By Monica Angelina Snowball and David Anderson

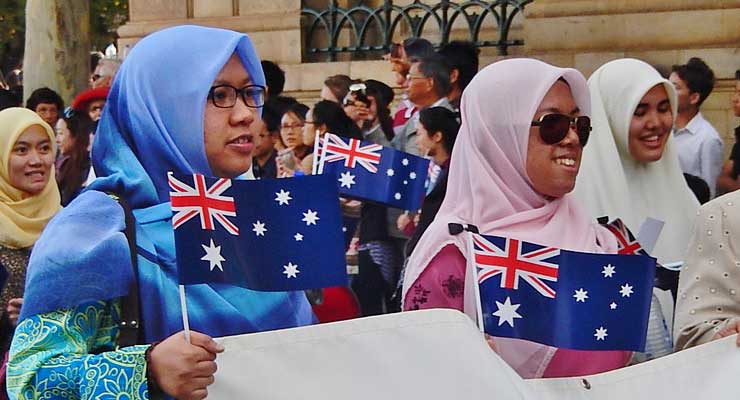

Australia is a nation similar to the U.S. in many respects; British colonized, sort of English speaking, of comparable geographic size and immigrant makeup. Also similar: rising xenophobia and the “othering” of Muslims. Australia’s Islamaphobia is as controversial as it is in US.

A recent Q&A episode on the Australian Broadcasting Channel featured a young Muslim activist/engineer, Yassmin Abdel-Magied, arguing the US immigration ban and feminism in Islam, went head to head with far-right State Senator Jacqui Lambie. The debate further electrified the issue in Australia.

In the now viral debate, Ms. Abdel-Magied asserted that policies which bar foreigners of a certain faith or nationality are acts of prejudice. She spoke about the judgments and misconceptions made by Australians due to a lack of understanding of Islam, and explained that culture is very separate from religion.

President Trump’s now famous “Muslim Ban” is also a contentious issue in Australia, where Islamophobia has been gaining traction for many years. The ban, subsequently struck down in the US by the Federal 9th Circuit Court, (now resurrected) was met with a positive reception in Australia, but was divisive between Muslims and many non-Muslims. The US court held “individuals must be free from discrimination” – a hard concept to argue against.

Senator Lambie backed Trump, saying he had every right to bar nationalities to keep America safer, just before raising her voice at Abdel Magied, telling her to “Stop playing the victim” and “Your ban got lifted, get over it.” It has subsequently been re-introduced in a slightly diluted form.

The lively discussion brings our attention to human rights and the freedom of religion in Australia. The latter right is contained in Article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, a treaty Australia ratified in 1980. Article 18 states that everyone has the freedom to choose their religious belief – or none – and practice accordingly. Furthermore, the treaty emphasizes that any discrimination hardened into law, like immigration law, officially hinders a sense of community and damages that right.

Ms Abdel-Magied, an immigrant who came to Australia as a child, compares her religion to other religions to elaborate why it is the most feminist of all. However, it is a basic human right to have the freedom to choose any religion without discrimination. Ms. Abdel Magied and fellow Muslims in Australia or the United States may not believe this right is currently protected or respected.

Politicians like Ms. Lambie argue that banning Muslims, and the much less numerous subset of believers in Sharia Law, will protect Australians from “terrorism”. Such an argument deserves an analysis of the causality of terrorism by the numbers. Does terrorism have more to do with the religion, or is it more of a cultural causation stemming from certain geographic regions?

We cannot deny the existence of Islamist attacks, but we need to understand that “terrorist” attacks are mostly from non-Muslims. According to the FBI, 94% of terrorist attacks carried out in the United States from 1980 to 2005 were by non-Muslims, a fact buttressed by the Canadian intelligence/research institution Global Research in a more recent article entitled “Non-Muslims carried out more than 90% of all terrorist attacks in the US.” This is not the impression we get from our media. Global Research further states that in Europe a similar dynamic occurs with over one thousand terrorist attacks in the past five years: less than 2% committed by Muslims.

Islamophobic “Othering” is very real in Australia. Othering relies on clichés and stereotypes such as hostility to non-Muslim culture, sexism, and being prone to violent behavior which is no way to build a community that has traditionally welcomed immigrants. It’s particularly hypocritical in countries populated by diverse immigrants and their descendants such as Australia and the US. Where Islam is seen as being oppressive to women, it is frequently the fault of culture rather than religion. Culture and religion are separate, as stated by Ms. Abdel Magied in the fiery debate.

Mr. Rhiyaad Kahn, formerly of the UN Association in Western Australia, said in an interview: “There is a section in the Quran titled Women and this was created because women were standing up for their rights during the Pagan period.” He goes on to state that the Quran explores inheritance rights, divorce, alimony, the details of a husband’s obligations to financially maintain his wife, and her sexual gratification. This chapter was created to enforce these rights for women and similar rights seem to be non-existent in other religious texts during this period of time. He further argues that Muslims do not wish to compare texts, but feel the need to do so in order to achieve equality.

Along with being similar societies with all the good; strong rule of law, secularism, and equality, the dark forces of mistaking religion for geographic culture, Islamophobia, and “othering” continue to divide and lessen the common goals of both nations.

Monica Angelina Snowball, L.L.B. (Perth, W.A.) and David Anderson, J.D., (N.Y.C.) are Australian and Australian-American lawyers/writers. They write on legal and political issues and have practiced human rights, gender, international, and criminal defense law in their respective cities.

Leave a Reply