The alarm has been sounded that we are witnessing the return of fascism. Experts point to a noted rise in extreme right politics in elections and in visible armed groups, as well as in the police and military. Understanding what fascism is and how it manifests is important to determine if these concerns are justified.

It turns out that the meaning of fascism is hotly debated. It has been linked with populism, nationalism, and narratives of renewal/rebirth after a perceived crisis or decline, but research shows these links are at best inconclusive.

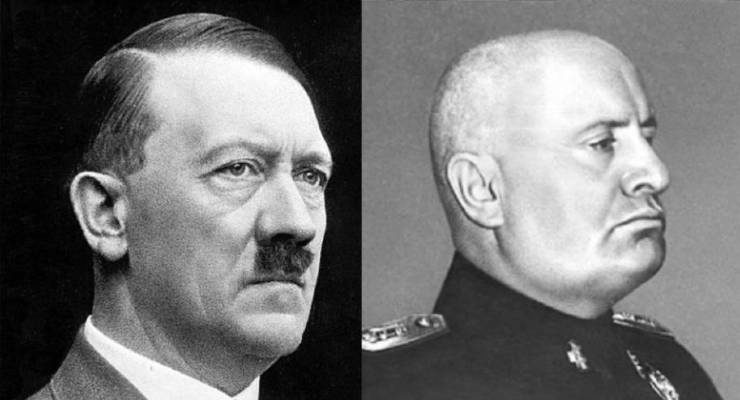

Some studies use the term ‘neo-fascism’ to suggest there is one consistent ideology with different manifestations that change with time. Others argue fascism only really describes a political movement in early twentieth-century Europe. It has even been claimed the term only properly applies to Benito Mussolini’s regime in 1930s Italy.

There is also debate over fascism’s relationship to capitalism. Marxists highlight how fascism maintains the capitalist status quo. While democratic analysts point out how fascism acts to radically change political and legal institutions. This mix of revolutionary and reactionary qualities has led to a divide between the liberal and Marxist explanations of fascism. Academic studies tend to focus either on fascism’s socially transformative drive or its economically conservative aspects.

An alternative perspective was offered by Karl Polanyi, who argued fascism is a ‘solution’ to the weaknesses of a society based on self-regulating markets and their institutional supports (e.g. Gold Standard monetary system, liberal state). Polanyi was writing in the 1930s and noted how the market system had become unstable in the Great Depression and social collapse loomed large. In response, capitalist and ruling elites in Europe and elsewhere turned to fascism to save the collapsing system, achieving success in Italy and Germany, as well as other countries. Their success is tied to the instability of the market economy. Fascist regimes emerge only when elites feel they are faced with no alternative to protect the status quo.

However, Polanyi wrote the real ‘trick’ needed for fascism to work is taking popular resentment caused by liberal capitalism and redirecting it against democracy. By using democracy as a scapegoat, capitalism can co-exist with authoritarian politics. Industrial production and private ownership can be protected while individual rights and institutions of popular representation were abolished.

Fascist ideology is rooted in anti-individualism, which denies both the value of the individual and its equality. Polanyi suggested there are two forms anti-individualism can take in fascist ideology. One is associated with a philosophical tradition known as ‘vitalism’, which privileges non-conscious aspects of human life supposedly located in the body and expressed through natural forces. Vitalist fascism negates any sense of ethics, ego, or rationality in favour of striving for an organic state of social cohesion “untroubled by moral conscience” (1935: 385). The other way fascism’s anti-individualist ideology is expressed is in totalitarianism, where individuality is subsumed entirely within larger social entities such as a state or a religion. These entities are seen as the basic units of society; individual social relations are defined only through them.

Polanyi saw fascist regimes exhibiting these ideas in different quantities. He observed the Nazis adopted a vitalist understanding of social order as “perfect harmony” where “every animal is certain to end in the belly of another animal” (Polanyi 1935: 379-80). However, the Nazis used this racism to achieve totalitarian ends, where subjects relate to each other through representations of ‘blood’ and “race.”

Both vitalist and totalitarian forms of fascism de-centre the individual. In vitalist fascism, “the person is not yet been born into society;” whereas in totalitarianism the individual “has been absorbed” into society. Both iterations are thought of as an extreme response to the problem of the individual in modernity, related to the need for moral autonomy and social belonging, by abolishing the concept of the individual entirely.

Polanyi leaves us with three important points for understanding fascism

- Fascism comes in many forms but all are linked by their shared anti-individualism. Fascist politics uses nationalism and racism to gain power and implement anti-individualist ideology. In this sense, fascism is not only an extreme form of racism or nationalism. It is fundamentally about eliminating the individual as a political agent.

- Fascism’s anti–individualism is both economically reactionary and socially radical. In Europe, fascism protected capitalism, but at the same time, it attempted to radically transform society by abolishing its democratic institutions and the very basis of human consciousness.

- Circumstances make fascism grow. Polanyi saw it as a symptom of the instability of market-based systems, and more broadly, the incompatibility between democracy and capitalism. Fascism is always a political possibility when markets are put above the well-being of individuals.

Contemporary authors use Polanyi’s work to look at how market-driven social problems under neoliberalism have laid the groundwork for fascism’s “second time around.” The socially radical dimension of fascism uses notions of race and nation to turn dissatisfaction with capitalism into anti-democractic politics. As we emerge from a pandemic that has heightened social isolation and constrained individual agency, Polanyi’s analysis reminds us that solutions to rebuilding societies, as well as to tackling existential threats such as climate change, must find ways to facilitate the conscious participation of individuals. It is at this level that the struggle against fascism ought to be waged.

This article is based on research by Kris Millett.

References

Polanyi, K. (1935). The Essence of Fascism. In J. Lewis, K. Polanyi, D. Kitchin (Eds.), Christianity and the Social Revolution (pp. 359-390). New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Polanyi, K. (2001). The Great Transformation. 2nd ed. Boston: Beacon Press.

Jack Jones says

Blown away , great article !