Poet Nora May French’s Account of Her 1907 Abortion Is an Infuriating Read—and a Sobering Reminder of What History Omits.

I am no longer able to think of Carmel without thinking of abortion and Nora May French.

For this new habit of mind, I blame two things: the U.S. Supreme Court, and the literary scholar Catherine Prendergast’s searing 2021 masterpiece, The Gilded Edge: Two Audacious Women and the Cyanide Love Triangle That Shook America.

From visiting Carmel, I had heard all about Carmel’s early 20th-century history as a colony of artists and bohemians. But I had never heard of the poet French, or understood how much the popular history of Carmel left out—until I picked up Prendergast’s book, which defies categorization. It’s a head-spinning history, a maddening mystery, and a bracingly timely reminder of how easy it is to erase the aspirations and accomplishments of women, even in avant garde Northern California.

The Gilded Edge begins with French’s own real-time account of her own 1907 abortion. This description, discovered by Prendergast in the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, was hard to read last fall, when I first encountered it. It is infuriating to read now, weeks after the U.S. Supreme Court canceled the constitutional right to abortion. Someone really ought to put the text on a neon billboard outside Justice Samuel Alito’s bedroom window.

French, a brilliant 25-year-old poet, “could not afford a ‘therapeutic’ abortion in a hospital even if she could convince a doctor to give her one,” Prendergast writes. So, the poet induced an abortion by swallowing pills she’d bought at a local drugstore in San Francisco. Such abortifacients, advertised in newspapers as safe and reliable, came in colored boxes with names like “Dr. Conte’s Female Pills,” and “Dr. Trousseau’s Celebrated Female Cure.” They also contained dangerous chemicals, like turpentine.

French recounts swallowing pills on a Saturday morning, and feeling nothing. The following day, she is awakened by a contraction, and then waves of spasms, nausea, and intense pain.

French had moved to San Francisco the year before, months after the earthquake, and was already succeeding as a poet and writer—winning a newspaper’s poetry contest and being published in literary journals. But if she had the baby (she had become pregnant by her married boyfriend Harry Lafler, a literary journal editor), she knew she was risking her burgeoning career, and could end up raising a child alone.

Between contractions, French wrote to Lafler. “Very dear, I have been through deep waters, and proved myself cowardly after all.” “I have gone through every shade of emotion… It was as if we were walking together and my feet were struggling with some pulling quicksand under the grass. I would come near screaming very often.

“Motherhood! What an unspeakably huge thing for all my fluttering butterflies to drown in! A still pool, holding the sky.” “I looked into it day after day, and sometimes I could see the sky, and sometimes only my drowned butterflies. Oh—”

That is where the letter cuts off.

——————————————————————————————————————-

At the end of our own Gilded Age, and the beginning of the post-Roe era, this story speaks all too loudly. It’s about the human horrors of letting judges, or anyone else, determine our rights on the basis of history—especially when history omits so much.

——————————————————————————————————————-

French did survive her abortion, and soon after relocated to Carmel, where she took up residence in the guest cottage of a married Bay Area couple with many literary friends, Carrie and George Sterling.

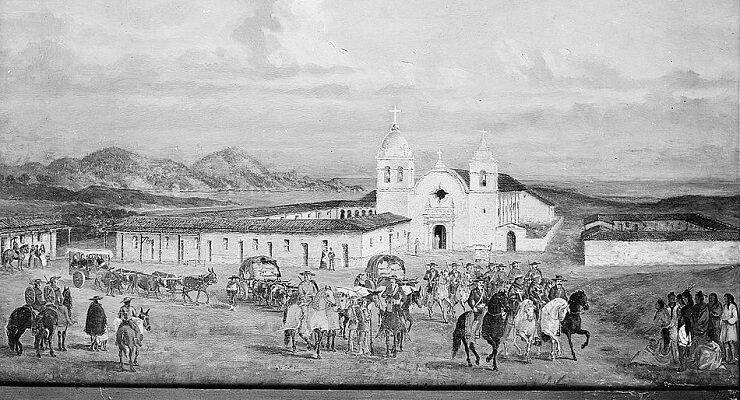

George Sterling styled himself as a writer (championed by Ambrose Bierce) and was a prominent member of the Bohemian Club, a famously elite male social institution with an artistic bent, and founded in 1872. But Sterling’s real business was real estate. He used his literary network to attract artists and writers to Carmel—among them Jack London and Upton Sinclair—to give the place a creative cachet that would help Carmel Development Company sell land. Prendergast shows that Sterling spent more time philandering and drinking than writing. Carrie Sterling did most of the recruitment work.

In Carmel, many bohemian men pursued the beautiful and talented French, plying her with writerly advice while seeking to co-opt her talent. George and Nora became lovers. Then, less than a year after her abortion and move to Carmel, Nora French died of cyanide poisoning. George Sterling was away. Carrie Sterling found her body. What actually happened remains a mystery.

The death of the young and pretty poet made news nationwide (“Midnight Lure of Death Leads Poetess to the Grave,” one headline crowed) and inspired copycat suicides. In the years to come, Carrie and George Sterling split up; each would later commit suicide, by cyanide. Others connected to the Carmel colony met unfortunate ends, too.

The saga took place in an era when people talked of the “New Woman” enjoying more rights and possibilities, Prendergast notes. But the reality was different, as the stories of Carrie Sterling and Nora May French demonstrate.

“Carmel was a roiling pot of exploitation. Women’s horizons were limited by the identities the men assigned them, namely scorned wife and elusive muse,” Prendergast writes. “Even when men claimed to want women who were more sexually liberated or allowed to work outside the home, all the negative consequences of the flowering of liberation were women’s alone to bear.”

The indignities these women suffered didn’t end with their deaths. Nora May French and Carrie Sterling were largely left out of the mythology of Carmel. The lecherous George Sterling, whose poetry is hackery, is still remembered as the great Bohemian writer who helped make Carmel the place it is today. (He even has a park named after him in San Francisco.)

There is no archive of French’s papers, Prendergast writes. She located French’s letter, describing her abortion, among Lafler’s records. “Wouldn’t it be nice, I think, to see it amid a collection of other letters testifying to the length of women’s struggle for reproductive freedom, rather than among the papers of an abusive ex-boyfriend?” the author asks in the book.

Today, at the end of our own Gilded Age, and the beginning of the post-Roe era, this story speaks all too loudly. The lesson is about more than abortion or discrimination. It’s about the human horrors of letting judges, or anyone else, determine our rights on the basis of history—especially when history omits so much.

This article appears in Zócalo Public Square.

Leave a Reply