“You cannot tell a hungry child that you gave him food yesterday.”1

Reality – a word of our everyday language – escapes a definition. It appears impalpable, indefinite, undefined. Case in point, the nature of reality has been part of table discussions, where sides take place into considering reality to be relative or considering it absolute. Some say the experiencer defines what reality is, some say that reality is what it is irrespective of what the experiencer thinks about it.

Now, when the need to define reality arises – in any side we find ourselves in – we need facts. Yet, outlining the facts we need is not necessarily clear, as facts – for instance – could be subject to the language used when voicing them.

El pan tiene sonido de disparo

cuando una boca hambrienta lo pronuncia2

This need for facts has steered specific standards to be used when defining them. One of these standards being verifiability: to ascertain the truth or correctness of, as by examination, research, or comparison. We cognize sentences without worrying much as to how they are verified, understanding them because we recognize the words in them and the grammatical structure of the sentence as a whole. We come to question their verifiability when there’s an unusual combination of words.3

Another of the standards we need to determine facts is reliability: yielding the same or compatible results in different clinical experiments or statistical trials.

Tiene el sonido igual que un golpe claro

que claridad anuncia,

el pan, el pan4

In order to do this, we need to be aware of any indifference to facts, of any failure to reference works or investigating directly. Otherwise, we fall prey to fictions that are often central to an unreliable argument and its conclusions, which are seldom revised albeit the continuous accumulation of new facts and insights.5

Probability becomes another determining standard. It is “the measure of the likeliness that an event will occur. The higher the probability of an event, the more certain we are that the event will occur.”

El pan, antes que pan fue trigo airado6

Plausibility – a fourth standard – makes facts go through a credibility test, as plausible means “possibly true : believable or realistic.”

fue campo y sol, fue lluvia y tierra arada

fue la mano y la hoz y fue un dorado sudor

de piel quemada,

el pan, el pan7

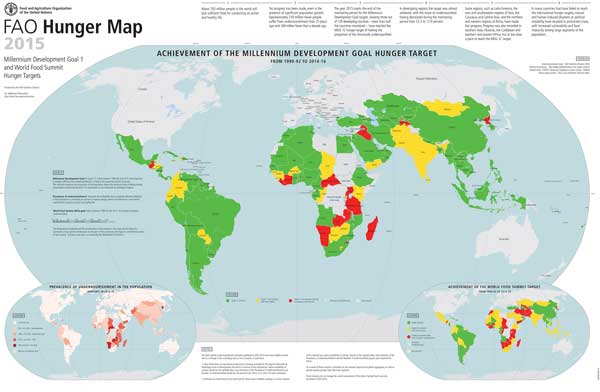

Albeit absolutes seem to appear before us when we test facts against reality, we need to incessantly reexamine what we call facts. Because then again, what is reality? Some say that reality is what it is irrespective of what the experiencer thinks about it, some say the experiencer defines what reality is. “About 793 million people in the world still lack sufficient food for conducting and active and healthy lifestyle.”8

LINKS:

- Zimbabwean proverb

- Elisa Serna–Jesús López Pacheco, “El pan”

- Verifiability

- Elisa Serna–Jesús López Pacheco, “El pan”

- Distinguishing Science and Pseudoscience

- Elisa Serna–Jesús López Pacheco, “El pan”

- Ibid

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “Hunger Map 2015”

Merlene Castillo says

Your topics are very interesting Ms. Ortega. Thank you for sharing.