Runoffs get touted as a solution for vote splitting between similar candidates and overall better elections. Certainly, just about anything is better than the choose-one plurality voting that the US uses so extensively. But are runoffs really the great solution we make them out to be? (We already know that—like any voting method—runoffs can’t guarantee an absolute majority.)

The French use runoffs for their presidential elections, so let’s look at them. And while we’re at it, let’s look at their whole presidential election process, which they do every five years—and is happening right now.

France starts with primaries, though not necessarily the kind Americans are familiar with. In France, parties themselves can choose to internally pick their nominees, whereas US primaries generally have more public involvement. Further, French parties themselves decide which candidates are even eligible. Parties do this by requiring that candidates have a minimum amount of party member support.

Interestingly, parties can enter into alliances where one party decides not to run a candidate. Two parties took this approach this time. Candidate Bayrou from the Democratic Movement Party made an alliance with the similarly centrist En Marche! Party founder, Emmanuel Macron. The French equivalent of the Green Party made their alliance with Socialist Party candidate Benoît Hamon.

Interestingly, parties can enter into alliances where one party decides not to run a candidate. Two parties took this approach this time. Candidate Bayrou from the Democratic Movement Party made an alliance with the similarly centrist En Marche! Party founder, Emmanuel Macron. The French equivalent of the Green Party made their alliance with Socialist Party candidate Benoît Hamon.

Right away, that parties are entering into coalitions at all is telling. Why? They’re doing this because they know there will be significant vote splitting between similar candidates. Even a runoff won’t prevent vote splitting.

After parties have their nominees, France’s Constitutional Council determines the official candidate list. Making this list requires sponsorships from people already in office—a clear conflict of interest. For example, this hurdle meant that a large-scale, citizen-driven initiative called LaPrimaire.org wasn’t able to get its candidate on the ballot.

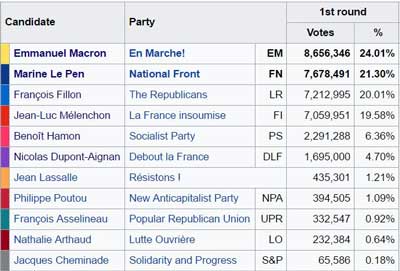

The Council identified 11 qualified candidates on its official list this year. All of France saw these same 11 candidates. Compare that to the US, where voters see drastically different candidates depending on which state they live in due to wild variation between state-by-state ballot access laws.

France normally holds off on debates until the second round, but for the 2017 election year they made an exception. The first-round debate consisted of the top five candidates. This included Socialist Party candidate Benoît Hamon who was polling between 10 and 15%. This is another departure from the US where a private organization controlled by former party leaders restricts participation to major-party candidates by requiring polling at 15% before entry. Yet another departure includes the debate rules themselves. The French debates allow candidates to direct questions to each other whereas the Commission On Presidential Debates in the US forbids this.

And just to really depart from the US’s exclusionary approach, France’s second presidential debate invited all 11 candidates. The US may have something to learn from this free market approach.

Following the debates, the first-round elections were held on Sunday, April 23. Yet another difference here. France’s election is not held in the middle of a work week like it is in the US. This access to the polls, broad candidate coverage, and choice diversity may help to explain France’s voter turnout. Among eligible registered voters, France experienced an 80% voter turnout. Compare that to the fewer than 60% of US eligible registered voters who turned out in 2016.

The results of the first round? The top four candidates were all within five percentage points of another. But with plurality voting, it’s hard to know the real candidate support due to the open invitation to vote splitting.

Interestingly, among the two candidates barely making it to the next round was the 39-year-old centrist Emmanuel Macron. Those familiar with the center-squeeze effect may find this surprising. Typically, centrists fare poorly with multiple candidates under plurality voting (even with a runoff). The reason for centrists’’ typically poor performance is that their vote can split with similar candidates who surround them on multiple sides.

Macron may have had some advantages here, however, that let him get by. For one, he managed to get a fellow centrist, Bayrou, to not run at all. Also, he was able to reach out to leaders across the political spectrum to get a wider base of support. Having the center-right candidate François Fillon marred in controversy from self-dealing for his wife likely helped Macron’s cause as well. The truth is, results from choose-one plurality voting—again, even with a runoff—can be unpredictable, particularly when there are many candidates.

Macron may have had some advantages here, however, that let him get by. For one, he managed to get a fellow centrist, Bayrou, to not run at all. Also, he was able to reach out to leaders across the political spectrum to get a wider base of support. Having the center-right candidate François Fillon marred in controversy from self-dealing for his wife likely helped Macron’s cause as well. The truth is, results from choose-one plurality voting—again, even with a runoff—can be unpredictable, particularly when there are many candidates.

Macron’s moderate ideology is reflected in his policies. His tax policies provide more favor for corporations—not surprising given his profession as an investment banker. He’s also promised to focus funds into renewable energy. Plus he favors tightening France’s relationship with the European Union.

The other candidate who advanced, Le Pen, appears more typical of this voting method’s behavior. She falls on the extreme end of the political spectrum, so she potentially had fewer issues with vote splitting than Macron had to deal with. Le Pen likely also benefited from the center-right candidate François Fillon’s controversy with his wife.

Le Pen’s policies resemble that of US president Trump in a number of ways. She wants to ban head scarves, shut down “extremist” mosques, deport all immigrants present illegally, and limit new immigrants.

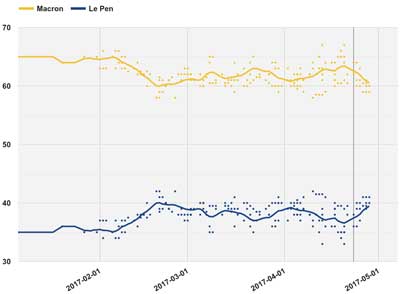

Unlike Trump, however, Le Pen is unlikely to do as well for several reasons. For one, Le Pen has just two weeks between rounds to catch up from a 20-point polling deficit. Macron doesn’t have the within-party division that Clinton experienced after turning off Sanders supporters, so there’s less risk of him losing those voters in the second round. And with just two candidates, there’s no one else to lose votes to. Finally, Macron doesn’t have to deal with any French equivalent of the Electoral College wild card. Therefore, it seems that—minus some large revelation—Macron should beat Le Pen in the runoff quite easily.

This large 20-point polling discrepancy between Macron and Le Pen highlights how random the first-round election really is. This makes a strong case that significant vote splitting occurred. It’s difficult to say who the top two candidates would have been using a voting method that more accurately reflects candidate support. Perhaps a more sensible voting method would have advanced the populist-oriented candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon. Maybe even the marred François Fillon could have pushed forward to the second round instead of Le Pen. Surely, many of those with little support would have fared better under a system where a wasted vote is less of an issue.

Now that we have a picture of the French system as it is, the next step would be to see it as it could be. We’ve seen a strikingly different picture of French elections under different voting methods before. Fortunately, we’ll all get another look as an alternative voting method analysis is again underway for this election. We look forward to that analysis by researchers including Jean-Francois François Laslier, who is on the advisory board of the Center for Election Science. We’ll be waiting in anticipation.

Leave a Reply