When someone wins an election with fewer than half the votes, what do you think? Many would call this winner undeserving. After all, they didn’t get a majority.

You know how a majority works. Right? Maybe not. In the world of voting theory, A LOT is counterintuitive—including the concept of majority. So get a chair because you’ll need to get comfortable for this one.

An Introduction to Majority

Let’s get some terminology out of the way. There are at least three terms that get at the idea of majority when talking about voting.

Plurality. Plurality means having more first-preference votes than any other candidate but not necessarily more than half. Note that this is the concept of a plurality, which is different than the actual voting method, plurality voting. (Plurality voting is the seemingly-everywhere voting method that has us choose only our first-preference candidate.)

Absolute majority. An absolute majority means a candidate has received more than half the first-preference votes. It’s impossible to guarantee an absolute majority under any voting method when there are more than two candidates because that candidate will not always exist.

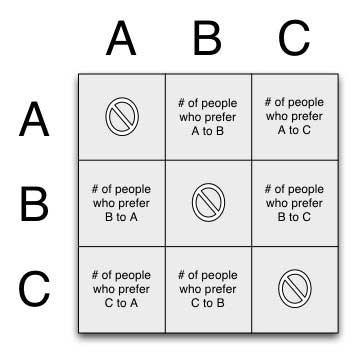

Condorcet winner. A Condorcet winner is a candidate who can beat every other candidate in a head-to-head race. Condorcet winners are typically determined using a ranked ballot, though you can also use information from scored ballots to simulate a Condorcet winner. If you have an absolute majority winner, then that person is also your Condorcet winner. If you have a Condorcet winner, there still may not necessarily be an absolute majority winner.

Not strange enough yet? A Condorcet winner also doesn’t always exist. The absence of this winner is called a cycle or a Condorcet paradox. Imagine candidates that interact like the game Rock-Paper-Scissors and you get the idea.

Finally, just for the heck of it, let’s toss in a multi-winner bonus concept for the end.

False (aka Manufactured) Majority. A false majority typically refers to entire legislatures. This is when a party gets more than half the seats yet they get fewer than half the votes. These peculiarities happen more than 40% of the time with winner-take-all systems. Winner-take-all systems are election systems that exclusively use single-winner districts when electing a legislature or parliament.

Does the concept of “majority” sound as straightforward now? The two ideas that sound intuitively nicer—absolute majority and Condorcet winner—don’t always exist and nobody seems to like a mere plurality winner. When there are more than two candidates, no voting method can guarantee an absolute majority or Condorcet winner.

But you say you have an example of a voting method that guarantees a majority? Using a runoff, you say? Let’s explore.

The Runoff and Majority

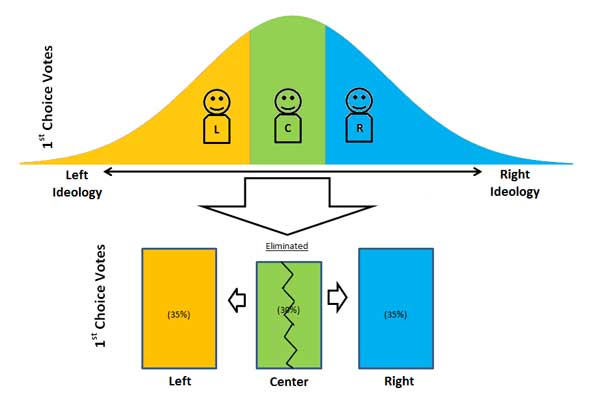

A runoff is regular choose-one plurality voting where the top two candidates go to the next round. If a candidate has more than half the votes in the first round, however, then there’s no runoff. The catch is that using plurality voting in the first round can eliminate a good candidate. It can do this by squeezing out the middle candidate, someone with strong consensus support. See the illustration below.

Normally you see just the plurality-voting results of the middle candidate. Plurality voting makes that middle candidate look bad: you only see the dismal vote total and dismiss the losing candidate as poor. But had voters provided you with more data, then you could have seen that they just eliminated the candidate who could beat everyone else head-to-head—the Condorcet winner.

What you actually saw was a candidate who lost in the first round because of an artificially low vote count. The first plurality voting round split the votes on either side of the moderate. Then you saw a runoff between the two candidates who in the first round split the vote on just one side of their political spectrum. And between those two remaining candidates, one candidate got an absolute majority.

That last part is what fools people.

Here’s the issue: you can always get an absolute majority winner when there are just two candidates. The problem is who you knock off to get to those last two candidates and whether one of the candidates you knocked off was actually someone you should have kept. The mere fact that you have two candidates left in the end is meaningless.

What about instant runoff voting (IRV)? Doesn’t it always guarantee a majority?

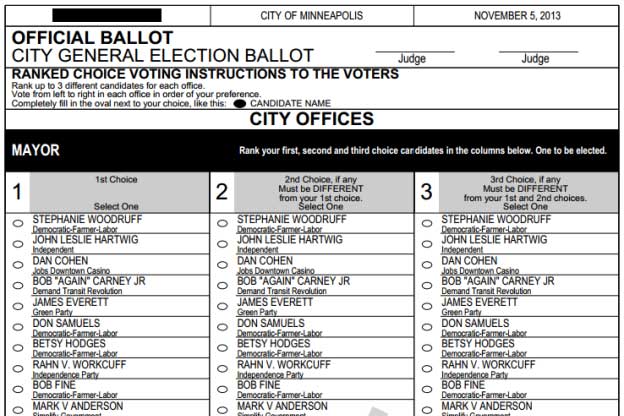

Instant Runoff Voting (aka Ranked Choice Voting) and Majority

IRV is a ranking method that simulates sequential runoffs. Using the runoff example above, it would have eliminated the same moderate candidate in the first round who could have beaten the other candidates head-to-head.

IRV’s “majority” is not only as artificial as a traditional runoff majority, but it also refers only to active ballots. This means IRV’s “majority” doesn’t consider ballots where voters didn’t get any of their preferred candidates to move to the final round. Rather, it only considers what a “majority” is out of the remaining active ballots. This effect is further exaggerated in jurisdictions that limit voters to three rankings.

So IRV’s “majority” isn’t very helpful. IRV can still eliminate good candidates, and its “majority” doesn’t refer to the original ballots. An IRV “majority”—like any voting method that knocks off candidates—is contrived.

What about a voting method that always picks the Condorcet winner when one exists? That is, it passes the Condorcet criterion. Let’s see.

What about a voting method that always picks the Condorcet winner when one exists? That is, it passes the Condorcet criterion. Let’s see.

Condorcet Winner

Recall that a Condorcet winner is someone who can beat every candidate head-to-head. But that winner isn’t always there. These Condorcet winners are less likely to exist in competitive elections with more candidates. A voting method could satisfy the Condorcet criterion (it always picks the Condorcet winner when one exists) and yet it could still make inferior decisions when those Condorcet winners weren’t there. And the same holds true with majority-focused methods in that they can make inferior decisions when an absolute majority winner doesn’t exist.

In some cases, however, picking an absolute majority winner or Condorcet winner may not be the best decision either. Here’s an example using scored utility values to show a point.

Key: Number of votes with this ballot: Candidate (Utility) > Candidate (Utility) > Candidate (Utility)

21,000: A(10)>B(9)>C(0)

10,000: B(10)>C(0)>A(0)

10,000: C(10)>B(9)>A(0)

Here, the Condorcet winner is A. That is, A can beat both B and C head-to-head. Yet, nearly half the voters really hate A. When you break down average utility values per candidate, you find this:

A: 5.1

B: 9.2

C: 2.4

While A was the Condorcet winner, the candidate who created the highest utility for voters was B. It’s not even close.

Methods that have you rank candidates (includes choose-one plurality) are called ordinal methods. But when we start talking about utility measures, there’s another category, called cardinal voting methods. Let’s look at cardinal methods now.

Majority In Cardinal Methods

Here’s another kicker: The concept of majority is even more peculiar in cardinal methods. Cardinal methods involve scoring on a scale. That could be a scale of 0-1, which is effectively approval voting or choosing as many candidates as you like. Or, the cardinal method could be a wider scale, like 0-9. If you have voters score each candidate that way with the winner being the candidate with the highest average, then you’re using score voting (a.k.a. range voting).

So what counts as a majority with one of these methods? Is an absolute majority a candidate with a score greater than one-half the maximum score? In that case, we could have two candidates with an absolute majority. Alternatively, if we made the total score value from all the candidates and made that the denominator instead of the ballot count, then candidates would seldom have more than half. (In practice, the convention is to use the ballot count rather than the score count when framing the results.) Yet another option is to translate the scores into rankings, but then we can lose information.

A candidate who has more than half the first-choice preferences doesn’t always exist. But when that candidate does exist, a voting method that always picks that candidate is said to pass the majority criterion.

But should the concept of majority even apply to cardinal methods given their focus is utility?

Majority Criterion

Here, we’ve got the same issue as before. On the face of it, it looks like this majority criterion makes sense. If someone is preferred most by more than half the electorate, then they should get elected, right? But when we go back to the Condorcet-winner example, the same idea holds to the majority criterion. That is, we can sometimes miss out on a winner who brings higher utility to the voters.

The idea that a voting method might not always pick an existing absolute majority winner is a common criticism against cardinal methods like approval and score voting. There are a couple considerations, however. First, as we noticed, an absolute majority winner or Condorcet winner isn’t necessarily the best winner. Second, even if that particular winner isn’t selected, popular cardinal methods are going to tend towards a high-utility winner, on average. So even in a worst-case scenario you’re still getting a reasonable result with the cardinal method.

Another consideration among cardinal methods is that if particular voters wanted to be tactical and force a maximum preference distinguishing their first-choice candidate, they could. Thus, they’d elect an absolute majority winner when it existed. Because of this flexibility, cardinal methods like approval and score voting are said to pass a “weak” majority criterion.

You’ve probably heard the phrase that democracy is two wolves and a sheep voting on what’s for dinner. That saying is provoking precisely because we assume that an absolute majority rather than a maximized utility will decide an election. Strangely, some critics use this idea to put cardinal methods in a catch-22. They complain when cardinal methods side with utility (the sheep). But at the same time they argue that everyone will vote tactically and side with the absolute majority. This reasoning implies that any decision a cardinal method makes is the wrong one, regardless of what that decision is—and even if an ordinal method would have picked the same person.

Let’s finish up by looking at the majority concept in large governing bodies.

The False Majority

False majorities occur when you deal with larger governing bodies. There are several ways to elect a larger body. For simplicity, here are two popular ways.

One option is that you can elect those seats in single-member geographic areas. This is called winner-take-all. This is what we do in the US. Our winner-take-all voting method of choice is choose-one plurality voting.

A second option is to take that entire governing body and elect them at-large without respect to geography. And as you elect them, you can use a proportional voting method. That is, the voting method elects people to office in proportion to the number of voters who support them. Proportional methods are mostly an alien concept to the US but are used in most other countries around the world.

Here’s where a false majority comes in. When a party gets more than half the seats despite getting fewer than half the votes, that’s a false majority.

Scholars like Douglas Amy have pointed out that winner-take-all systems elect a false majority close to half the time. Imagine the wrong party controlling an entire nation’s government close to half the time. Not good.

The prevalence of false majorities isn’t a figure regularly calculated in the US, but it is commonly measured in Canada. A recent Canadian election had one party take more than half the seats despite the party getting less than 40% of the vote. That’s crazy.

You might look at that crazy outcome and think, “Wow, Canada must gerrymander its districts just like we do!” Indeed, gerrymandering directly exacerbates the false majority effect. But you’d be wrong to call out Canada on gerrymandering. Canada has used independent commissions for its districts since 1964. Yet, it still gets this crazy result.

This apparently inherent reality to single-winner districts should act as a lesson to those who see independent redistricting as a solution for distorted legislatures. It’s possible that using a different single-winner voting method could diminish this distortion. But on the surface, the core problem appears to be electing legislators from individual districts. Counting only single winners within each district acts as a sort of sloppy sampling from the nation as a whole. So you end up with a mangled end product—a highly disproportional governing body.

The more consistent way to make sure you don’t have a false majority is to elect the governing body at-large and elect seats proportionately. Douglas Amy in his book Real Choices/ New Voices pointed out that false majorities occur less than 10% of the time with countries that use proportional representation. Less than 10% is a big difference compared to close to half with winner-take-all.

So instead of independent redistricting commissions, the more direct reform would be to implement proportional representation.

Putting the Majority Myth To Rest

That’s how the majority concept really works with voting. Plurality voting—unsurprisingly—creates serious issues. And actual or simulated runoffs don’t provide a solution either. Cardinal methods, on the other hand, target a different metric altogether. While it can have overlap with majority ideas, it can’t achieve the impossible either. No method classification or individual voting method can make guarantees about finding appealing types of majorities.

Now you’re prepared when someone tells you that their litmus test for a voting method is that it always gets an absolute majority. Tell them they’re in for a never-ending search.

Voting methods and the majority concept have a lot of nuance. This means that if the “majority winner” isn’t elected, it may not be the end of the world. In practice, both an absolute majority winner and a high-utility winner are going to be pretty reasonable. You just have to mind who you elect when that absolute majority or Condorcet winner doesn’t exist. Also consider that, in contrast, there will always be a candidate who has the most utility (or ties).

Conclusion Majority Illusion

Of course, if a candidate gets elected that is both not preferred by a majority and has a relatively low utility to voters, then you’ve got a problem. A voting method that regularly makes that bad decision is not a voting method you want.

Also see our entire section called Voting Methods Central.

Leave a Reply