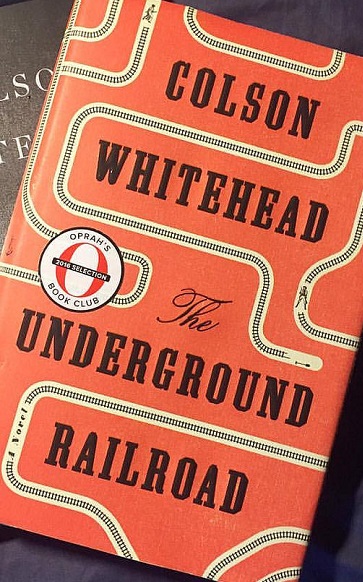

If anyone is looking for a good, thought-provoking summer read, The Underground Railroad, by Colson Whitehead, is one I would certainly recommend. The novel is a fictional slave narrative account of a teenage orphan, Cora, who escapes her hellish life at a Georgian cotton plantation in a desperate attempt to procure freedom in the north. Her journey northward is starkingly different from what one would expect; it deviates from traditional historical fiction works, as the Underground Railroad on which she travels is literally as it sounds: it is a network of train tracks, locomotives, and subterranean stations.

Readers follow Cora as she stops in different states throughout her journey, which on first glance, appear to be havens, but in reality, mask treacherous plots designed for black inhabitants, namely practices of covert medical experimentation and sterilization. Cora becomes increasingly disillusioned as her hopes for freedom become challenged by the shackles that bind, which are more firmly entrenched than they outwardly appear.

The novel was selected for the Oprah Winfrey Book Club in 2016, was the winner of the 2016 National Book Award for Fiction and the 2017 Carnegie Medal of Excellence, and, recently in April, won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. Given its critical acclaim, it is little surprise that this novel won. Interestingly, however, I discovered an article by Jay Nordlinger, written last year but re-published the day after the 2017 Pulitzer Prize announcement, under a new title, A Problematic Prizewinner of a Novel, which criticized controversial aspects of the novel, specifically, Whitehead’s moral and historical judgments. Given the re-emergence of the article, it appears the author’s sentiments have not changed.

Nordlinger, criticizes the didactic character of the novel, chastising that “teaching in a novel should be accidental, not bluntly striven for.” To him, the novel was pedantic, as it appeared to “spell out” events for the reader. He seems to believe that Americans are not so ignorant of their history. He goes on to further criticize, this time the treatment of Ethel, who secretly houses Cora when she reaches North Carolina. Ethel is mocked for her girlhood desire to serve as a missionary in Africa, which may be a tolerable criticism; but, when Whitehead continues to mock her as she is being lynched by a white mob, Nordlinger sees this as crossing the line into hurtful and hateful.

Nordlinger’s caustic review aside, most reviews laud Whitehead: Reviewers regard the novel as a timely work that projects black voices onto a genre, that up until recent years, was the preserve of white, male writers. Whitehead, as well as other black Pulitzer Prize recipients, remind us that black storytellers are creating provocative and insightful works on racism and deserve to be read.

The other winning works, by black writers, all focus on racism—“Sweat” a play by Lynn Nottage explores the devastating cycle of violence, prejudice, poverty and drugs; Olio a poetry book by Tyehimba Jess, writes the Pulitzer Prize committee, “challenges contemporary notions of race and identity”; and reviews in The New Yorker, by theater critic Hilton Als, according to the committee, scrutinize “the shifting landscape of gender, sexuality and race.”

The choice of these winners reflects the committee’s recognition that these voices that must be heard—because despite the change in public attitudes toward racial inequality so far, we have not realized the promises of the post-racial society.

Leave a Reply