This year’s Academy Awards competition, which is also called the Oscars, provides an opportunity to better understand why governmental elections often produce such wild results.

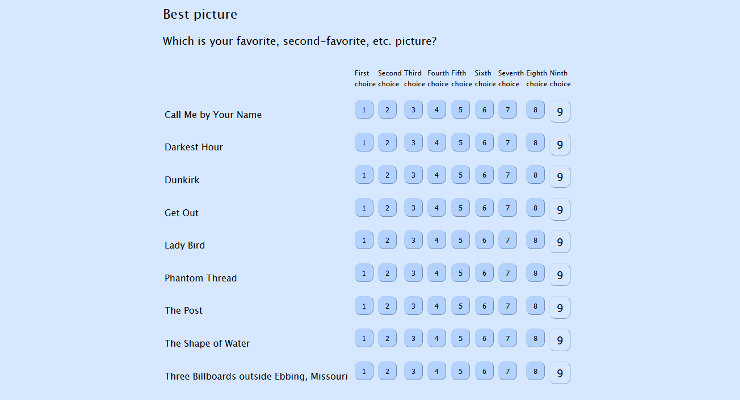

A new Oscars poll at NewsHereNow.com/polls demonstrates how voting should be done.

Why another Oscars poll? The usual approach for nearly every online poll is to ask each voter which choice is their favorite, and then count these preferences to yield one count for each choice. The choice with the biggest count is — incorrectly — assumed to be the most popular.

This simplistic kind of vote counting works fine when there are just two choices. And sometimes it works when there are three, or possibly four, choices. But each added choice increases the likelihood that the winner will not be the most popular choice.

This year the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) has nominated nine (9) movies in the Best Picture category. This is too many choices for simplistic vote counting because the choice with the most single-mark votes is not necessarily the most popular.

Only if one of the choices receives more than half the votes can we be sure that the choice is really the most popular. Yet that becomes less likely as the number of choices increases.

Interestingly the choice with the fewest single-mark votes is not necessarily the least popular. Alas, the official AMPAS voting process makes this mistaken assumption.

When there are more than two choices, pairwise counting provides a much fairer way to handle voting. This approach requires asking each voter to fully rank all the choices, using what’s called a 1-2-3 ballot. Each voter indicates his or her first choice, then a second choice, then a third choice, and so on.

If a voter isn’t sure how to fully rank all the choices, then more than one choice can be ranked at the same preference level. And if a voter really doesn’t want to think beyond their first choice, it’s OK to rank a single choice as most popular and leave all the remaining choices ranked as equally least-popular, which is equivalent to how we currently have to mark election ballots.

With this extra ranking information it becomes possible to look at each pair of choices, one pair at a time. For each pair, we can count how many voters prefer one of the two choices over the other, and count how many voters have the opposite preference.

Usually we can look at all these pairwise counts and quickly see which one of the choices (which can be a political candidate or a movie or an actor or an actress) is clearly the most popular choice.

The NewsHereNow Oscars poll allows you, or anyone who is familiar with the Oscar-nominated movies, to rank the movies using a 1-2-3 ballot. And then computer software automatically does the pairwise counting and correctly identifies which movie is really most popular among the voters. (If you should want the calculation details, you can view the software’s source code at GitHub.com in the CPSolver account.)

The software also identifies which movie is second-most popular, third-most popular, and so on, down to least popular. For all nine movies! In contrast, simplistic single-mark ballots, on which each voter can only mark a single choice, does not provide enough information to calculate this full popularity ranking. (Remember that the choice with the fewest single-mark votes is not necessarily least popular.)

There is another advantage to pairwise counting. It allows the NewsHereNow Oscars poll to combine the actors category with the actresses category, so we can learn how any pair of actor and actress compares in popularity. This poll also combines both original screenplays and adapted screenplays into a single question so that we can find out which screenplay is really best overall. With this grouping the poll has only three questions:

- movies

- actors/actresses

- screenplays

Although this Oscars poll has just three questions, we can still identify winners in these five official categories:

- best picture

- best actor

- best actress

- best original screenplay

- best adapted screenplay

That’s because 1-2-3 ballots and pairwise counting makes it possible to calculate the full popularity ranking of all the choices in each question, from most popular, second-most popular, and so on down to least popular.

How does this relate to political elections? The 2016 Republican U.S. presidential primary election demonstrated the unfairness of using single-mark ballots and simplistic counting. In that election there were seventeen (17) candidates! Officially the winner only had to get more single-mark votes than any one of the other candidates.

To appreciate why that’s unfair, imagine what might have happened if we knew the pairwise count between Donald Trump and Ted Cruz, and the pairwise count between Donald Trump and Marco Rubio, and the pairwise count between Donald Trump and John Kasich, and the pairwise count between Donald Trump and Jeb Bush. There is a reasonable chance that Trump might have lost all four of these pairwise contests, and instead a different candidate might have won all his pairwise contests.

To better appreciate this possibility, keep in mind that Trump received just 45 percent of the votes from Republican voters, which means 55 percent of Republican voters voted for someone else. And Trump would have received even fewer single-mark votes if the other candidates had not dropped out of the race before voting ended.

In other words, because there were so many candidates, the single-mark ballots in that primary election did not give us enough information to correctly identify which candidate really was most popular among Republican voters.

This insight reveals an extremely important point. It’s in the primary elections where the biggest unfairnesses occur! Why? Because that’s when there can be (and should be) more than two main candidates. And that’s where money has the most significant influence in U.S. elections. Later, in the general election, we only get to choose between the money-backed Republican candidate and the money-backed Democratic candidate.

So, if you are a U.S. citizen who usually doesn’t bother to vote in primary elections, wake up! That’s where we, the voters, actually have lots of influence. Especially in the 2018 primary elections, when lots of reform-minded candidates will be listed on ballots. It’s an opportunity to make a difference in the conflict between the political up — which is where most of us voters are — and the political down — which is where the biggest campaign contributions come from. This up-versus-down conflict is much more important than the smaller distraction between the “political left” and the “political right.” (To learn more about this concept, see the wild election results article.)

Now you’re ready to understand the hidden strategy that the biggest campaign contributors use to control who wins each primary election. The strategy doesn’t have a name, but it should, so let’s call it the money-backed-vote-splitting tactic.

How does this tactic work? In backroom meetings, people who represent the biggest campaign contributors decide which candidate in each primary race will be their money-backed candidate. If a popular reform-minded candidate enters the primary race, then some money is indirectly and quietly given to a second reform-minded candidate who unwittingly becomes a “spoiler” candidate. The spoiler candidate “splits votes” away from the first reform-minded candidate. And some extra money is spent on advertising to further support the money-backed candidate. The result is that the money-backed candidate usually wins because he (or rarely she) gets more single-mark votes than either one (but not both) of the reform-minded candidates.

In other words, when needed, money is used to increase the number of candidates, and the tactic becomes the well-known divide and conquer strategy. This very legal tactic works even when a majority of that party’s voters oppose the money-backed candidate. As an example, this tactic contributed to why money-backed John Kerry won the 2004 Democratic presidential primary election against reform-minded candidates John Edwards and Howard Dean, with Dean initially getting some money to split votes away from then-popular candidate Edwards.

Now you can better appreciate why we have primary elections. Back before U.S. primary elections existed, there were just “elections,” the ones we now call general elections. Whichever political party had two candidates almost always lost to the political party that had just one candidate. So primary elections were established to eliminate vote splitting.

To the delight of the wealthy people in the political down category, primary elections hide the unfair use of single-mark ballots. The unfairness is hidden because the winner of a primary election is always from the correct political party. Consider that most voters and most news reporters only focus on which political party wins a race. And consider that most research polls don’t ask respondents to rank all the choices, leaving us without enough information to do even unofficial pairwise counting.

Alas, U.S. primary elections are flawed. Yet they are better than what happens in most other nations, where only political-party insiders participate in choosing their party’s nominee.

Fortunately when more U.S. citizens understand the money-backed-vote-splitting tactic, the tactic can be defeated. So, please help your friends and relatives — on both the “political left” and the “political right” — understand this tactic.

The NewsHereNow Oscars poll allows us to put aside our strong political opinions, and instead focus on entertainment. So, if you’re familiar with the main Oscar-nominated movies, you can have fun ranking the nine movies, ranking the 10 actors and actresses, and ranking the 10 screenplays. While marking the ballot you will be learning how voting really should be done.

Here is the link to vote now:

It’s free, there are no ads, and no signup is needed.

Have fun!

Leave a Reply