While Iraq as a country was created only after World War I, there few places that can claim a more important role in the story of humanity. Known in ancient times as Mesopotamia, Iraq was central to the development of agriculture-based society as part of the fertile crescent in the ‘cradle of civilization’. For thousands of years, my family was part of this history. We are a small part of the diaspora of Jews made refugees during the last century. This is a story of how the discovery of a few documents have brought light to our forgotten part of world history and reawakened the passions of an ancient community that was violently displaced from its ancestral land, fully aware it was never going to return.

Journey Through Time

Abraham, the first Jew and father of monotheism, was born in Iraq. While Abraham famously left Iraq for Israel, large numbers of his offspring returned to Iraq as slaves of Nebuchadnezzar II’s Neo-Babylonian Empire around 722 B.C., after the destruction of the First Temple of Jerusalem. Jews lived in Iraq for the next 2,700 years, the bulk of recorded human history.

It was only in the epic violence of the 20th century that the ancient social structures necessary for peace permanently fell apart. Amid the chaos of World War I, the Ottoman Empire collapsed and its province of Iraq was awarded to England. What followed was a short and violent period of colonialism that forever changed the country and the region. Short-sighted divide and rule tactics perfected through centuries of British colonialism fed religious extremism during a period of rising violence between Jews and Muslims in Palestine. At the same time, Adolf Hitler’s ascendant Nazi Party in Germany fed anti-Semitic propaganda to the Arab world’s independence movements to weaken British and French control.

When Iraq gained nominal independence from the United Kingdom in 1932, laws were immediately passed prohibiting Jews from activities like holding senior government jobs and oppressive quota systems were established at universities. The founding of the modern state of Israel after World War II led to an unprecedented outburst of anti-Semitic violence including a series of repressive laws, arrests, and public executions. In this period, my own grandfather was imprisoned in Baghdad.

Finally, a law passed in 1950 created a year-long break in the longtime ban on Jewish emigration from Iraq. By the end of a year of increasing violence, the vast bulk of the Jewish population, including my family, registered to leave, only to learn after that their Iraqi citizenship was revoked and their property confiscated by the government.

In Iraq and other Arab nations, a monumental and permanent flight of ancient Jewish communities was completed within a few years – not unlike the exodus of Jews from continental Europe after the Holocaust only a few years earlier. Out of the roughly 800,000 Jews in the Arab world in 1948, only 6,500 are left today. In 1948, there were roughly 150,000 Iraqi-Jews including up to a quarter of Baghdad’s population. By 2012, there were as few as five Jews known to live in the whole country.

There has been a diminishing connection between those of us with roots in the Iraqi Jewish community and what might be called ‘the home country’. The Jewish-Iraqi dialect of Arabic (a mixture of Arabic with Hebrew, French, English and Turkish) is slowly fading away. Most of the older generation has long-ago abandoned hopes of returning to Iraq in their lifetimes and the new generation has little remaining connection to a country they have never been able to safely visit.

The World Turns Again

In March of 2003, the United States military invaded Iraq and toppled the government. In the televised “shock-and-awe” bombing campaign that began the American invasion, major targets like the headquarters of Saddam Hussein’s notoriously violent secret police, the Mukhabarat, were destroyed in an attempt to decapitate the regime. Not long after U.S. forces entered Baghdad, a small team was sent to the destroyed Mukhabarat headquarters to investigate rumors of an archive of Iraqi intelligence about Israel.

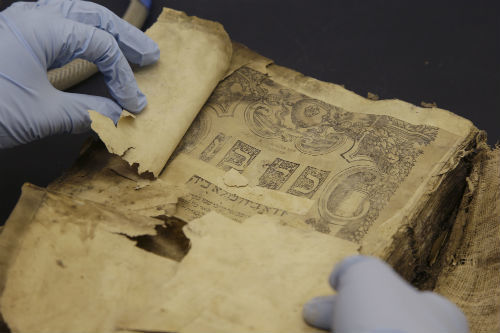

Inside the bombed-out building’s basement, now flooded in river water, the team found a trove of Torah scrolls, religious items, documents, and books written in Hebrew, Arabic, Judeo-Arabic, and English. Knowing the material would not survive underwater, the American team removed what they could and cleverly laid out the entire collection on the streets of sun-baked Baghdad to dry.

It was already known that previous Iraqi governments had confiscated large amounts of property from Jews during previous decades and the American team was quick to realize that this was what they had discovered. The still deteriorating collection was hastily loaned to the U.S. by the newly installed post-Saddam government and shipped to Texas for restoration. However, the nature of the loan was immediately questioned by Iraqi factions worried of a new wave of colonial-era looting. A diplomatic spat lasting several years ensued, with Iraq refusing to relinquish permanent control of the documents.

It took a while for the story of the archive to reach its real owners in the Iraqi-Jewish community but the discovery was eventually made public. As it happens, a portion of the archive found in Saddam’s intelligence headquarters was taken from the Meir Tweg Synagogue founded by my great-great uncle, Meir Tweg, and managed by my great-grandfather, Dahud, born in Baghdad in 1873. The confiscation of Jewish property was relatively common during the exodus and, in 1984, years after the Jews had fled, Saddam’s henchmen raided the Meir Tweg Synagogue and stole everything they could.

The controversy eventually became so politically heated that a unanimous vote was held in the U.S. Senate on a resolution urging the State Department to reconsider returning the artifacts to Iraq. Finally, in May of 2014, the newly elected Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi agreed to allow the archive to stay in the U.S. for an undefined extended period. Jewish organizations are now working for permission to permanently return the school records and other personal documents to individuals and to donate the religious items to Iraqi Jewish synagogues.

My family was later able to visit the collection at a National Archives exhibit. Highlights included a Hebrew Bible from 1568 Venice and a Babylonian Talmud from 1793. There were also photograph displays with school records and water-damaged Iraqi government edicts describing new regulations and limitations for Jews. All of the archived materials can be found on the National Archives website at ija.archives.gov.

The Meir Tweg Synagogue of Baghdad once served as a Jewish school and community center, in addition to being a place of worship. To find something to compare it to today, you have to leave the country.

BONUS IMAGE GALLERY:

An archive of photos from the Meir Tweg Synagogue in Baghdad taken by Harold Rhode unless otherwise noted:

Dr. K. says

Thank You Adrian. It’s good that people know these are available to discover and/or rediscover. It helps link a lost connection and re-connect with their family and community through these community heirlooms.

Adrian Tawfik says

Thanks Dr. K! Much appreciated!

Dan Tawfik says

This was so exciting to read again. Curious what extended period means!