With China economy ablaze, growth continues and population pressures mount so David Watts takes a look at a rising world power in midst vast internal change

Dragon economy ablaze but democracy lacks bite

Author: ankur

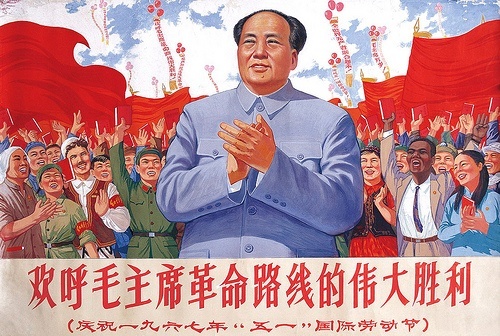

China is preparing to endorse new leader Xi Jinping this autumn. Overcoming some of the world’s most traumatic events in modern times — the Cultural Revolution, the Great Leap Forward and the 100 Flowers land reform which added to an already monstrous total of deaths through famine — there has never been a better time to be a Chinese as the country’s economy powers ahead and Beijing occupies an increasingly important place on the world stage.

But as the nation prepares to endorse a new leader in Xi Jinping at the party conference this autumn, where is the country going and what are its ambitions for the future?

At first blush it would appear that Beijing is intent on trying to match US power as it challenges American military might and influence in Asia and fences with Washington’s allies over the control of islands and oil resources in the South China Sea, while at the same time maintaining its holdings of increasingly valueless US dollar bonds.

From the outside, China appears to be a unified monolith led by the world’s largest political organization, the Chinese Communist Party, but the reality is much more prosaic and fragmented, according to the former newspaper editor and China expert, Jonathan Fenby. The phalanx of China cheerleaders, including George Soros and Francis Fukuyama, who laud the country for its disinterested civil servants who run it in the overall interests of its 1.2 billion citizens, are seeing only one side of a complex and contradictory picture, he says.

So as the new central committee takes shape and prepares to run the country, we are witnessing the continuation of a linear policy set in motion by the late Deng Xiaoping in 1978, which set the nation on the path to prosperity through his dictum: ‘Poverty is not socialism. To be rich is glorious.’

But merely getting rich was not the principal aim of the diminutive helmsman. He saw the economy as a means not only to make China great again, after the depredations of the Mao era, but also to maintain the power of the communist party after the Great Helmsman had brought about its almost total destruction. The bottom line both then and now was the maintenance of the power of the party at all costs.

The result is what we see today: China as the workshop of the world in the way that Britain was at the time of the Industrial Revolution. The Shenzhen region bordering Hong Kong is now responsible for the making of an extraordinary 5 per cent of the world’s total manufactures. Its spectacular rise has mirrored that of China as a whole, and its story is one that foreigners are familiar with.

Not so Yiwu in Zhejiang province, which bills itself as the world’s small manufactures capital. It features 80 towers with small firms turning out ‘everything small that is made in the world’, according to Fenby when he spoke at the Royal Institute of International Affairs, Chatham House. Here you will find prayer beads for Mecca, sombreros for Mexico and string bikinis for Brazil. It is far from the big metropolitan centres of Beijing and Shanghai and a place well off the tourist track — indeed off anyone’s track, unless they are there to buy any of the 20,000 product ranges that will be on offer when current expansion plans are brought to fruition. Everything is on offer from British royal jubilee souvenirs to nick-knacks to be offered in a million shops worldwide — all made to order and on paper-thin profit margins by workers, many from rural areas, working to hours and productivity demands that would constitute slave labour anywhere else.

This is exactly the kind of phenomenon that Deng had envisioned when he realized the combined potential of China’s cheap labour and the cheap capital which Chairman Mao’s inward-looking policies had kept locked up inside China. But first he had to open China to the outside world to gain access to markets that would make the country grow rich until it was able to develop its own domestic markets as a factor in the national economy’s wealth-creation. Even today the nation’s domestic market does not create enough demand to keep the national economic engine purring.

But even Deng would probably have been surprised at the world of superlatives that China now inhabits, with its inhabitants smoking 30 per cent of the world’s cigarettes, eating 55 per cent of its pigs — the average urban Chinese eats the equivalent of one pig a year — while maintaining the world’s biggest standing army with more than two million troops.

And in spite of the occasional explosion into headlines of anti-government protests in China, we see the party maintaining its power in spite of the increased wealth of the citizens and an increasing number of protests against instances of corruption and inappropriate use of power by local authority figures. The number of protests now runs at an annual figure of about 150,000. That seems a large figure even for a country the size of China but it does not translate into substantial demands for democracy. The protests are largely confined to local areas and concern local issues. China is a nation of localities: everything from beer to motorcycles is made and consumed locally in the regions.

For the most part, the populace seems to have absorbed the authorities’ lessons of the Tiananmen Square incident of 1989 — any attempt to destroy the power of the communist party will be met with the utmost force. That is not to say that the authorities will not increasingly have to face levels of dissatisfaction, especially through social media, which it is having great difficulty in containing without the crude censorship measure of actually shutting down individual sites.

The ruthless, bigger, faster, better route to development that the government is pursuing will continue to prompt protests from ordinary people concerned about environmental degradation and rising prices, both of which are a by-product of head-long urban expansion and industrial development — China has 20 per cent of the world’s population on some 9 per cent of the globe’s arable land. The price of vital vegetables is being forced up as urban sprawl eats into farmers’ land — one Chinese city has lost 25 per cent of its vegetable growing terrain in the last few years.

These and other population pressures are forcing the authorities to look at how to deal with this expanding problem and one theory emerging from French academia is that this is one of the key drivers of China’s move into Africa. According to this theory, apparently supported by a senior scientist, the authorities believe that the Chinese mainland cannot support more than 700 million people and that ways must be found to have some 300-500 million find other accommodation. Chinese moving abroad to better themselves is not a new phenomenon and they are to be found all over the world in every conceivable activity; but the theory of French authors Serge Michel and Michel Beuret makes for a new twist on this fascinating saga, which will be followed with interest.

Income disparities have now reached all-time highs and have become so controversial that the government no longer publishes them. But all of this dissatisfaction does not appear to amount to any great desire for democracy — there are no internal forces of any size demanding it — a phenomenon which China has never experienced, having seen its only democratically-elected prime minister, Song Jiaoren, assassinated on Shanghai railway station in 1913 before he could take office.

The American administration has pinned its hopes for the democratization of China over the years on the emergence of a middle class — the phenomenon which has spawned democracy all over the world. So far China has proved the exception to this rule.

But then the average middle-class Shanghai worker has no incentive to share the fruits of his labour — two cars, a nice flat and private education and health care — with anyone else. ‘The last thing he would want would be for 700m peasants to have the vote.’

And that is why the Chinese property market has developed in the way that it has: with prices kept buoyant to maintain values in spite of massive over-supply in some areas. All protests which threaten to destroy those values are quashed at the government’s behest. Deng would have been proud.

Article Source: articles base

About the Author

Ankur choudhary is working with rubicon publicer pvt.ltd (https://asianaffairs.in). Asianaffaris.in publish news and articles from all over the world, Islamic country news, Pakistan news, Articles on current affairs, world affairs.

Chen and the art of free expression

Author: ankur

SILENCED: Hundreds gathered to pay tribute to courageous journalist Marie Colvin, who was killed in Syria

The church of St Martin in the Fields in Trafalgar Square was packed with people from all walks of London life for a remembrance service.

Many of them had probably not seen the inside of a church for a long time and though most were journalists, many were no more than readers of the work of the writer in whose memory hundreds had gathered to pay tribute.

The subject of their admiration, Marie Colvin of The Sunday Times, was only the most high profile of a lengthening role call of media workers who now pursue one of the world’s most dangerous professions. She paid with her life for her determination to tell the stories of the victims of President Bashar al-Assad’s blood-soaked regime in Syria.

With governments taking ever more control over the lives of ordinary people and the supply of information to citizens, it has never been more important for independent and courageous investigation by journalists to bring out information that would otherwise remain hidden, to the detriment of the interests of the citizen, good government, democracy and the fight against corruption everywhere.

Nowhere has this become more important than in China, where the media are playing an increasingly vital role in the citizens’ attempts to bring their rulers to account in the absence of any semblance of democracy and an increasingly corrupt ruling clique.

In the most visible example of this it can even be argued that media pressure — often in the form of blogging by private citizens — has had the effect of compelling China and the United States to reach a settlement over the case of the blind dissident Chen Guangcheng.

The details of Chen’s valiant struggle against the imposition of China’s sterilization policy would not have become widely known in China and abroad were it not for the activities of bloggers who passed on their knowledge to the outside world and alerted activists in the US and elsewhere to his plight.

The blind Chen educated himself as a lawyer in order to help people in his rural community of Linyi obtain redress for abuses by local government officials responsible for implementing the sterilization policy.

In one case, a 59-year-old man was taken hostage because the authorities could not find his daughter who was due for sterilization. ‘At about six o’clock in the afternoon he was found unconscious by the side of the Yuncai bridge. His relatives found out that he had been held by family planning officials for a whole day and tortured and starved. Then they asked him to go and look for his daughter. He asked for food but was refused.’

In the afternoon a female official smelling of alcohol beat two elderly people of about 70 years old, then took the 59-year-old man to the courtyard where she beat him with brooms, breaking three of them.

At about five o’clock she pushed him into a small room, told him to sit on the cold cement floor and unbend his legs. She took the lead stamping on them.

Apparently the family planning programme is managed in much the same way across the rest of the country, with relatives suffering appalling mistreatment if women avoid sterilization. Euphemistically named Family Planning Learning Centres are used to detain people under miserable conditions in the name of re-education — at their own expense.

No wonder Chen’s cause has been taken up across the world.

After months of being held prisoner in his own home with his family, thugs on guard twenty-four hours a day, Chen somehow managed to escape and find his way to the American Embassy in Beijing. And it is here that the story begins to get complicated: obviously he could not have done so without help from individuals high up in the government.

First he had to penetrate the wall of guards fencing him in and then he had to have transport to Beijing, avoiding any checks that might be in place. None of this could he have done on his own, being blind and as one of the most wanted men in the country.

So the execution of Chen’s escape points to a difference of opinion between political factions in the capital: someone trying to discredit figures in the current regime; someone trying to make a point on human rights or someone trying to stop a slide back into some of the harsh aspects of the Mao era, which has been heavily promoted as a means of overcoming the increasingly glaring inequalities across the country.

The Chen case has developed into a diplomatic headache for both sides and prompted a lock-down of key internet words, with Beijing’s supercomputers seeking out references like ‘blind man’ and Flight 898, the United Airlines flight that he might take to New York should he take up the offer of legal studies at New York University. The authorities have made sure that there is as little as possible information available to the domestic audience.

The first reference to the escape came in an article on the website of Global Times, in English, focusing on the potential negative consequences for the US providing a haven for Chen: ‘If petitioners’ requests are not met by domestic authorities and turn to the US Embassy, this is not only embarrassing to China but also puts the US in an awkward position.

‘The US Embassy would have no interest in turning itself into a petition office receiving Chinese complaints. It is easier just preaching universal values to the Chinese public, and occasionally helping a few exemplary cases that best illustrate US intentions. It is never willing to involve itself in too many detailed disputes in Chinese society.’

The message was clear: the Americans can get on with the serious diplomacy of one of the most important relationships in the world or it can turn itself into some kind of international citizens’ advice bureau taking up the complaints of every Chen, Choo and Liu.

No-one was more aware of that than the Americans themselves, with the prospect of Chen ruining a key meeting between the two sides involving Secretary of State Hilary Clinton, especially as he then demanded that he accompany her home on her plane. Most likely with a bit of American arm-twisting, Chen then announced that he would take the option of a kind of internal exile. For a while it seemed that would calm the situation and allow both sides a face-saving route out of what was an increasingly embarrassing confrontation. But the medieval brutality of the Chinese mistreating Chen’s family re-awakened the notion of his taking the option of studying in the US.

With the story off the front pages and no longer on the television news, Chen was allowed to apply for a passport and make ready for a move to New York City. He has since taken up a place at NYU law school.

As the Americans would say, it’s a win-win situation: the Obama administration has not been forced to back down in the face of Chinese intransigence; China’s face has been saved because there was no public humiliation of the authorities through Chen’s boarding Mrs Clinton’s plane and Beijing well knows that the nascent lawyer’s propaganda value will decline to zero once he has been in the US for a few months. But they will know that the next Chen will have to be treated a bit more circumspectly.

And that is the value of the media and an even quarter-free press: the word gets out; the globe is now a media village; nothing stays secret for long in the face of newly-empowered citizen-journalists with their (ironically Chinese-made) mobile phones.

Article Source: articles base

Leave a Reply