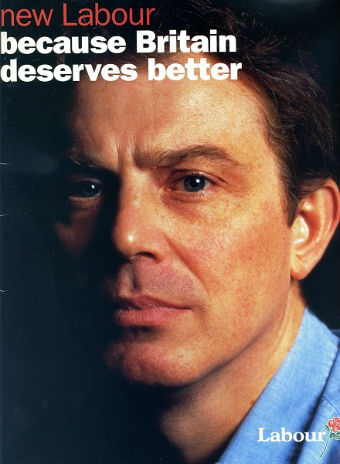

In the wake of a political landscape transformed under Thatcherism and a Labour party languishing in the abyss, the new British Labour party was going to have to rebrand itself to revitalize the nation around its brand. As modernization, globalization, and capitalist economics became resoundingly popular after the Thatcher and Major years, Labour understood its appeal was antiquated. Perhaps their ideologies weren’t, and perhaps it was a political capitulation starting with Neil Kinnock and implemented under Blair. Be that as it may, New Labour and Tony Blair were what thrusted the Labour party back into prominence. One could very well argue, however, that New Labour was little more than a congenial version of the Conservative party. A key aspect to be explored in this essay is if New Labour was willing to sacrifice the values of the Labour party for the opportunity of political power. Or perhaps that they were merely trying to adjust the Labour party to a modern economy that relied on centre left/business friendly economic policies. New Labour did have its share of disconnected ideas and seemingly close ties to remnants of Thatcerism more than democratic socialism. Despite this, one cannot ignore that New Labour achieved historic success under its revamped policies, and therefore New Labour was far more than a set of disconnected ideas, it was a centre-left revolution.

New Labour’s reforms targeted both the organizational structure of the party and its ideological platform with the ultimate goal of making the Labour party electable again. Kinnock initiated a gradual shift from Old Labour nationalization to a more contemporaneous version of European democracy1. This purposefully purged Labour of its socialist ties and led to a reassessment of key philosophical ideas more closely associated with a moderate economic perspective. The Thatcher government had replaced Keynesian economics with neo-liberalism, and New Labour went right along with it. This is not to say that neo-liberalism had a popular consensus in the country, but nonetheless Conservatives had been associated with the party of big ideas and the only way the Labour party envisioned itself achieving that same status was to adopt economic policies that were focused on growth and modernization.

New Labour’s reforms targeted both the organizational structure of the party and its ideological platform with the ultimate goal of making the Labour party electable again. Kinnock initiated a gradual shift from Old Labour nationalization to a more contemporaneous version of European democracy1. This purposefully purged Labour of its socialist ties and led to a reassessment of key philosophical ideas more closely associated with a moderate economic perspective. The Thatcher government had replaced Keynesian economics with neo-liberalism, and New Labour went right along with it. This is not to say that neo-liberalism had a popular consensus in the country, but nonetheless Conservatives had been associated with the party of big ideas and the only way the Labour party envisioned itself achieving that same status was to adopt economic policies that were focused on growth and modernization.

The revising of Clause IV provided the formal impetus of New Labour, and the abrogation of the old. As Blair’s charisma and political savvy brought him to the premiership, he sought to implement the renewed values of New Labour to the forefront of British politics. Blair had believed that Labour’s ideology was outdated and too constricted to socialist thinking- especially in terms of state ownership2. The values New Labour adopted to cater to Blair’s vision for Labour prominence focused on: equality, protection of the vulnerable, freedom as autonomy, no rights without responsibilities, no authority without democracy, cosmopolitan pluralism, and philosophic conservatism3. In addition, New Labour extracted ideas concerning private choice, the ‘’furtherance of individual interests’’, and a concern for citizens in part by the welfare state but mainly through the exercise of personal responsibility4.

Blair’s rebranding of the party not only shifted its ideologies slightly towards the center, but it became a party that attracted business. No longer was the Labour party at the hip of unions. Instead, it became a party of and for business, a party that was rational and sensible, not extremist, and not reckless5. Some have disregarded New Labour as an ideology at all, and could probably further make the case from this view that it was nothing more than disconnected ideas enmeshed to gain an effective electoral brand. As one will see with Blair’s policies as Prime Minister, New Labour may have maintained ideas that were ambiguous and disconnected, but it certainly took on an ideology and project of its own.

Blair set out with four broad policy objectives: a dynamic knowledge based economy founded on individual empowerment and opportunity where governments enable not command, a strong civil society enshrining rights and responsibilities where the government is a partner to strong communities, a modern government based on partnership and decentralization where democracy is suited to the modern age, and a foreign policy based on international cooperation6. Essentially, the Labour party had become a party focused on a more modern version of social democracy firmly based in human and economic capital. In economic terms, the world had expanded significantly, with global trade competition becoming more intense. Blair had identified the cornerstones of the new global economy as knowledge, skills, services, and small business based7. Society in Britain had also seen a transformation in the role of women and the erosion of the traditional class system.

More women than ever before were entering the job market, and in turn, political institutions needed to adapt to these societal changes. Blair and New Labour were there to offer the third way as a new model of government that could meet this need8. By 1998, Labour had issued its major New Deal programs aimed at reducing unemployment and part of his overall ‘’Welfare to Work’’ strategy. Using the funds from a 5 billion pound windfall tax on privatized utility companies, its first aim was at the youth unemployed (18-24 years old). The New Deal for Young People was the main target of New Deal funding and emphasis.The New Deal program also held a stipulation that it had the ability to withdraw benefits from those who refused employment9. Essentially, New Labour had paralleled the Clinton Democrat strategy of enacting policies to make work pay while its initiatives aimed to improve human capital of welfare recipients10. Also like Clinton Democrats’ acquiescence to Reaganomics, was Blair’s willingness to ‘’accommodate the legacy of Thactherism’’11.

Critics on the left of the Labour party objected that the emphasis put on equality of opportunity would have little to no effect on the distribution of resources within classes. As Stephen Driver and Luke Martell criticize in the New Labour Reader, ‘’The distribution of wealth and income remains a major determinant of the opportunities an individual has in life12.’’ The New Deal programs would eventually expand to targeting long term unemployed adults over the age of twenty-five and fifty, lone parents, the disabled, and even unemployed musicians13. In the first year of the New Deal for Young People’s implementation, youth unemployment fell by 40% and by 2000 unemployment had reached its lowest levels since 197414. While the economy under Blair and New Labour seemed to be thriving, critiques from the left provide other factors that were obscured amidst the prosperity at the time.

Critics on the left of the Labour party objected that the emphasis put on equality of opportunity would have little to no effect on the distribution of resources within classes. As Stephen Driver and Luke Martell criticize in the New Labour Reader, ‘’The distribution of wealth and income remains a major determinant of the opportunities an individual has in life12.’’ The New Deal programs would eventually expand to targeting long term unemployed adults over the age of twenty-five and fifty, lone parents, the disabled, and even unemployed musicians13. In the first year of the New Deal for Young People’s implementation, youth unemployment fell by 40% and by 2000 unemployment had reached its lowest levels since 197414. While the economy under Blair and New Labour seemed to be thriving, critiques from the left provide other factors that were obscured amidst the prosperity at the time.

Blair continued the Tory policy of fiscal discipline and squeezes on spending. Blair further shrunk public investment from 1.6% of GDP during the Major government to .6% from 1997-2001- the lowest amount for any post war government15. Under Major, public enterprises were encouraged to contract services to private companies, paving the way for a closer relationship between business and government.

Under Blair, this trend was expanded to the administration of welfare, dentistry, and prisons. As of 2007, subcontracting reached 20% of public expenditure (68 billion pounds)16. Criticism of continued Tory trends was noted by many on the left. Assistant Editor of the New Left Review, Tony Wood, on the effective privatization of the Bank of England and other similar policies stated: ‘’The philosophy underpinning this is a managerial one: Here again Labour has accelerated a development that began under the Tories, setting a welter of targets- Blair proudly claimed 500 at the 1999 party conference-covering everything from hospital waiting lists to museum visits17.’’

Further argued by Stuart Hall in his article ‘’The Great Moving Nowhere Show’’: ‘’New Labour’s economic repertoire remains essentially a neo-liberal one: the deregulation of markets, wholesale refashioning of the public sector by new managerialism, the conned privatization of public assets, and low taxes among others18.’’ Other key reforms, changes, and reflections of New Labour values echoed by Hall and Wood were: a new structure of financial regulations, new fiscal rules and a five year reduction deficit plan, major corporate tax reform under the ACT, and the reforming of the finance of higher education among others. New Labour, behind its reforms and attempts to juggle conflicting ideologies, firmly did not trust the Keynesian political economy. New Labour strayed away from putting any emphasis on state involvement when it came to welfare reform, public investment, and/or regulating the corporate business structure19.

Nonetheless, from 1997-2001 the economy boomed. By 2001, the share of debt was at 39% of GDP one of the lowest in the EU and Blair planned to cut it further to 33%. In addition, the budget of 2002 proposed significant extra funds to health and education using ‘’stealth taxes.’’ Although, as many critics on the left claim, this did not make up for Blair’s incessant neo-liberal/deregulating policies that perpetuated the greed that showed its bubble/bust colors in recent years. Blair did do more than the Conservative party when it came down to welfare, the unemployed, and social policy, but New Labour became a lesser of two evils for many on the left who saw the party betray them. As this essay will point out, economics had a very small part in that mentality compared to Blair’s commitment to the Iraq War and New Labour’s radically altered foreign policy.

New Labour’s approach to foreign policy coming into Blair’s premiership concentrated more on international cooperation, with states working together to uphold peace. Early on, Blair soared in foreign policy. He achieved historic success in Northern Ireland with the Good Friday Agreement, forced Milosevic’s capitulation in the Kosovo War, and the success of the extremely risky rescue mission in Sierra Leone contributed to Blair’s widespread popularity and increased trust the British people had with their leader.

Throughout Blair’s premiership leading up to the Iraq War, he had built an extremely close relationship with President Clinton and subsequently became seduced by the bond with Britain and the U.S. The controversies over the Iraq War would ultimately drive Blair’s government to strictly alter its foreign policy. The Iraq War became more or less a war of values for Blair, rather than eminent danger (especially as the war lingered on).

The specific reasons and justifications for Blair going into the Iraq War weave away from the focus of New Labour values and is more of a visceral reaction by Blair. It is clear that Blair was fully committed to President Bush under any circumstance even with the scrutiny and vilification that was severely tarnishing his legacy. Not only that, but as the Chilcot Inquiry points to, Blair indeed misrepresented the WMD program in Iraq when he said in 2003 that “intelligence on Iraq’s WMD program was extensive, detailed, and authoritative20.”

In the inquiry, it was clearly found that MI6 understood Saddam had ‘’no nuclear weapons or significant WMD’’ in 2002. So, one could in fact argue that this contributed to the notion of New Labour being little more than a set of ideas waiting for where the wind would blow next. In terms of foreign policy, Blair didn’t necessarily deter from New Labour values because he was discontented with them, it was simply because it didn’t fit his own agenda at the time. He had made a pact with Bush, and while perhaps there may have been a moral impetus for Blair, the New Labour ideological basis for foreign policy before the war seemed moot. One can elaborate at length on the consistent blunders, lies, and tribulations that Blair left the nation with during the Iraq War. Be that as it may, the war caused a major rift within the party, aligned Blair even further with a centre right image to many on the left, and would subsequently become the most damaging event for Blair and New Labour.

In terms of social policy, New Labour glided with modern calls for robust equal human rights. The rights of the LGBT community were wholly embraced by Blair and New Labour. During Blair’s first term the age of consent for homosexual intercourse was equalized at 16, the ban on gays in the armed forces was lifted, 2005 Civil Partnership Act allowed gay couples to form legally recognized partnerships, adoption for gays was legalized, and discrimination in the workplace of sexual orientation was made illegal21. Blair’s image, more so than the overall New Labour brand, was viewed as a youthful Prime Minister flowing with the modern era. This was not only a theme in social policy, but dating back to his work in revitalizing the Labour party before he became Prime Minister. The ability to adequately represent the society in which he governed was essential for Blair, and subsequently New Labour. New Labour’s main intention was to be able to stay in tune with the current clamor, and in that sense New Labour became a permanent fixture.

New Labour reflected a dynamic shift not limited to British politics, but globally. In a world dominated by globalization and capitalism, it would have been a tumultuous challenge to win an election based on Keynesian economics with the progression the world had seen at that time. It does not mean, however, that Tony Blair and New Labour were given care blanche to shift the party as much to the right as it did. It was not the values that had changed so much, but the way in which Blair operated. The obsession over appearances, media blitzes, and a revered admiration for the elite by Blair. His close relationship with Rupert Murdoch, the scandals over political favors, and political savagery as in the case of Mayor Livingstone. All of these sketchy ties one would expect from a party that represents the higher echelon of society, not a party dedicated to the welfare of all. New Labour also represented the new smug detachment of the Labour party with the common man. To say New Labour was little more than a set of disconnected ideas obscures its revitalization of left politics in Britain. It certainly was a project dependent on sacrificing certain core principals for electoral success, and by this measure alone it succeeded.

References for New British Labour Party:

1 Judi Atkins, Justifying New Labour Policy, Macmillan Press: London, UK, (2011), Pg. 82.

2 Judi Atkins, Justifying New Labour Policy, Macmillan Press: London, UK, (2011), Pg. 93.

3 Judi Atkins, Justifying New Labour Policy, Macmillan Press: London, UK, (2011), Pg. 94-5.

4 Judi Atkins, Justifying New Labour Policy, Macmillan Press: London, UK, (2011), Pg. 95.

5 Richard Hefferman, ‘’New Labour and Thatcherism’’, The New Labour Reader, Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, (2003), Pg. 50.

6 Tony Blair, ‘’The Third Way: New Politics for the New Century’’, The New Labour Reader, Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, (2003), Pg. 33.

7 Judi Atkins, Justifying New Labour Policy, Macmillan Press: London, UK, (2011), Pg. 102.

8Judi Atkins, Justifying New Labour Policy, Macmillan Press: London, UK, (2011), Pg. 128.

9 Colin Hay, ‘’The Political Economy of New Labour’’, The New Labour Reader, Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, (2003), Pg. 59-60

10Judi Atkins, Justifying New Labour Policy, Macmillan Press: London, UK, (2011), Pg. 105.

11Colin Hay, ‘’The Political Economy of New Labour’’, The New Labour Reader, Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, (2003), Pg. 63.

12 Stuart Hall, ‘’The Great Moving Nowhere Show’’, The New Labour Reader, Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, (2003), Pg. 85.

13 Colin Hay, ‘’The Political Economy of New Labour’’, The New Labour Reader, Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, (2003), Pg. 62.

14 Colin Hay, ‘’The Political Economy of New Labour’’, The New Labour Reader, Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, (2003), Pg. 62-3.

15 Colin Hay, ‘’The Political Economy of New Labour’’, The New Labour Reader, Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, (2003), Pg. 64.

16 Anthony Barnett, ‘’Corporate Populism and Partyless Democracy’’, The New Labour Reader, Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, (2003), Pg. 89.

17 Tony Wood, ‘’Good Riddance to New Labour’’, New Left Review, March-April 2010.

18 Stuart Hall, ‘’The Great Moving Nowhere Show’’, The New Labour Reader, Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, (2003), Pg. 85.

19 Will Hutton, ‘’New Keynesianism and New Labour’’, The New Labour Reader, Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, (2003), Pg. 119

20 Jason Groves, ‘’How Blair Still Went to War Despite MI6’s Damming Evidence’’, The Daily Mail, April 7, 2013.

21 Anthony Seldon, Blair’s Britain 1997-2007, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, (2007), Pg. 172.

Leave a Reply