by John Amaruso

The American Constitution is the guiding document for our government and our people. It’s the first of its kind to have warranted support from the citizens it would ultimately govern over when it was introduced over 200 years ago. It went through months of intense deliberations, being altered and modified multiple times by some of the brightest and most gifted minds of that era. Leaders like George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, Benjamin Franklin, and James Madison who all came from different backgrounds, different experiences and different viewpoints, were able to come together to form a document which would ultimately become the highest law in the land. All this in a country which overtime would see dramatic changes in its political, social and economic make up. The Constitution’s flexibility and ability for open interpretation allowed for a consensus on the matter of a federal government.

It was Benjamin Franklin when signing the Constitution who aptly put it:

“I confess that there are several parts of this constitution which I do not at present approve, but I am not sure I shall never approve them: For having lived long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged by better information, or fuller consideration, to change opinions even on important subjects, which I once thought right, but found to be otherwise.”

Benjamin Franklin’s prospect for changes in opinion and thought on the Constitution provide a window into the intent of the Framers to make the Constitution a living document. Despite this, changes to make the 237 year old document more suitable for today’s world are wrought with political consequences and considerable opposition.

According to Jill Lepore, columnist for ‘The Critics’: “Originalism is popular. Four in ten Americans favor it.” Political leaders like Sarah Palin have helped lead the movement against altering the Constitution in any form. Glenn Beck, a former TV host and now popular radio broadcaster has helped organize Tea Party rallys to ‘Take America Back’ as the popular Tea Party slogan would have it. It’s movements like these that bring attention to the issue of our Constitution.

Is it something that should be left as is in order to secure the maximum amount of liberty possible? Is reforming the Constitution the channel of change we need to bring about a more democratic society? Is the Constitution amenable to the sort of ideas that are necessary to pursue political equality for all?

Political equality which stems from the idea of intrinsic equality states that all citizens are to be considered equal in all matters politically, normally simplified to ‘one person one vote’. This principle is fundamental to a democratic society because it is the only principle that is compatible with democracy’s ideals. The alternative, ‘intrinsic superiority’, would undermine all that democracy has attempted to achieve thus far.

Intrinsic equality safeguards against corruption and abuses of power from the majority against the minority in advocating an equality for all approach. Supporting this principle helps protect your own rights through protecting other’s rights, because if we are to deny the rights of one group, when the tables are turned and you are no longer a part of the protected group, your rights could be violated as well. It is this pursuit of self interest that in turn protects the common interest of all and why it is so important that we as citizens of a democracy value and protect this principle.

Keeping all this in mind, Robert Dahl’s pessimism in “How Democratic is the American Constitution?’ on the changes of implementing the reforms that are necessary to deepen our democracy neglects other avenues of change. Institutions like Unequal Representation in the Senate, First Past the Post system and the Electoral College may all seem like fixed institutions, but with a shift in public opinion and the mobilization of the citizens at large, a change that could extend liberty for all and promote political equality is feasible.

While this may have been the intent of the founding fathers, for democracy in the 21st century, this simply does not meet the mark of most modern democracies. What may have been originally designed as a Republic has been morphed into a Democracy through ‘democratic revolutions’, and if we want to see an American society that upholds the standards we say are inherent in our way of life, there are widespread reforms that need to be adopted to better reflect that ideal.

Unequal representation in the Senate remains a thorn in the side of the principle of political equality. The Senate which is comprised of 100 Senators with 2 Senators representing each state was put into place by the Framers as a way to ensure the rights of the states were protected and represented in the Congress. The issues becomes, who really should be the ones being represented? The people who reside in those states, or the purely symbolic entity of a ‘state’? As Alexander Hamilton puts it:

“As states are a collection of individual men which ought we to respect most, the rights of the people composing them, or the artificial beings resulting from the composition. Nothing could be more preposterous or absurd than to sacrifice the former for the latter. It has been said that if the smaller States renounce their equality they renounce at the same time their liberty. The truth is it is a contest for power, not for liberty. Will the men composing the small states be less free than those composing the larger?”

The way the current system works is it allows for the vote of a man in Wyoming to be valued almost 70 times more than that of a man in California. This disparity in population size and representation has allowed for a small minority of the country, about 7.28% to be exact, to be represented by 34 Senators which is just enough to block any constitutional amendment. This leaves roughly 93% of the U.S. population to be represented by the remaining 66 Senators.

Despite the obvious problem which is a lack of political equality among what are otherwise considered equal citizens, the reconstruction of our constitution to meet a more democratic standard is continuously impeded by Senators from the smaller states who want to maintain their grip on power over the legislature. “In one of every 10 especially consequential votes in the Senate over the two decades ending in 2010, as chosen by Congressional Quarterly, the winning side would have lost had voting been allocated by population…”

The likelihood that these 34 Senators who enjoy a comfortable amount of leverage in Congress willingly relinquishing their power for the sake of democracy is slim to none. Despite our best wishes to reform this institution, Dahl says only from a seismic shift in public opinion as well as in the mentality of our political leaders could such a change be brought about. Dahl’s assertion of the consequences of unequal representation in the Senate couldn’t be any closer to the truth. The implications of such a system are far reaching, as the voices of millions of Americans are effectively drowned out by a small proportion of the electorate.

The situation in the Senate also trickles over into the Electoral College, where Electors are decided based on the number of State representatives which are unbalanced to begin with. This stands as one of the biggest impediments to creating a more representative democracy for the simple fact that not every citizen is being represented equally.

Another highly undemocratic aspect is The First Past the Post System which has molded a system that provides incentives for politicians and organizations to reach out only to the bare minimum of voters necessary (51% in most cases), neglecting the other 49% of the population. FPTP’s ‘winner takes all’ system allows any group with a simple majority to take all or a majority of the seats in a given election, thus negating the necessity of reaching out to a broad base of voters. This disproportion of seats gained in the legislature and the amount of votes actually cast for that particular party violates the principle of effective participation.

Meanwhile only a simple majority of the electorate, 52%, support that particular party, while the other 48% are outright losers. This leads to almost half of the voting population becoming disenfranchised citizens who see their vote as pointless if their district decidedly sways in the opposite direction politically.

While FPTP may not be a part of our written constitution, this electoral process stands as a testament to the power of the informal or unwritten parts of our consitutional system. Meanwhile Gerrymandering according to Dahl helps remedy this problem. The redrawing of district lines to fall along party lines is an old practice, dating back to 1811 when the Governor of Massachusetts, Elbridge Gerry, signed a redistricting bill to favor a particular candidate. This led to a situation where entire districts were comprised of voters who lean in one direction politically.

The decisions on how to divide these districts ends up being left to the political parties themselves, bringing about a serious conflict of interest. The partisan battles in Congress over how to district particular regions leads to conflict among political leaders and also leads to what Dahl calls ‘horse trading’ between political parties to create districts that favor their candidates. The most serious of consequences arise when opposing candidates see no incentive to campaign in a district that has already been decided against their party.

The way that Gerrymandering actually works does more harm than good; by stifling political competition, impeding incentives to reform, and embedding political leaders who may be unresponsive to half of the people they are claiming to represent, political equality is in jeapordy. It is this system that literally ‘locks’ in career politicians, creating a danger to opportunity and access to governing which is fundamental to democratic rights. Dahl says that Gerrymandering is an advantage because it limits political competition.

To provide a comparison, in Communist or Autocratic states, the electoral system is either tilted in the ruling party’s favor through rigging and corruption, or is completely designed to allow room for only one party to compete and win. While the means of Gerrymandering may not be Communist or Autocratic, the ends serve the purpose just as well; diminishing the likelihood of another party or candidate to run or hold office. It’s this legalized form of political monopoly that helps career politicians do what they do best; hold office without any incentive to take in alternative ideas or strive for consensus.

It’s this aspect of our electoral system which is extremely troubling, especially if we aim to provide an equal opportunity for all to participate in the political process. The Electoral College is an extension of the unequal representation in the Senate but stands alone as a democratic deficit itself. The Framers when designing the Constitution according to Dahl wanted to ‘Remove the choice of the President from the hands of popular majorities and to place the responsibility in the hands of a select body of wise, outstanding, and virtuous citizens- as they clearly saw themselves.’ To sum this up, they wanted a form of guardianship when electing the President.

There was an attempt to install democratic ideals into the proposal by the Framers. Alexander Hamilton among them had assumed that the people of each State would choose the electors (Dahl). Instead, the constitution assigned that responsibility to the State legislators. Gouverneur Morris was one of the members who disagreed with this arrangement, saying it would lead to factions, and the blurring of the executive and legislative branches. This lack of consensus over how the Electoral College would work left an open void in our election process, ultimately leaving the State legislators to effectively choose who the next President would be.

Meanwhile as stated before, unequal representation in the Senate is reflected in the Electoral College. Since each state is quote ‘entitled to a number of electors equal to the whole of Senators and Representatives’, those states with tiny populations but are ‘entitled’ to two Senators receive a heavier count of their vote in the Electoral College. According to Dahl this inequality is sized up to smaller states having almost two to three times as many electors than if the votes were based on the states population size. This is a situation which is irreconcilable with political equality.

The motive behind lodging all the electoral votes in a single state conveys the intent of political elites; to wield influence and power. The Electoral College has allowed a select few States along with a minority of the population to decide who is the President of all the States. This defect has widespread consequences and Dahl’s outlook on the future of the chance of reform for this institution as bleak. Dahl’s pessimism is palpable when he talks about the inherent defects in the American constitution. He believes unequal representation, FPTP and the Electoral College are highly improbable to be subject to change.

He even goes as far to say they have become embedded deeply enough that they will remain fixed within our constitutional arrangements. It’s this sort of pessimism which leads to the kinds of attitudes that result from these highly undemocratic institutions. This is coming from the author who challenges us to ‘think differently’ about the American constitution. Instead, we should be challenged to think differently about the future and the possible shifts in public opinion which could fundamentally alter the society we live in. Afterall, if you had asked the Framers in 1776 what we should have done about slavery, it would have been an almost laughable rhetorical question. Slavery? What about it? It seems as though Dahl feels the same about the American people and their Constitution.

To put this in perspective, let’s take an example of the kind of ‘seismic shift’ in public opinion Dahl says is necessary for any sort of reform to take place. Within the past few months the Supreme Court has taken up the issue of same-sex marriage, debating over the case of California’s Prop 8 measure which bans same-sex marriage in the state. The issue has been highly contested and the public’s opinion on it has shifted dramatically over the past decade or so. According to a recent poll conducted by the Pew center published in the Kansas City Star, “Just a decade ago, the country stood resolutely, and unambiguously, against same-sex marriage by 58-33 percent, according to the Pew Research Center. Today, Pew says the nation stands for gay marriage by 49-44 percent.” (Kraske 2013).

This type of swing in public opinion in favor of what was only a decade ago a closed debate shows the possibility of rapid change, especially in the age of instant communication and fast paced politics. Another part of the report claims that those polled were more willing to be accepting of same-sex marriage if they were familiar with the issue (I.E.) know or are friends with some who is gay.

This ‘familiarity’ with the issue can be transcended into the realm of democratic defects. If people are made familiar with the particular shortcomings of our Constitution, it is possible a shift in public opinion as drastic as this one could occur. Of course being familiar with an idea and a person are two separate things, but the principle remains the same- if people are enlightened to the issue, they are more willing to accept the reality of it.

The changes that could come about from familiarizing people with their democratic rights could help to fix situations like the inequality in representation in the Senate. If we were to take the time out to educate people on how the Senate works and how it has effectively dissolved the voice of a majority of the American public, that same majority along with a group of sympathetic voters from the minority, an agreement on an amendment to either design the Senate to have a number of representatives that are proportionate with its people could be implemented; maybe even a complete abolition of the Senate itself, would be called for.

A process which allows for the opinions and views of a minority to be taken into account, one that strives for a consensus among a broad range of political leaders instead of the simply majority could ultimately lead to a healthier and more confident electorate in regards to how their democracy functions. The Electoral College can also be fixed to be more representative of the people instead of the artificial beings that are States.

Incremental steps would most likely be the way to go, seeing that most political leaders, especially from the smaller states, would be unwilling to abandon an institution that protects their influence. An amendment to make the Electoral votes proportionate with a state’s population could help protect the institution of political equality and dissolve future political crises.

If the electorate is made aware that by abandoning the Electoral college that their vote would actually mean more, their opinions would probably sway. The way the system works as of now is that only those residing in ‘swing’ or competitive states have the ears of Presidential candidates. If it were adjusted the way Dahl proposes, an arrangement as such could enfranchise these forgotten voters in ‘safe’ states like New York, Texas, or California. It would reshape our country’s political dynamics and force our Presidents to make concessions, to compromise, and ultimately become more representative of the American people as a whole instead of representative of Ohio or Florida.

After examining these institutions and the possibilities of reform, it is safe to say that there is much more debate to be had between the public and its political leaders. It is exactly this type of dialogue that Robert Dahl had in mind when writing this book. If there is one thing Robert Dahl has to tell us, it’s that taking the American Constitution for granted is something we can’t afford to do. We must look at it through outside perspectives, dissect it, analyze it, and let it breathe.

What makes our Constitution great is not who wrote it. It is not who it belongs to. It is not what it has produced. Rather it is its ability to reflect the common goals and aspirations of contemporary America. It’s this potential for change that makes our Constitution something that should be valued. Its strength comes from those that it governs over, not from the results it produces. Through a reshaping of our political consciousness and an enlightenment of the American public, a Constitution can be shaped that could lead America to become a country that is more fairly representative of its people; that is, if we want it to be.

Adrian Tawfik says

Great article. Election reform is so essential for America because our greatest weakness is corruption and malfunction in government. We need to reform our system of picking leadership and the reforms should bend towards a better democracy. I agree completely with the author.

Michael Ossipoff says

Yes, it’s an excellent article.

As a practical matter, proposals for changing our national policies, including those involving government, and including those that require Constitutional amendment, are, of course, what party platforms are about.

Constitutional change proposals can be found in party platforms.

When we choose a party platform, and vote for the nominees of that party, we thereby are choosiing what kind of America we want.

I’ve often pointed our the following:

With our Plurlity voting system, the optimal strategy, when there are unacceptable candidates who could win, is to combine votes on the most winnable acceptable candidate.

If you’re a progressive (someone who wants a government that is humane, egalitarian, and who has high standards for ethics, honesty and non-corruption), then surely “acceptable” means “progressive”.

In that case, for you, Plurality’s strategy, when there are unacceptable candidates who could win, becomes:

Progresssives should combine their votes on the most winnable progressive.

The candidate of the Green Party U.S. (GPUS) is, by any standard of measurement, the most winnable progressive candidate.

So, voting for the Green nominee is the progressives’ optimal strategy in our Plurality elections.

I suggest that the GPUS platform offers what most people say that they want (but they don’t know it, because parties other than the Democrats and Republicans (the two right wings of the Republocrat Party) are banned from media coverage. I suggest that the GPUs platform offers to fix the things that everyone is complaining about. If only they knew that.

I further suggest that, if everyone would read a few platforms, and then vote in their own perceived best interest, then the transition to a Green government would begin in 2014, and be complete in 2016.

Relevant to the article that I’m commenting on, we could then expect the Constitutional changes offered in the GPUS platform.

Before I continue, I should add that how we vote is quite irrelevant if we don’t have a legitimate vote-count. The vote-count, and therefore our elections, and therefore our government, won’t be legitimate unless it’s results are verifiable, and verified. Therefore, project #1 must be for Americans to demand a verifiable, and therefore legitimate, vote-count to be in place before the 2014 elections. Without that, no reform of any kind is possible.

One thing that the GPUS, and pretty much all non-Republocrat parties agree on is the elimination of the electoral college, ad its replacement by a popiular vote, for electing presidesnts. I agree with that proposal.

I agree that the allocation of senators and representatives by state, in the way that it’s done, is highly undemocratic too.

Let me mention a few suggestions that I’d make for the Constitution, as regards government. I certainly don’t claim tha this is a complete Constitution proposal. Just a few suggstions.

Some of it is the same with what the GPUS platform proposes, some of it is similar, and some of it is different. Making these suggestions doesn’t in any way mean that I don’t completely support the GPUS platform. These are just my own suggetions.

Yes, eliminate the electoral college, and replace it with a popular vote fdor the president.

Seats for the sentate and house of representatives should be given one to each equal-size district, rather than being allocated by state. No more “apportionment”. No more allocation of seats to states. Just divide the nation into congressional districts, without regard to states.

Gerrymandering is ridiculous, and it’s astonishing that it’s tolerated. My suggestion: No more districting by officeholders’ whim. All districting should be by an automatic system with no human input.

In one of my first Democratcy Chronicles articles, I defined and proposed “Band-Rectangle districting”. I propose it now for the nation’s districting for house and sentate seats. Nationally, without regard to states.

Do we need a senate? My understanding is that the senate is the result of the Great [bad] Compromiise. If thats the sentate’s only purpose, then elliminate it. Just have one Congressional house, and call it simply “Congress”.

But I don’t claim to know whether the senate/house combinations serves a useful purpose. Is it desirable to have one house whose members serve for 4 years instead of 2, and to have a division of labor between two houses, wit the longer-term house dealing with the graver isues? I don’t know. My first impression is “No”. Just have one house, and call it “Congress”. That would be my suggestion, though I’m not completely sure that there isn’t some merit in two houses. But simplicity is important, and I much prefer the great simplicity of dividing the country into Congress districs,pure and simple, instead of separate divisions into house and senate districts. My suggestion then: One congressional house, called “Congress”–unless there’s some very important reason for having two houses.

The GPUS, and some other progressive parties, advocate proportional representation. I don’t strenuously object to that, but I myself prefer single-member districts, as we have now (but with Band-Rectangle districting instead of gerrymandering). I don’t perceive any need or desirability in having parties in Congress that aren’t popular enough to win election in a single-member district. Therefore, though I don’t strenuously object to proportional represntation, I don’t care for it either. Besides, proposing it amounts to asking the public to accept a change much bigger than just doing our single-winner electins in a better way.

Parliamentary government? I don’t think that any party platforms advocate that, and neither do I. Again, I wouldn’t _strenuously_ object to it, but why not let the public elect the chief executive (as we of course do now)?

It is argued that, in parliamentary government, the executive can be replaced at any time by parliament. But, with adequate power of recall, the public could replace any officeholder at any time on short notice too.

The president has too much power, and that problem has been increasing. Maybe parliamentary government avoid that, and, if that’s the only way to curb executive power, then it would be worth it. But maybe a better Constitution could accomplish that, while retaining public election of the chief executive.

I feel that the chief executive shouldn’t be a branch of government unto himself/herself, but, rather should just be someone who is in charge of carrying out Congress’s policies, under close supervision by Congress.

I don’t like one person having so much power at all. Maybe, instead, have an Executive Committee instead of a president? Or maybe let all of Congress be that Executive Committee. That sounds like parliamentary government. It seems to me that there’d be very little responsibility that would have to be given to one particular person. Maybe just for a very few, strictly circumscribed, precisely-specified matters that require instant action.

So, even if the public elect a single-executive, that doesn’t mean that s/he should be a “branch of government”, or have the full executive power. S/he should only be empowered for a few specific immediate actions, where there isn’t time for a collective Executive Committee decision.

With the quick-decisions executive having as little power as I’d like him/her to have, there’d be nothing wrong with Congress, or its Executive Committee, chosing him/her. So I wouldn’t oppose parliamentary government, though, in principle, I like the idea of public choice of all government officholders.

Maybe the public, as a whole, should have the power to amend the Constitution, with some Constitutionall-specified supermajority and waiting-period.

Obviously the public should have full, easily accessed, powers of initiative and recall. That’s something that all of the non-Republocrat party platforms seem to agree on.

Constitutional amendment initiatives should merely have a supermajority requirement, and probably a waiting period, to avoid sudden emotional mistakes.

But the easiest way to get a better Constitution is by voting Green, and getting their comprehensive improvements for America, which would include a better Constitution, better government, better voting system, etc.

Speaking of voting system, I’d like to add that I suggest that there should be a national voting system, and it should be Woodall’s method, as I’ve previously defined it here.

The definition is brief, and so I’ll repeat it here. It starts with a definition of Instant Runoff (IRV), which uses rank balloting:

IRV:

Repeatedly, cross off or delete from the rankings the candidate who currently tops the fewest rankings.

(of course the winner is the last-remainin un-deleted canddate)

[end of IRV definition]

Woodall:

Do IRV till only one member of the Smith set remains un-deleted. Elect hir.

[end of Woodall definition]

The smith set:

The Smith set is the smallest set of candidates who each beat every candidate outside the set.

X beats Y if more voters rank X over Y than rank Y over X.

[end of Smith set definition]

A slightly more simply-defned, but not quite as choosy among the Smith set, method is Benham:

Benham:

Do IRV till there is one un-eliminated candidate who beats each of the other un-elmiinated candidates.

[end of Benham definition]

Woodall is better, because it’s more particular which Smith set member it chooses.

I recommend Woodall for all political voting, including the election of the president, or other, lower-powered, chief executive, and for members of Congress, in single-member districts.

Of course I also recommend Woodall for multi-alternative Initiatives and Referenda.

Michael Ossipoff

Michael Ossipoff says

I’d just like to add that maybe any directly publicly elected quick-decision executive would have too much power. What if s/he opposes Congress’ policies? How much sense would it then make for hir to be empowered to make quick decisions, including emergency decisions, for Congress? A policy-opposition between hir and Congress could result in inefficiency and too much power to one person.

Therefore, maybe parliamentary government, would be better, with Congress choosing its quick-decision person.

And the word “Congress” implies a branch of the government in the presidential system. Therefore, if we changed to the parliamentary system, we wouldn’t really have a Congress. We’d then have a Parliament instead. I like that. A new name for our new government’s decisionmaking body: Parliament.

My suggestiion, then, is a Parliament, elected in single-member districts, with equal-population district lines drawn by Band-Rectangle districting, without regard to states, and with the winners chosen by Woodall’s method, a rank-balloting voting system.

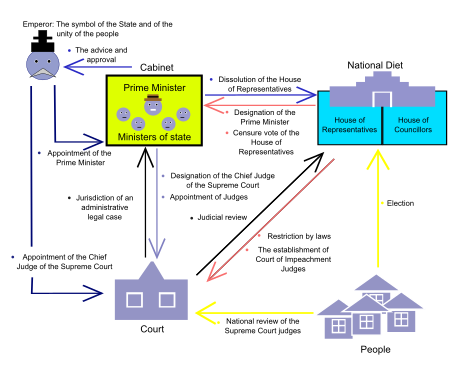

And, for making quick decisions (including emergencies), when there isn’t time for a Parliamentary decision, Parliament would choose a quick-decision person. I don’t know what s/he should be called. “Prime Minister” sounds too powerful.

Michael Ossipoff

Michael Ossipoff says

It was misleading for me to speak of just “a quick decision person” in parliamentary government. Of course the experience in parliamentary ountries is that the day-to-day running of a country requires the appointment of a whole government of ministers and their appointees, co-ordinated overall on short-notice by a prime-minister. …of course with the whole government replaceable by Parliament.