC, was hasty and poorly negotiated.[4] The unfolding of events since this badly begun process may clarify why LRC has literarily annexed and dominated BSC for over 55 years and shed more light on why Anglophones feel the way they do about LRC as seen in the protracted and violent nature of the protests.

Far too many experts have said emphatically that the UN violated UN Charter Article 76(b)[5] and UN Resolution 1514 (XV) of 14 December 1960[6] when she organised a plebiscite on 11 February 1961 to condition the independence of BSC with “joining” either LRC or the Federal Republic of Nigeria (FRN).[7] It is therefore not surprising that the pretext that BSC was not economically viable[8] used to justify this plebiscite has been treated by these scholars as intellectual dishonesty and a ploy to hide secret agendas between the superpowers concerned. This is certainly the case as simple common sense will tell anyone that in self-determination it is the people who determine their future and not the condition of their territory at any one point in time that imposes a future on them. A piece of land cannot have powers over human beings.

Nevertheless, the people of BSC voted in this plebiscite in favour of “achieving their independence by joining LRC.” It should be noted that by now LRC had become independent from France on 01 January 1960 and accepted as a member of the UN through UN Resolution 1476 (XV) of 20 September 1960 and was therefore bound by all UN Laws and Resolutions. UN Resolution 1608 (XV) of 21 April 1961 called for an international conference in which the terms of the union between LRC and BSC and the “joining by association”[9] proposed by the UN will be negotiated on equal terms and a Treaty of Union signed and deposited at the UN Secretariat[10] to ascertain the constitution of a new State. This conference was never organised, naturally so because LRC had voted against UN Resolution 1608(XV). In its stead, LRC modified her Constitution into a Federal one and imposed it on the BSC delegation at the Foumban Constitutional Conference (FCC) of 17-21 July 1961.[11]

The compliance of John Ngu Foncha, Permier of BSC, with this unlawful FCC raises concerns as to whether he had entered secret pacts with Ahidjo to sell-off BSC nationals to LRC. Whatever the case, the CoFRC was a modification of the Constitution of LRC of 04 March 1960 void of any backing by a Treaty of Union and ratified only by LRC Parliament. It is therefore clear that its entry into force in BSC territory on 01 October 1961 consecrated a secret union tantamount to a violation of UN Charter Article 102 (1&2) and an act of annexation of BSC. This fact of annexation of BSC by LRC is further evidenced by the promulgation CoFRC into law on 01 September 1961 by Ahmadou Ahidjo, first President of LRC, without waiting for the independence of BSC on 01 October 1961 and without providing a Treaty of Union to the UN.

Under UN Resolution 1608(XV) it was expected that the union of the two States to create a new State, in the spirit of UN Resolution 1350 (XIII) to be styled Federal United Republic of Cameroon, would have led to an application for membership for this new entity. We emphasise that like the non-establishment of the Treaty of Union, the Federal Republic of Cameroon never applied for UN membership. As such considering the prevailing of UN Resolution 1476 (XV) as membership document for what is today’s LRC, BSC can be seen to be under UN endorsed annexation by LRC.

Despite all this non-respect of procedures and the breaking of laws, the Federal Republic of Cameroon (FRC), with a Constitution that was illegal ab initio, took shape on 01 September 1961, not 01 October 1961, and pretended to exist for 10 years. The promulgation of CoFRC on 01 September 1961 without its adoption by BSC parliament is another pointer to the illegality of the document in BSC territory.

Nevertheless, the wheel of illegality kept spinning as a weak and consenting John Ngu Foncha allowed the takeover of BSC territory by LRC. Under CoFRC, LRC transformed herself into East Cameroon then baptised BSC as West Cameroon. The new flag bore two stars representing the two federated States. Article 47 CoFRC forbade any bill, action or proposal that could “impair the unity and integrity of the Federation”. Even so, Ahidjo abolished the FRC through a unilaterally proposed referendum in May 1972.

To make sure that he achieved his aims under his One-Party State, his illegal referendum of 20 May 1972 had ballot papers with only two answers that meant the same thing; “OUI” and “YES”. A former Government Minister has refuted this claim stating that there were other ballot papers that had the “NO” and “NON” option but that these ballot papers were printed in far lesser amount than the “OUI” and “YES” ballot paper. He justified this irregularity with the flimsy logic of the Ahidjo establishment at the time that reasoned out that, “…whatever the case, the “YES” and “OUI” would still…[win], since the people of East Cameroon would normally…[prefer it]”.[12]

This fact only further reinforces the thesis of a clearly irregular referendum and shows why with no campaigning going on and with the incorrect organisation of the fake referendum on the whole territory, Ahidjo’s “OUI” and “YES” jointly obtained the shameful and grossly-exaggerated 99.9% of the votes cast.[13] As such, Ahidjo had taken the second step on the path to full annexation and annihilation of BSC by LRC. This referendum is even more repugnant when one considers that it was a birthday gift to Ahidjo’s wife, Germaine born on 20 May 1932.[14]

Ahidjo’s new republic was styled the United Republic of Cameroon (URC). It was to be a bicultural country notably through bilingualism and the preservation of the legal and education systems of BSC and LRC.[15] However, the identity crisis of the people of BSC that had begun from the ill-negotiated union of 1961 was to be further aggravated by this betrayal by Ahidjo. In 1982, Ahidjo resigned and was succeeded by his handpicked successor, Paul Biya. On 04 February 1984, Paul Biya signed decree No 001 to rename URC as LRC. Therefore, the official name of Cameroon today is the exact name FC had at her independence on 01 January 1960.

This decree was the third and final act for BSC annexation. It has however not been taken as a complete fatality as many have seen it as the restoration law of BSC. Proponents of this idea argue that by returning to the name LRC meant that LRC as one of the parties to the 1961 pacts had effectively left the already controversial union and by that pact the LRC administration in BSC was now clearly by force. Biya’s decree also showed that LRC of 01 January 1960 that had become a member of the UN on 20 September 1960 without BSC was bent on annexing BSC, contrary to UN Resolutions 224(III) of November 1948 and 2625 (XXV) of 24 October 1970 that forbade the absorption of Southern Cameroons. The continued recognition of Cameroon under UN Resolution 1476 (XV) can be taken to mean that the UN has endorsed this annexation.

From the foregoing it is unarguable that there are two linguistic, cultural and national identities in what is known as Cameroon today. For the purpose of identifying them, the term “Anglophone” should be taken to refer to an individual whose origin is from or who is a native of BSC and a “Francophone” a native of LRC of 01 January 1960 that remerged on 04 February 1984. The decree of 04 February 1984 set the final groundwork for the “Anglophone Problem” in Cameroon.

The people of BSC or West Cameroon (1961 to 1972) have had no autonomous government since 20 May 1972. From 04 February 1984 what is left for them within LRC as the major facets of their cultural identity are their education and legal systems. Since 1972 they have lost what little sovereignty they had left over their territory. Therefore, all their resources have been syphoned and used elsewhere, all in the name of unity. This is in violation to UN Resolution 1803 (XVII) of 14 December 1962.

For several years the petroleum deposits in Victoria, baptised by Biya as Limbe, and elsewhere in the Ndian, have provided more than 60 per cent of the State budget while the Cameroon Development Corporation (CDC) and PAMOL plantations continue to be a source of foreign currency. Paradoxically, BSC has had very little infrastructural development. Also, Anglophones are side-lined in Government as they are very certain that they can never hold certain ministerial positions not to talk of the position of Head of State.

After the fake referendum of 1972, Ahidjo split BSC into North West and South West Provinces, later Regions under Biya. Since then, most of the appointed administrators to those regions are Francophones. This is another grave source of malaise as people who were groomed in the ways of democracy are now forced to obey unelected officials who are not local inhabitants of their constituencies.

The National Refinery Company, with French acronym SONARA, found in Victoria has never had an Anglophone or BSC native as Director General. English has been relegated to the background in official documents and presidential speeches. Where English appears in official documents it is treated as a “translation” and the characters chosen show that it is a language subservient to the French language.

Even the currency, the Franc CFA, a perpetuation of French colonial rule, has no single word in English on it today. The General Certificate of Education (GCE) Board was created only after Anglophone blood had been spilled and since its creation in 1993 it has been under attack. Not succeeding to abolish it, successive Francophone Ministers of Education have instead started appointing Francophone teachers to the English sub-system of Education. The Minister of Higher Education made a very disturbing statement in this regard in December 2015. He declared that sending anyone, irrespective of his educational background, to teach in any sub-system of Education is constitutional. The majority of these Francophone teachers sent to the English sub-system of education have no mastery of the GCE system and little or no fluency in the English language.

All this was done in the name of national unity and integration and something called “harmonisation”. These Francophone teachers teach in broken English and therefore in respect of the “constitutional right to teach anywhere”, LRC has institutionalised the under-education of Anglophones. The Anglo-Saxon universities of Bamenda and Buea have also been flooded with Francophone lecturers and the majority of students admitted in the higher institutes of learning of these universities are Francophones.

From the nature of affairs, the Francophone-led Governments of Ahidjo and Biya may likely have decided that Anglophones will never have control over scientific and technical education in their community. This is because the Office du Baccalaureat that manages the francophone sub-system of education controls the science and technology branch of education everywhere in the country including in the NW and SW. As such, during exams, a francophone who sets a question containing the phrase “…bougie du moteur” translates it directly as “…the candle of the engine”, instead of the “…engine spark plug”. That says it all. In the legal system, successive Francophone Minsters of Justice have made sure to appoint mainly Francophone judges to the NW and SW. These Francophone judges have eroded the English Common Law system. In a way, Anglophones are being systematically marginalised and assimilated.

In the early 1990s the All Anglophone Conferences (AAC) I (1993) and AACII (1994) had attempted to call the attention of the Government to all these annexation, marginalisation and assimilation issues that define the Anglophone problem. These Conferences asked for a return to Federalism as the best way to preserve bi-culturalism and foster unity. However, the Government did not heed.

The Southern Cameroon National Council (SCNC) was formed after AACII to push for this Federalism through dialogue with the Government. However the Biya regiome treated “Federalism” as “secession” and the SCNC as a “secessionist group”. This radicalised the SCNC that now openly calls for separation (not secession).[16] More Anglophone groups calling for either a Federation or separation have risen but the Government of LRC has treated them like she does the SCNC. Members of such groups and school of thought continue to be imprisoned and tortured. Many of these groups have now taken the Government of LRC to international jurisdictions and there are incessant appeals for the UN to intervene to resolve the BSC or Anglophone problem in LRC.

Sources

[1] The terms Anglophone, West Cameroon, British Southern Cameroons (BSC) may, depending on the idea expressed be used interchangeably in this article.

[2] Notice the spelling with a “u”. That is exactly how it is spelled in UN Resolution 1476 (XV).

[3] Daily News Cameroon, “Shocking cooperation agreements between [LRC] and France 57 years ago”, consulted on 01 February 2017 from https://goo.gl/iuOhLv

[4] Ayim, M., A., (2010), Former British Southern Cameroons Journey Towards Complete Decolonization, Independence and Sovereignty, Author House, Bloomington, USA.

[5] Southern Cameroons Youth League, (n.d), “In the matter of Europe vs Cameroun. Resolution by the European parliament: the human rights enquiry.” consulted on 10 January 2017 from https://goo.gl/9tBM1m. cf. p.2.

[6] COMDESC, (n.d), “The Re-colonisation of the former United Nations Trust Territory of the Southern British Cameroons”, Briefing paper, consulted on 10 January 2016 from https://goo.gl/1tsDkA, cf p.10.

[7] Bamenda Provincial Episcopal Conference [BAPEC], (2016, December 22), “Memorandum presented to the Head of State, his Excellency President Paul Biya, by the Bishops of the Ecclesiastical Province of Bamenda on the current situation of unrest in the Northwest and Southwest Regions of Cameroon” p.2.

[8] Ayim, M. A., (2010), op. cit. p.118.

[9] COMDESC, (n.d), op. cit. p.9. (Also see Principle VII of United Nations General Assembly Resolution 1541(XV) of 15 December 1960 on Association of States.)

[10] Unrepresented Peoples and Nations Organisation (UNPO), (2005, October 25), “Southern Cameroon: Celebrating United Nations Day”, consulted on 8 January 2016 from https://unpo.org/article/3126.

[11] Achankeng, F., (2015), “The Foumban “Constitutional” Talks and Prior Intentions of Negotiating: A Historico-Theoretical Analysis of a False Negotiation and the Ramifications for Political Developments in

Cameroon”, in Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective, Article 1, Volume 9, Number 2 Negotiation: Dispute Resolution and Conflict Management in Nigeria and Cameroon.

[12] Spectrum Television (STV) Cameroon, Entretien Avec..program of 14 January 2017

[13] Wikipedia, “Cameroonian Constitutional referendum, 1972” consulted on 31 January 2017 from https://goo.gl/H1e6BW

[14] The Guardian Post Newspaper “Stark evidence of Anglophone marginalisation”, No 0109 of Monday 17-23 May 2004

[15] See the Constitution of the United Republic of Cameroon of 02 June 1972.

[16] “In international law, such as that governing members states of the African Union, secession is the detachment of a territory (B) that was part of another (A) at the date of A’s independence. On the contrary, separation is the detachment of a territory (B) that was not part of Country (A) at the date of A’s independence. In this respect, because Southern Cameroons was not part of French Cameroun when it was granted independence by the United Nations in 1960, it’s detachment is not “secession” but separation. While generally secession is not legal under the African Union Constitutive Act (Charter), separation is permissible.” (https://goo.gl/05AK8d)

David Anderson, J.D. NY says

Excellent article. The Cameroonian mess will be more in the new soon I think.

Well done.

David Anderson