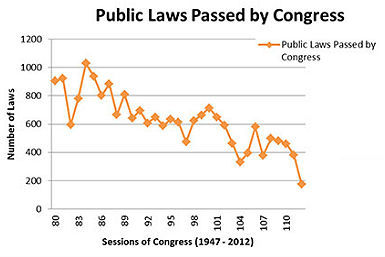

From 1947-49, the Republicans were able to gather a large majority in the House of Representatives at the peak of Democratic legislative success. The New Deal, Truman’s Fair Deal, and the recent military success in World War II, while providing the Democrats the ability to alter the landscape of American society, put a target on their backs. The Republicans were adamant in opposing any Truman/Democratic policy, and in so doing, passed a record low of 906 bills in those two years becoming known as the “do-nothing” Congress. While this was a particularly mercurial time in the United States’ history, it nonetheless provides a pertinent analogy to the subsequent research.

The 112th Congress (’08-’12) passed barely a third of the laws passed than the infamous do-nothing Congress, 333 to be exact making it by far the least productive Congress in history as well as the Congress with the lowest approval rating (with exception to the current Congress). So, how does it comport that in the 2012 mid-term elections, the American people nearly reelected 90% of incumbents for both the House of Representatives and the Senate?

When Rasmussen Reports came out with its latest Congressional performance poll a week before the 2014 mid-term elections, only 8% of the American people felt that Congress was either doing a ‘’good’’ or ‘’excellent job’’.

Yet, 90% of incumbents are again projected to win back their seats. This examples reflects the critical importance of the subject of political participation and why its malaise has contributed to a moribund on the issues they have held so much importance on.

This is not simply targeting political participation, rather it is identifying the core reasons democracy in the United States is in a malaise and has prevaricated action on plaguing issues until its effect becomes imminent to the individual. The causes are psychological, institutionally based, and have weaved its way permanently into our culture.

Citizen Inaction?

Thousands of years ago when philosophy flowed from the rawest of human senses, the act of community involvement and consolidation to contribute in the betterment and progression of society became foundational in the success of the ancient Greeks. As Aristotle wrote, “All persons alike should share in the government to the utmost.’’ The salience of daily citizenry in democracy was revered in ancient Greece; in fact, the word ‘’idiot’’ began as a term that defined those that were incapable or indifferent towards immersing themselves in civic life. The United States, on the other hand, was a society born on the principles of revolution, democracy, and anti-establishment fervor.

Unlike ancient Greece, it was predicated on the ideas of enlightened philosophers that created a foundation that would allow society to gradually adjust the landscape of laws to the tune of each generation. It was this, however, that put the onus on the citizenry to utilize their power of daily citizenship in order to progress society through daily democracy. As Thomas Jefferson wrote, “If a nation expects to be ignorant and free in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be.”

These two anecdotes encapsulate and highlight not just the privilege and value of civic engagement, but the question that imbues this topic. In ancient Greece, those who were reticent and indifferent were few and far between because life was egalitarian; life’s meaning rose from the most basic tasks and interactions. This made the “polity” salient in their lives; they understood the value that could come out of determining their own society, and because so, it was predominantly out of volunteer seclusion that they removed themselves from civic engagement.

In the United States, especially as capitalism consumed people with alternative interests and priorities, the American people gradually crawled into a more reclusive, private sanctuary. As the Civil Rights, woman’s suffragist, labor, environmental, and war movements eventually foisted itself onto the political establishment, there became a growing aura of entitlement- as if democracy would take care of itself. As myriad critical issues have foisted its way into 21st century society, the lack of energy in political movements and advocacy in the United States have been historically unique.

With an 8% of approval of Congress, 59% of people that believe the recently elected GOP Congress would likely be a disappointment, 70% of Americans believing the federal government should limit the release of greenhouse gases, 83% of Americans supporting lowering the interest of student loans, 60% of Americans wanting more government regulation of Wall St., and a majority of Americans supporting a medical care for all system, government has remained in a stalemate- unwilling to pass such laws. This would not be so disconcerting if it wasn’t for the dismal approval ratings that reflect people’s growing contempt for their government. Without the expression of the American citizenry through voter participation, democracy persists while discontent brews.

Increasingly today, the American youth are feeling powerless. This is reflected in their apathy, reluctance, and all together discontent with politics in general. Presidential elections in America extrapolates-through media’s interpretation of such- a certain verve among Americans whereby they feel they are participating in a national sport. There is a primary distinction between this, and the values bestowed by Aristotle and Thomas Jefferson in the responsibility to contribute to society as a whole through the political process.

Prospect of Intentional Youth Seclusion

The mid-term elections, according to polls conducted by “The Upshot” wing of the New York Times, showed a substantially lower voter interest than four years ago. In addition, only 12% of the youth made up the electorate in this mid term election while 37% were made up by those 65+. The indolent political participation among the youth in the United States has a corrosive effect on democracy. The youth have a plethora of pervasive excuses for not voting: “Unable to make a difference, one vote doesn’t matter, money determines everything, or the system is too corrupt” make up the common thread of seclusion in the youth. What they aren’t realizing, or perhaps aren’t feeling passionate enough about, is that their votes en masse have a profound effect. As the 2012 election exemplified, if Mitt Romney would have split the youth vote with Barack Obama, he would have cruised to victory. Obama won the youth vote 67-30% and further, the youth made up 19% of the electorate.

Civic withdrawal has become the norm in the United States according to author of the book Soul Of a Citizen by Paul Rogat Loeb. Loeb relates this to a similar psychology of people who suffer from severe depression. As he states, “Depressed people have become so convinced that the causes of their difficulties are permanent and pervasive, inextricably linked to their personal feelings. This master narrative of their lives excuse inaction; it provides a rationale for remaining helpless.” (SOC, Pg. 25). With the advent of unfettered capitalism controlling and determining the political culture in the United States, citizens have become more and more detached from their own democracy.

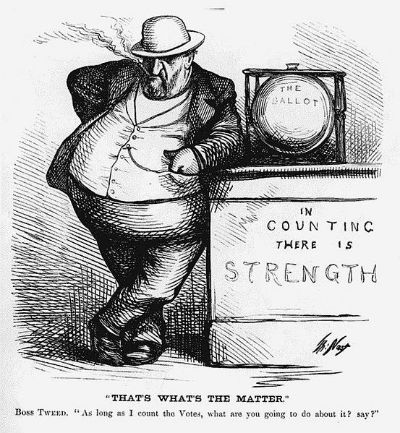

The common excuses of “our vote doesn’t matter”, “politics is too corrupt”, etc. all stem from the fact that citizens don’t feel they can exert the influence that those with large monetary wealth do. In an era of history where inequality is as high as it was during the Gilded Age, this feeling is only natural. There a plethora of reasons that have stemmed from the core root cause which, in lieu of the omnipresence of money in politics, is unfettered capitalism. But, unfettered capitalism isn’t akin to having an authoritarian leader at the reign, having censorship laws, or a completely intractable political system. The American people have an excuse to not be political participants; but not a justification.

Leave a Reply