An article published recently in Germany’s Die Welt newspaper (by Annette Prosinger) forebodes the possible downfall of democracy in Spain owing to the debilitating financial crisis that has been weighing this country down since 2008. The Spanish government, whose credibility has been tainted by allegations of corruption and ineptitude, has thus far been unable to provide solutions to problems such as crippling unemployment, tax hikes and a housing crisis that has forced many families to lose their homes. The people’s sense of hopelessness, argues Prosinger, is threatening “the very basis of democracy: the political culture”.

Prosinger’s opinion is more than well-founded; if in 2009, a CIS (Center of Sociological Investigation) poll indicated that 85% of Spaniards believed in democracy, a more recent study reveals that only 61% now believe democracy to be the best system. Some 20% of the population, meanwhile, believe that democracy has serious shortcomings; 57% believe that democracy would work better by replacing political parties with social platforms chosen by the people. Meanwhile, some 72% of Spaniards have lost their faith in the EU, believing the euro to have caused greater harm than good.

Prosinger’s opinion is more than well-founded; if in 2009, a CIS (Center of Sociological Investigation) poll indicated that 85% of Spaniards believed in democracy, a more recent study reveals that only 61% now believe democracy to be the best system. Some 20% of the population, meanwhile, believe that democracy has serious shortcomings; 57% believe that democracy would work better by replacing political parties with social platforms chosen by the people. Meanwhile, some 72% of Spaniards have lost their faith in the EU, believing the euro to have caused greater harm than good.

The ruling bipartisan system is also at threat, with 87% of the people preferring a system comprising more parties which are smaller in size, than one which favors the existence of large parties such as the ruling PP (and the current Spanish ‘opposition’, the PSOE). If, in 2011, these two parties attracted 52% of the public vote according to census, that number has dropped to 33%, according to CIS. As leading Spanish journalist, Belén Barreiro notes, “the consensus regarding the type of country we desire, in a political and economic sense, has been destroyed… behind the fall from grace of democracy lies the economic crisis, the crisis in institutions and, in particular, the destruction of social cohesion.”

Consensus might be achieved once the crisis is over, says Barreiro, but the people’s loss of faith is irreversible and is likely to lead to important changes, including the support of populist candidates, a search for economic alternatives to capitalism, the downfall of the bipartisan system, and possibly, a demand that Spain exit the European Union, despite foreseeable short-term losses.

Harsh Facts and Figures of the Spanish Recession

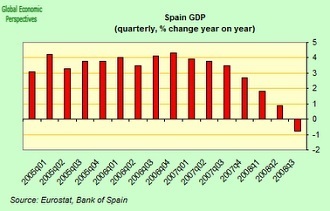

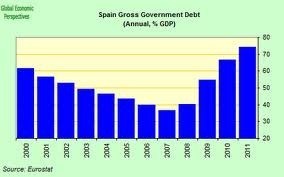

On April 26, Spain’s President, Mariano Rajoy, conceded the failure of the PP’s First Reform Plan and announced its Second Reform Plan. The First Reform Plan’s primary aim was to reduce the public deficit, but the figures indicate that its goal has been sorely missed. In 2011, Spain’s public deficit amounted to 9.6% of the GDP; by the end of 2013 it is projected to reach 10.6%.

The First Reform Plan’s second aim was to foment growth; once again, the trend indicates the opposite: a reduction of 1.6% of the GDP in 2013, and a projected growth of only 0.9% by 2015. The Spanish economy required a growth of around 2% of the GDP to generate employment, yet since 2011, some 1.6 million jobs have been lost. It is estimated that by 2015, unemployment will hit a high of 28.8% and the double recession’s effects on unemployment are projected to last way beyond 2015. By 2015, experts are predicting the downfall of the bipartisan system; by then, unemployment is set to reach a record figure of 30%.

The First Reform Plan’s second aim was to foment growth; once again, the trend indicates the opposite: a reduction of 1.6% of the GDP in 2013, and a projected growth of only 0.9% by 2015. The Spanish economy required a growth of around 2% of the GDP to generate employment, yet since 2011, some 1.6 million jobs have been lost. It is estimated that by 2015, unemployment will hit a high of 28.8% and the double recession’s effects on unemployment are projected to last way beyond 2015. By 2015, experts are predicting the downfall of the bipartisan system; by then, unemployment is set to reach a record figure of 30%.

A Bleak Future for the Youth

Fresh statistics indicate that youth unemployment has hit the worrisome figure of 50%, despite the fact that a significant percentage of the youth have been educated or trained to carry out specific jobs. Renowned blogger Ignacio Escolar, former Editor of the newspaper, Publico, exclaimed, “This generation is, at once, the least hopeful and the best educated that Spain has ever seen.”

One of the main causes of the recession is the ‘housing bubble’ (which started in the late 1980s and continued until the early 2000s), often criticised by Germany’s Angela Merkel. Germany is currently forcing Spain to adopt severe ‘austerity measures’ yet it fails to acknowledge the important role it has played in the creation of the housing bubble, through the support afforded by German banks to speculative banking and real estate ventures in Spain during the real estate boom. Merkel’s austerity measures aim to increase Spain’s competitivity but they are, in fact, destroying an already seriously under-funded Spanish welfare state.

The recession is seeing significant rises in suicides and drug abuse, with many families unable to meet their basic needs; yet cuts to the health care system mean that the state is unable to meet the new demand posed by those suffering from depression or addiction. It is interesting to contrast the conditions enjoyed by addicts in the US, in states such as New Jersey or California where support is provided at deeper levels to addicts and their families; with hotlines and helplines, dedicated programmes for the disabled, a choice of in-house programmes and ensured access for all consumers. If the US leads the world in prescription drug abuse, Spain comes second, yet rehabilitation programmes fail to come up to scratch, with most treatments offered on an outpatient-only basis. Drugs are also touching families from the other end of the spectrum, with drug trafficking rising in poverty-stricken areas such as Cádiz, in the South of Spain.

What Does the Future Hold?

Many journalists have already begun asking themselves why the Spanish people have not revolted, citing the following causes for the maintenance of the status quo: the people’s rejection of the political culture and the ensuing sense of alienation and impotence; the stable per capita income in Spain; and the people’s fear of losing the little they do have. What seems clear is that although some stability remains, Spain is on the cusp of a major change in its political structure.

Leave a Reply