Big win in Maryland partisan gerrymandering case could lead to a new path for real reform

From NYU’s Brennan Center:

Partisan gerrymandering has long befuddled the courts. Although judges have recognized the harm of the practice, they have been unable to agree on a standard for policing it. But for the second time in a year, a partisan-gerrymandering challenge has cleared a critical hurdle.

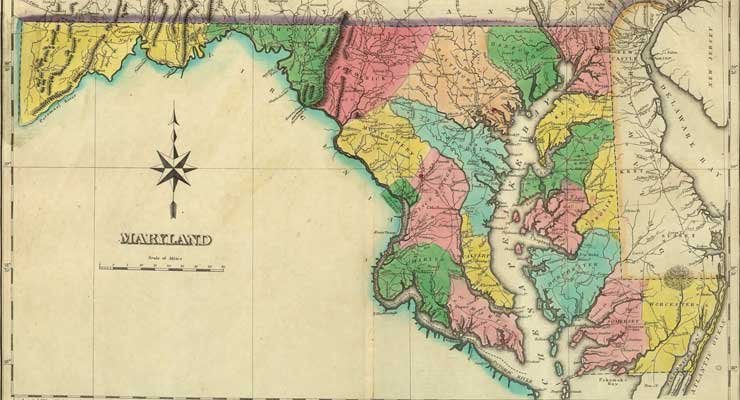

Earlier this week, voters challenging the drawing of Maryland’s 2011 congressional map got the green light to proceed with their First Amendment claim when a panel of three federal judges voted 2-1 to deny a motion to dismiss from Maryland’s attorney general. The voters — plaintiffs in the long-running case Shapiro v. McManus — will now be able to conduct discovery in preparation for a trial. The victory gives new momentum to a case that, along with a partisan-gerrymandering challenge pending in Wisconsin, could soon be headed for the U.S. Supreme Court, where the Justices will have their first opportunity in more than a decade to decide whether partisan gerrymandering violates the Constitution.

The panel’s opinion focuses on the legal sufficiency of the plaintiffs’ complaint, which challenges the 2011 congressional redistricting plan enacted by the Maryland General Assembly. The plaintiffs alleged the legislature deliberately used information about voters’ partisan affiliations and voting histories to flip Maryland’s Sixth District from an otherwise reliably Republican stronghold into a safe Democratic seat, all in a successful attempt to punish Republican voters for casting ballots for their party’s candidates. On those facts, the panel ruled, the plaintiffs stated a claim that could go to trial, endorsing the plaintiffs’ theory that these kinds of districting machinations violate the First Amendment.

The First Amendment problem with Maryland’s redistricting, the panel explained, was that it diluted the plaintiffs’ votes — that is, made their votes less powerful than other voters’ — by placing them in districts where they were outnumbered and repeatedly outvoted by Democrats, and did so simply because the plaintiffs had voted Republican in the past. That dilution was an example — albeit a novel one — of the kind of retaliation for political speech and association that the First Amendment bars.

A First Amendment theory of partisan gerrymandering has been a kind of holy grail for redistricting plaintiffs ever since Justice Anthony Kennedy suggested the possibility in his concurrence to 2004’s Vieth v. Jubelirer. In addition to perhaps better describing the harms caused by partisan gerrymandering, the First Amendment might offer a detour around the judicial gridlock that’s snarled prior attempts to treat it like a Fourteenth Amendment problem. That was precisely the perspective of the Shapiro panel, which pivoted off Justice Kennedy’s concurrence to take a new approach to the issue.

The panel defined its partisan gerrymandering standard as a three-part test. According to the court, to state a First Amendment claim, plaintiffs have to allege three things: First, that the mapmakers intended to retaliate against them for their political expression or affiliation (intent); second, that the new map in fact harmed them (injury); and third, that the harm couldn’t have arisen absent the mapmakers’ retaliatory agenda (causation). The core allegations of plaintiffs’ complaint, the panel concluded, were enough to pass this test at the pleading stage.

Despite the win for the plaintiffs, the panel did make efforts to limit the reach of its decision to address the Supreme Court’s concerns that partisan-gerrymandering litigation could drag courts into every redistricting dispute. The panel emphasized three limits to its test: First, that partisan mapmaking is only unconstitutional if it is retaliatory; second, that plaintiffs have to provide objective evidence of the mapmakers’ bad intent; and third, that the plaintiffs must be harmed in a “palpable and concrete” way.

While this week’s decision is a significant victory for those fighting partisan-redistricting abuses, a lot remains to be resolved. The plaintiffs still will have to carry the day at trial in order to win their case. And the Supreme Court ultimately will need to decide if this is the case that establishes — at long last — a workable standard for policing partisan-gerrymandering abuses. As the dissent penned by U.S. District Judge James K. Bredar suggests, even judges (or Justices) generally convinced that partisan gerrymandering is unconstitutional might have doubts regarding whether the majority’s test is the best way to police it. Nevertheless, the panel’s ruling is a substantial step forward in a case that’s encouraging the courts to explore novel and innovative approaches to a serious, age-old problem.

Leave a Reply