Ruth Carter-Lynch wants to be the next Supervisor of Elections in Broward County, Florida. The Democrat, a long-time local businesswoman and Democratic activist, is running in the August primary against several contenders. She is stressing the importance of registering citizens and making it easy and convenient for people to vote.

The Democrat who wins the primary will most likely be the next election chief; Broward County is a Democratic bastion in South Florida — Republicans have only served in the office in recent history when a GOP governor removed a Democratic Supervisor of Elections for poor performance.

The foundation for Carter-Lynch’s beliefs, in part, were formed during her childhood, when she lived in segregation in the Mississippi Delta region in Greenwood, MS., the “Cotton Capital of the World,” she writes in a draft of a book she has not yet completed. She has given Democracy Chronicles a look at her memoir, which will be excerpted below without editorial intrusion by me.

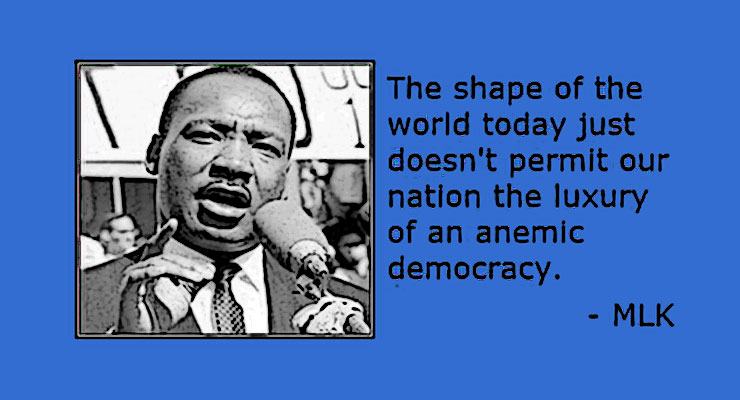

Carter-Lynch took time out from campaigning online during the Coronavirus pandemic to recall the time Civil Rights leaders such as Martin Luther King, Jr, and John Lewis, now a Congressman from Georgia, came to her community. The Rev. Jesse Jackson, who years later sought the Democratic nomination for president twice, was part of the civil rights organizers who visited Greenwood.

Jackson, known for his powerful oratory and trailblazing political organizing, enthralled the 1988 Democratic National Convention when he encouraged people to “Keep hope alive.”

African-American residents of Greenwood had to house and feed Jackson and other Civil Rights leaders, according to Carter-Lynch. This happened because laws and customs at the time did not allow some Americans to stay at “white only” motels and eat at restaurants that were only open for the dominant white race.

What follows is writing that she has shared with Democracy Chronicles.

–DRAFT–

MY LIFE IN GREENWOOD, MISSISSIPPI

“The Cotton Capital of the World”

June 19, 1992

I was born in the great city of Greenwood, Mississippi, on February 13, 1953. I will never forget sitting in my 10th-grade class; Mrs. Hammond was the English teacher at Threadgill High School, our Black High School, when all the juniors and seniors started running down the hallways, saying, “Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. is on the playground speaking and will be marching after the speech.” The Black playground was down the street from our high school, less than two blocks away; we all were excited, exhilarated and scared, all at the same time. Mrs. Hammond suggested we all go home to our parents until things settled down.

In any event, I went home, and my grandmother asked me, “Why aren’t you out there marching with Dr. King?” She added that Dr. King needed the numbers and she felt I might learn something. In those days, you did not talk back to your parents, you just did as you were told; another story I will eventually tell. So, off I went.

Most of the people on the playground were high school students and a few community activists. Just Dr. King’s presence was enough to make you feel special. At that time, I wondered, why would a man of Dr. King’s stature care about what happened in Greenwood, Mississippi, to Colored People.

That questioned was answered as I grew older and realized that what was happening in Greenwood, Mississippi was happening to Black people all over the United States and the World. Little did I realize that that one day in Greenwood, Mississippi would change the total trajectory of my entire life.

At the meeting, he talked about how important it was for us to make sure we register to vote and that we had to assist each other with the process. Plus, as young people, we didn’t have the same heightened sense of fear as the older adults in the town, which is also true today.

After the meeting and march through the impoverished parts of the city, the local activists made sure Dr. King and his colleagues had a safe place to stay and food to eat. I can remember John Lewis, now a Congressman, staying across the street at my cousin’s family home, because my cousin’s mother and father were staunch advocates for voting rights, as was my grandmother.

But she was more subdued with activism, plus she worked for some very prominent lawyers and doctors in our town as a domesticate. Still, my grandmother made sure that my brother, Henry and I participated.

I remember Dr. King saying that we can’t let this be a one-time thing, that we had to continue the non-violent fight for our voting rights and justice for our people.

Soon after that experience, Dr. King went to Memphis, TN. to assist the union workers there and was assassinated at the famous Lorraine Hotel. As soon as we heard the news, all hell broke loose — everyone ran out of their homes and the younger generation began to tear the city apart; setting fire to White businesses, and any business in our neighborhood that were not Black-owned.

I have to say that was one of the most fearful times of my life. My grandmother made sure that my brother and I were not part of the turmoil. She said, “White folks are going to regret killing King.” She felt he was the only person keeping the lid on a racial war.

White folks have had their feet on the necks of Black folks far too long. Well, my grandmother said, maybe it will finally come to an end. I can still remember the water hoses and dogs being turned loose on protestors. We lived on the corner of Pelican and Young street, where people would meet to begin protesting at all the White stores in our neighborhood. Of course, the proprietors would call the cops and they would descend on the protestors with a vengeance.

After all the violence and destruction, members of the White Chamber of Commerce decided it was time to sit down with the community leaders, pastors and anyone who they felt had a say in how to fix the situation. Their ultimate remedy was to slowly allow the Black Community to shop in the entire downtown area along with the White Community.

However, it would take a little bit longer to get the White restaurant owners to agree to allow Black people to dine with their White customers and to integrate the schools, which meant busing all the Black children to the White schools.

This was a unique experience for me — the first few months I was called the “N” word so much it felt like my middle name. I remember going home in tears and my grandmother wanted to know why I was crying, and I said, they keep calling us “N” word and it hurts. She said, “Is that your name?” and I said no, and she said, “If they don’t call you Ruth or “Gee Gee” (my nickname), they are not talking to you. So, go outside and play and ignore them. I sent you there to get an education, not to become a crybaby.” Therefore, that was the end of that little scenario.

Hence, I am first-generation integration for the Greenwood, Mississippi public schools, which is another experience that warrants its own commentary. That experience further solidified how important it was to continue to fight for voting rights and equality.

I will never forget my grandmother saying, “Now that you have graduated, it is your job to fight for the rights of others. A lot of people bled and died for you to have this opportunity. You are one of the lucky ones, everybody cannot afford to get an education. Why do you think I made sure you went to Catholic school?”

My grandmother continued, “Catholic school provided the best education money could buy and you got to go for free. That’s why you were prepared to compete with the White children once you went to Greenwood High,” the White high school in my hometown.

Out of 227 Black students that went to Greenwood High, the second year, class of 1970-1971, only 27 graduated, and I was one of the 27. This was one of the proudest moments of my life because I was the first person in my family and immediate neighborhood to go to college, Mississippi Valley State University on scholarship. Therefore, as you can see, I was born into activism and the fight; and it never stops.

For more see Ruth Carter-Lynch’s campaign website or Facebook page.

Ruth Carter-Lynch says

Thank you, Steve and Democracy Chronicles, for allowing me to share a little bit of my history and that of the segregated south. I feel it a privilege and honor to be a servant leader in our communities throughout Broward County. I will always have a deep sensitivity surrounding voting rights. I can remember my grandmother and a number of her friends going to the courthouse at least 15 times or more before they were granted the right to vote. Those were trying times and I am obligated to continue to fight for voting rights. I witnessed those who put themselves on the line and died so that I could have the many opportunities I enjoy today. I will be forever honor and be grateful to them all. Thanks again.

David Anderson says

The massive disenfranchisement efforts of the Republican party (ADMITTED, actually ADMITTED) mainly but not exclusively in the South beggars belief.

Living where I do (Manhattan, NYC) real live Republicans are about as rare as pandas – we don’t see them in the wild so I never get a chance to nail them down on that particular policy of theirs. When I do catch one in my net I usually ask him (invariably the male of the species) about their feelings about religion/church and state vs our founding fathers’ original wishes) or their crappy foreign policy ideas.

They struggle and get loose (I kid you not, I’ve had them “run out” of an awards dinner, two dinner parties and a street meeting) when I ask them these kinds of questions)- so I never get to ask them about their biggest outrage – the purposeful disenfranchisement of minorities in particular. I need a bigger net. :-)

Great article – thank you!

D.A., NYC