Voters aren’t always honest. But what would it look like if they were? We found out.

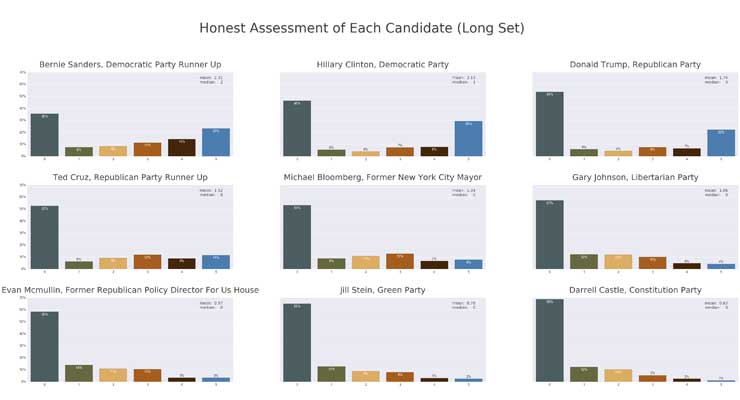

Here’s how we got respondents to be honest. We asked them to indicate on a 0-5 scale how much they would like each candidate to be elected president—regardless of the candidate’s actual likelihood of being elected. (We’ll talk about actual score voting in a later release.)

On top of that, we thought we’d add some extra candidates, since the voting method can actually change who decides to run. In addition to the two major-parties, the Green Party, and Libertarian candidate, we’ve also included five more. These include other third-party and independent candidates; candidates from the major-party primaries; and Bloomberg, who decided not to run because he feared splitting the vote with Clinton.

We could have just shown you the averages, but the distributions within each candidate were interesting enough that we decided to include them as well. Some candidates were really polarizing, as you can see.

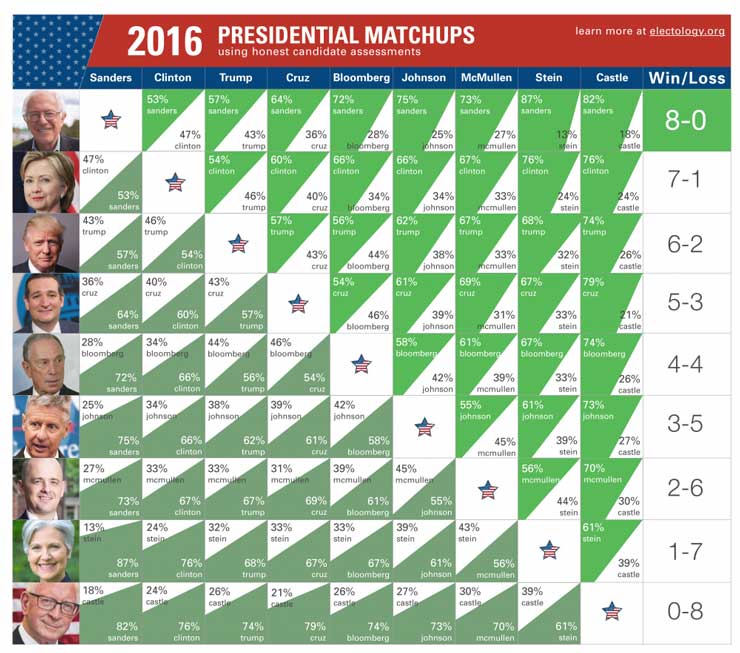

Sanders turned out to be the most honestly preferred candidate. For one, he’s scored at a zero much less often than the other candidates. But how would Sanders have done if he went up against each candidate one-on-one? It turns out, he’d do very well.

We might look at Sanders’ win here as being a “true” Condorcet winner. A traditional Condorcet winner is someone who wins against everyone one-on-one, simulated through ranked (1st, 2nd, 3rd-style) ballot data. But that data isn’t necessarily honest. There’s a theorem which proves that no voting method in an election with more than two candidates is immune from all tactical voting. This theorem is called the Gibbard-Satterhwaite Theorem (this linked explanation is from our vice-chair, PhD candidate Jameson Quinn).

That’s why this pairwise comparison from our scale is a little different. This wasn’t a voting method in the sense that you can’t trust people to remove strategy when trying to get someone elected. This was an honest assessment.

The rare case where we can expect voters to be honest is an election with exactly two candidates. This is why we can use this honest assessment data to simulate head-to-head matchups.

The way we did this was that we looked at how each respondent scored each candidate. When a respondent scored one candidate higher than another, that counted as a vote towards that favored candidate in a head-to-head election. We repeated this with every respondent and every combination of candidates to get the table you see above.

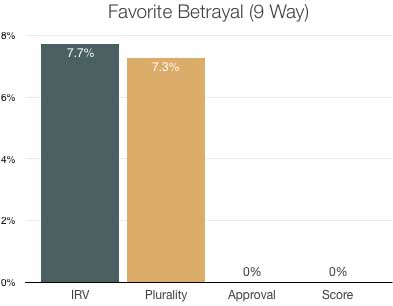

You can see from our last article that there were indeed instances of dishonesty/tactical voting in the voting methods we used. As an example, we looked explicitly at when respondents did not put the maximum support for their honest favorite candidate.

We saw the most cases of voters betraying their honest favorite with instant runoff voting/ ranked-choice voting. This was surprising to us. We expected voters using instant runoff voting to not always choose their honest favorite, because this can indeed hurt them. But we expected this behavior to be more prevalent with regular choose-one plurality voting. This means that some voters were illogical, possibly because instant runoff voting tends to be more complicated.

We saw the most cases of voters betraying their honest favorite with instant runoff voting/ ranked-choice voting. This was surprising to us. We expected voters using instant runoff voting to not always choose their honest favorite, because this can indeed hurt them. But we expected this behavior to be more prevalent with regular choose-one plurality voting. This means that some voters were illogical, possibly because instant runoff voting tends to be more complicated.

Respondents could have just been confused by how to best strategize compared to regular plurality voting. Predictably, the number of voters going against their favorite under plurality voting was higher with this 9-candidate scenario versus when they only had four candidates, as we analyzed in the last article. There are simply more scenarios and opportunities to be tactical with more candidates.

Looking at approval voting and score voting, we saw zero instances of voters going against their honest favorites. Approval voting has voters choose one or more candidates (most votes wins). Score voting has voters score each candidate on a scale (highest score wins). Logically, voters should always support their honest favorite with these methods, as this approach is always in the voter’s interests. And that’s exactly what we see here, which is reassuring to see in practice.

We can’t expect voters to be honest. It’s proven that there’s always some incentive to be tactical when a voting method is used with more than two candidates. But what we can do is see how certain voting methods encourage voters to be honest in certain ways. Like when they’re demonstrating their favorite.

We hope you enjoyed seeing what happens when voters indicate what they really thought—particularly when given a larger range of choices.

–

Special thanks to our analysis team Jameson Quinn, Graham Anderson, and Neal McBurnett.

Leave a Reply