As academics, we think too much. As adjunct faculty, we are paralyzed and thus afraid to think, to act. As Americans, we have forgotten what civil disobedience really means.

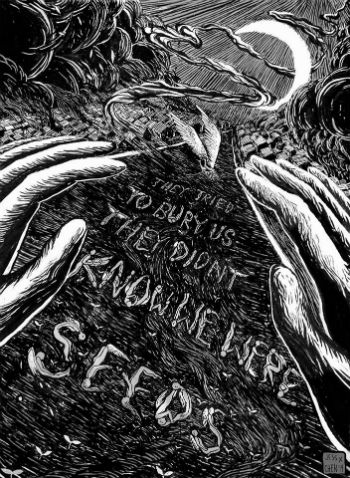

We can learn a lot from the normalistas, the students in Ayotzinapa, who are the seeds of Ayotzinapa.

Yet when I was watching the goings-on of what has been occurring in Ayotzinapa – the horrors of what is relentless today in Mexico, the beautiful country that first gave me refuge when I was a little girl – it does not cease to amaze me. The energy, raw and visceral, that I see coming from everyday people – students, community, activists – inspires me to think that grassroots activism and civil disobedience can happen and will affect change.

I have been watching the events take place as if I were living some sort of phantasmagoric nightmare. Could this really be occurring? I do not know it; I do not understand it. I remember as a little refugee girl from Cuba leaving Mexico because my father whispered that the government “era corrupto.”

So we came here – to the United States – where I grew up sheltered and coddled.

I wonder how much things have changed since we first arrived, seeing the recurring violence enacted on so many black and brown…

Daily, I read what is happening in our own communities of color. There is a divide of inequality here, just as the divide we so disdain everywhere else, in every other country, in Mexico.

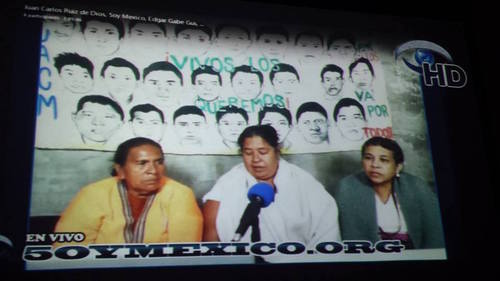

As I watched the live-feed of Ya Nos Cansamos Solidarity Network – the first (hopefully!) one-of-a-kind dialogue between several universities and community organizations in California, Mexico City, Chiapas, Missouri, Nevada, Rhode Island, New York, New Mexico, Arizona, Illinois, Seattle, and Texas with Ayotzinapa and the indigenous communities of Guerrero, Mexico – it became clear that this was the perfect anarchists’ creation, and a sure sign of hope for the future.

Maybe with this initial video conversation from the trenches, real change can begin to occur.

We can only hope.

Though the connections between California activists and friends with the indigenous communities had long been established, and conversations had been ongoing for months, the speed at which technology opened up the means for dialogue was mind boggling. Within six days our bilateral conversation took flight, and as my colleague Vanessa Vaile from Precarious Faculty already reported, the u-stream was a huge success, notwithstanding a few preliminary hiccups. She counted over 1500 participants just from the u-stream views alone, and that did not include views from multiple sites across the US or Mexico, as well as other countries.

So if we count the followers on Twitter and Facebook, of which there were plenty, how many more are we speaking about? Capsulizing the two hour session a few days later with a friend – Antonio Arias, one of the organizers of this historic event – he said he was sure it had been thousands.

For a first time, I think this anarchists’ dialogue was ¡un éxito!

So I went to the rally Dallas for Ayotzinapa held the next day, part of the #USTired2 nationwide day of protest, to stand with my colleagues in Dallas in support of Ayotzinapa, and to report what had happened at the video conference. The crowd was smaller this time than the week before. This was our second demonstration at this site, the Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge.

We were holding this protest to defy United States support of the Mexican government. With our patronage — we were saying — were we not all complicit? It was still a good crowd for such a red state. We even had what I thought might be a police helicopter pay us a visit for about 10 to 15 minutes. It was trying to deafen us, pressuring us to leave voluntarily with its insistent roar.

I went to stand quietly by my colleagues, but one of the organizers asked me to speak, to tell the crowd what had happened the night before at the video conference.

I am not a speaker; I am a writer. I get tongue-tied and become all hands and feet. I muttered quickly how many people had listened, approximately; what a historic event it was; how we wanted to translate the Spanish sections for all to understand, but that I could give them the Spanish version on YouTube once it was uploaded. Moreover, there were some photos of the event so far; at least I could give them that now.

I finished.

I am not much of a public speaker.

Instead, I kept hearing Omar García’s monotone voice reverberating against my ears, his smooth soft sound like a muted lament, his quiet gaze pleading, yet I did not wonder why: he must mask his pain, or fear losing everything in that constant memory of dread.

I kept going over the account of what these two normalistas had said, these two boys who had survived those nights of horror in Ayotzinapa as the Iguala municipal police and other armed men surrounded and ambushed the three buses carrying the students, with collusion from the Mexican Army.

All the normalistas wanted was to raise money for their school and their struggle against inequality.

I could not think of anything else except for these boys and their grieving mothers.

I brooded about the mother of Ferguson’s Michael Brown here in the United States too – that mother who had wanted to be with us during our video conference to make crossover ties – and of another Ferguson mom who spoke of the pain we all felt in the United States at the injustice rendered, especially in Ferguson.

The grief of the brown and black.

So I lost sight of the helicopter hovering above. I stopped hearing word for word what was going on. Instead I pictured the dozens of students trying to escape every which way, barreling crazed through the streets, dizzy with fear, as they heard shots and shouts and angry voices, as they realized their classmates were being loaded up onto police vehicles. The rain kept pounding down onto the pavement, and a few of them hid between the buses, one dead between them. Another had been hurt, and they tried to take him to a hospital, but no one would help.

I remember Omar García then glanced up, looking eerily through the camera. “They are after not only education,” he warned. “They will destroy all sectors of society.”

Omar seemed to look across the miles, a very old wizened gaze in such a young body, and he asked: “Do you understand why we leave our country, why many of us flee? We have no home here. We are forced out by our own government.”

He continued: “Even though we are young and poor, we will not bow down, and the government cannot stand our defiance.

They want us out.

In Chilapa 11 were beheaded. In Puebla, others have disappeared. On November 20th, el Día de la revolución, 11 more protesters were arrested in the capital. Mexico, and the world at large, made such a scandal that the government had no choice but to set the protesters free, citing there was not enough evidence.

As if they had ever needed evidence before.”

This young man exclaimed in his monotone voice, a voice filled with a tremor there was no mistaking. “We have to make changes,” he persisted; “we need to reorganize from the bottom up. We cannot continue to endure these constant massacres, these habitual murders.

Since 1935 we have been in this struggle,” Omar wavered; “we have been at this, fighting day in and day out for many long years” (no wonder my father had repeated this so long ago about Mexico’s corruption). “They are the cabrones,” he cursed; “the government is always stealing, murdering.”

Then Omar García almost wailed his plea: “This should not have happened to awaken my people! How many people are dead? Where are my friends?”

The young man went on: “Right now they cannot touch us,” he continued, “but in a while, they will. We are all afraid. BUT we have unified the people of Mexico. Hopefully we have reached across the nations. It is horrible that this should have happened. But we are saying enough. We are saying we are united in asking for justice.

Why?”

The boy looked out across the space and motioned:

“Because we want our own people back.

They will not forget us.

They will not forget that 43 poor families have hijacked the Mexican government.”

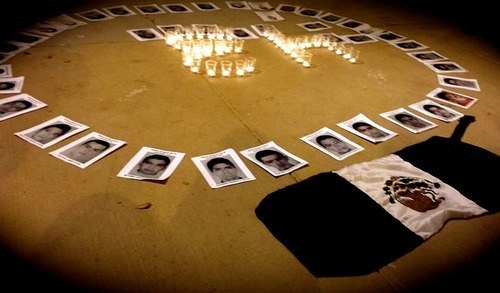

As the voices at the bridge in Dallas called me back from my reverie, I joined in the chant. We called out each name of the normalistas of Ayotzinapa, one after the next after the next, until we read all 43, exclaiming ¡Presente!

Each of us carried a student’s photograph.

We would walk over with the reminder in full color of that disappeared student and lay it down softly, in a circle surrounding 43 candles, lit in the shape of 43…

Presente…

Leave a Reply