Effective altruism means giving logically through high-impact solutions to maximize utility. Given the connection between our mission to advance smarter voting methods and the resulting policy that shapes our world, we maintain that The Center for Election Science (CES) falls squarely within the scope of effective altruism.

What’s effective altruism? Much of effective altruism looks at helping those in developing countries. The idea here is that a dollar goes a longer way in these countries and that the overall translation of initial dollar to end result is efficient. For example, one of the charities supported by The Life You Can Save indicates a $50 donation can restore someone’s sight. That’s pretty amazing. Other listed charities offer cost-effective solutions to deworm children and fight malaria.

Peter Singer, an Australian philosopher, is one of the minds behind the effective altruism movement. In his books The Most Good You Can Do and The Life You Can Save, he spent most of his time highlighting this idea of direct impact in developing countries. But he also made an exception and addressed the importance of charities that have a more complicated route to their end impact, such as fighting global warming.

Global warming is a more complex cause. As humans, we’re not nearly as wired to prioritize global warming as we are the benefits of helping a blind person to see again or deworming a child so that they can get back in the classroom. Any impact on reducing CO2 or increasing CO2 absorption is delayed. Further, while we’re experiencing the early effects of global warming, the real disasters are yet to come. Still, the potential benefits of mitigating global warming are huge. That is, we get a livable Earth to exist on for generations to come for the most intelligent sentient beings in the universe that we know of—us!

Global warming is a more complex cause. As humans, we’re not nearly as wired to prioritize global warming as we are the benefits of helping a blind person to see again or deworming a child so that they can get back in the classroom. Any impact on reducing CO2 or increasing CO2 absorption is delayed. Further, while we’re experiencing the early effects of global warming, the real disasters are yet to come. Still, the potential benefits of mitigating global warming are huge. That is, we get a livable Earth to exist on for generations to come for the most intelligent sentient beings in the universe that we know of—us!

CES advances a similar kind of complex cause with (warning: big claim ahead) an arguably even greater impact than mitigating global warming.

Our mission is to empower the public through advancing smarter electoral systems, with particular focus on the voting method. A voting method refers to what you put on your ballot (ex// choosing one, choosing unlimited, ranking, scoring) and what’s done with that information to get a result (ex// adding tallies, simulating pairwise comparisons, simulating sequential runoffs).

On its surface, that doesn’t sound terribly exciting. Like global warming, when you unpack it, there’s a lot of complex science and math. Similarly, when you look at the potential impact, we see a dire situation and extreme need.

So why should you care about an organization that places so much importance on the voting method?

Focusing on voting methods means providing meaningful participation in democracy. That meaningful participation translates to representative government and better decision making in every area of public policy—all at once. This strikes at the root of social issues in a way that few other philanthropies can.

The voting method ultimately determines who decides to run, what ideas get heard, and who writes and carries out policy. You can look at our article on Bloomberg’s decision not to run for a full analysis on how the voting method relates to these points. A change in voting method promises to completely change political discourse and resulting policy.

Whatever you do, don’t let that word “policy” slip by too quietly. Policy is what determines the quality of the schools and hospitals that you and your children go to, whether the air you breathe is clean, and whether we keep our planet’s CO2 levels under control. Policy is what determines whether we spend more money on bombs or building and repairing our transit system. Policy determines your rights and individual freedoms as a person.

Simply, policy determines what you and your family see when you walk out your door.

Clearly, voting methods are important because they give us the power to affect policy. And policy includes even leviathan-sized causes like global warming. But is there an opportunity gap for voting methods that needs filled?

Yes, and that gap is startlingly large.

A Princeton study looked at the predictive value of the average voter’s stance on policy (that important p-word again) and the policy that gets enacted. The average voter’s predictive value? Zero. The study showed that the current way we vote is an ineffective tool for policy change. Add to that a government whose approval rating sinks into single digits. Now you start seeing more than red flags. These are outright critical system failures.

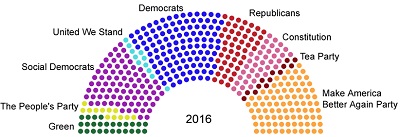

What’s the voting method that causes this failure? It’s plurality voting complemented with a nearly universal winner-take-all system that extends from the local to federal level. What’s this terrible plurality voting, you ask? Plurality voting is the vote-for-one, most-votes-wins voting method that’s ubiquitous with voting itself. It’s ubiquitous even within the public consciousness. For example, if you were to ask a random person what voting was, they’d likely just describe plurality voting to you. Voting methods are not something society normally thinks about.

But we think about voting methods—a lot.

Here’s how bad other experts think plurality voting is. The London School of Economics and Political Science has an organization, Voting Powers and Procedures, that looks at voting methods. At a 2011 conference, to try to get an idea of how academics felt about different methods, they decided to vote on the best single-winner voting method. The method that came in last with zero support was plurality voting. The method with the most support was approval voting. (Side note: CES is the leading advocate for approval voting within single-winner government elections.)

We’ve established that voting methods have the opportunity for enormous impact given their connection to policy. And we know there’s room for growth given that we use the worst voting method.

But why are we the right organization to change this?

We take a science-oriented approach that’s grounded in real-world logistics. That’s largely why we talk about approval voting so much for executive elections. Not only does analysis reveal approval voting as a superior voting method, but it also has features that make it easy to implement.

We may recommend another method in a different context, such as with an experienced electorate, a sophisticated private organization, or a small group. And we have offered other solutions, such as a queuing algorithm complemented with score voting for our work with The Webby Awards. We also look at an array of options for multi-winner elections, particularly proportional voting methods.

Despite our small size, the talent behind our advisory board, board of

directors, and staff has translated to us being sought-after experts. We’re sought out by state and local governments, private institutions, political parties, and other advocacy organizations. Plus, we’re recognized as experts by media like Popular Mechanics and MSNBC.

We’re excited to have accomplished what we have. Recently, we celebrated the completion of a nationally representative presidential poll that compares alternative voting methods. We’re now collaborating with highly experienced researchers at the Paris School of Economics. We’ll ultimately be seeking peer-reviewed publication, which reiterates our data-driven model.

While we’re excited by our accomplishments, our capacity is limited by funding. From a large donor’s perspective, this is good because it sidesteps any risk of diminishing marginal benefit and creates an open opportunity. To get where we are now even, it took many early supporters who gave generously within their means. Organizations focusing on our scale normally have multi-million-dollar annual budgets. Many organizations start with either a wealthy founder or have early funding through other means such as a large foundation or philanthropist.

While we’re excited by our accomplishments, our capacity is limited by funding. From a large donor’s perspective, this is good because it sidesteps any risk of diminishing marginal benefit and creates an open opportunity. To get where we are now even, it took many early supporters who gave generously within their means. Organizations focusing on our scale normally have multi-million-dollar annual budgets. Many organizations start with either a wealthy founder or have early funding through other means such as a large foundation or philanthropist.

Regarding philanthropists, let’s be clear. Philanthropists have absolutely pioneered benefits for humanity, benefits that would not have occurred otherwise. Without philanthropic intervention, some of those benefits would have—at best—been delayed for decades. For example, the reason we have The Pill is because of philanthropist Katharine McCormick. Having just a few or sometimes even one philanthropic leader makes all the difference.

We don’t have that advantage of large philanthropic intervention for smarter voting methods. Not yet.

With a large-scale budget, our organization could step on the gas when it comes to advancing smarter voting methods. Consider some of the following projects we’d love to take on with greater capacity:

Direct Impact

- Educational campaigns alongside voting method ballot measures

- A sister 501(c)4 organization for strategic ballot initiatives (historically the way forward for voting method reform)

- Consulting for large organizations and governments to use smarter voting methods

- Wizard/ballot generation/ calculation software for groups to run smarter elections

Supporting Work

- Advanced research in targeted localities comparing different voting methods

- Research analyzing whether switching voting methods affects the agreement between government policy and electorate opinion

- Reports and white papers on electoral systems

- School materials & lesson plans on voting methods

Existing focus on voting methods is on needlessly complex methods that—while an improvement—still distort the support of candidates trying to break through. In many cases, that complexity has unfortunately caused the reform method to be repealed despite it being technically better than the status-quo.

Other efforts focus around issues that—while important—don’t offer the same opportunity for impact as going after the voting method. Often times, reform solutions miss the connection on how voting methods help them achieve the outcomes they want.

A good example of this is overlooking proportional voting methods and instead focusing on independent commissions as a way to address gerrymandering. Very well-meaning organizations consistently misread this problem with a solution that has shown not to work when used in good faith in other countries. We addressed this in our article looking at the concept of majority in voting.

We can do better. CES has clear solutions. We target the voting method, and we do so intelligently.

Of course, not everyone has the capacity to support an organization at a hundred thousand or million-dollar level. But for those who do have that capacity, I’ll tell you this. You can change the world in a very real and meaningful way. You won’t be alone either. You’ll have the encouragement of all our supporters who have already donated their time and money. Additionally, you shouldn’t be surprised when you hear how you inspire others.

Pushing smarter voting methods has the potential to change lives in the world at a fundamental level. There are few opportunities for this level of impact.

The question now is: What are you willing to do to create the kind of world you want to live in?

Also see our entire section called Voting Methods Central.

Leave a Reply