by Michael Ossipoff

In previous articles published on Democracy Chronicles, I have discussed Approval strategy, Score strategy, the Chicken Dilemma, Strategic Fractional Ratings (for the Chicken Dilemma), considerations favoring some methods over the others, and more. In this article I will summarize those subjects, putting them together in a numbered and lettered outline form in order to provide more clarity. I think that with this numbered and lettered outline-format, this article will be much clearer.

Though I might briefly mention things that I’ve already discussed, I won’t repeat long explanations of those things but will, instead, refer readers to the previous articles in which I discussed those subjects. So, rather than writing in detail about strategy topics that I have already discussed, I will outline them in order to show the relationship between the different topics.

The main focus of this article will be on Approval and Score—the feasible proposals—clarifying their strategy and the choice between them. For official public elections, Approval is the feasible proposal or perhaps Approval and Score. In my first article here (“Some Problems with Plurality”), I explained that Approval is the natural, obvious, minimal, but powerful improvement on the “Plurality”, “Vote-For-1”, method that is currently in use. Rank methods bring two feasibility problems:

- Computation-intensive count, probably needing machine balloting and computerized counting, with consequent count-fraud problem

- The vast variety of ways of counting rank ballots, making it difficult or impossible for any particular rank-count to gain agreement, acceptance, and adoption.

Approval and Score are feasible because of their easier, more secure, count, and the obviousness that results from their simplicity.

Table of Contents:

1. Brief Definitions of Approval and Score

2. Score Count

3. Approval and Score Strategy

a) With No Chicken Dilemma

b) What It Takes to Have a Chicken Dilemma

c) Dealing with the Chicken Dilemma

1. Why It Isn’t a Great Problem

2) Strategic Fractional Ratings (SFR)

d) Only Two Reasons to Give Fractional Ratings

e) How to Give Fractional Rating in Approval or 0-10 Score

4. Score Advantages

5. Approval Advantages

1. Brief Definitions of Approval and Score

Approval and Score are point systems. Point systems are voting systems in which voters can give to any candidate however many points they want to. The candidate with the most points wins. Approval is the 0–1 point system. The voter can “approve” (give 1 point instead of 0 points) to as many candidates as he or she wants to.

Score consists of the point systems with more than two rating-levels such as 0–10 Score or 0–100 Score. For example, in 0–10. Score, you can give to any candidate, any rating from 0 points to 10 points. Score was called “Range” for quite a while. Score is the name most commonly used now, however “Range” will often be seen—mostly in older articles and postings. Score was also previously referred to as “Cardinal Ratings.”

2. Score Count

The obvious way to count Score, when processing each ballot would be to read that ballot’s rating of the ballot’s first candidate, and then to add that rating to that candidate’s running total. But count-labor equals count-fraud opportunity. Is there an easier way to do the big—hopefully open and public—hand-count for Score?

Well, suppose that the method is 0–10 Score. A better count method would be what could be called an “instance-tally”: For each candidate, keep tallies of the number of ballots giving 0 points, the number of ballots giving 1 point, the number of ballots giving 2 points, and so on. In other words, for each candidate, for each rating level available, keep tallies of the number of ballots giving him/her that rating. That means that, in 0–10 Score, you’re keeping 11 tallies for each candidate.

When processing each ballot, if it gives P points to candidate C, then increase C’s P-point tally. Then look at the ballot’s rating of the next candidate, and do the same. In that way, the counters aren’t adding the ratings to running totals. They’re just incrementing some tallies. If there are NC candidates, then, in 0–10 Score, there will be NC multiplied by eleven tallies. That’s a manageable number of tallies.

But Approval is much better in that regard, because there is only one tally for each candidate (no need tally the number who didn’t approve him—for that matter, Score could similarly get by with 10 tallies for each candidate, instead of 11). Of course Score 0–100 would require a lot more tallies. For that reason, 0–10 Score looks a lot more feasible than 0–100 Score. Anyway, after the public Score count, each candidate’s 10 or 11 tallies could easily be published and posted. Then, from those, anyone could determine the winner. Take a look at this example of Score Voting:

3. Approval and Score Strategy

a) With No Chicken Dilemma

This information can be found in the article entitled “Some Problems With Plurality”, toward the end, under the heading “Approval Strategy.” Basically, if you are certain that there are some candidates that you like, or trust, but not the rest, then approve them. If there are some candidates who are outright unacceptable, and they could win, then approval (only) all of the acceptable candidates.

If there aren’t unacceptable candidates who could win, and you want to vote strategically, approve the better-than-expectation candidates. For example, you could ask yourself, for each candidate, “Would I rather appoint him or her to office than hold the election?” If so, then approve him or her, because she’s better than what you expect from the election. But don’t be pessimistic about what you expect.

I claim that voting is a matter of optimism. First, your judgment about your expectation should be optimistic. Then you should approve only candidates who are better than what you expect from the election. Of course, by helping those better-than-expectation candidates, you’ll pull your statistical expectation upward. Better outcomes come with optimistic voting. The results will reflect your optimism.

If the election is by Score, then give maximum points to the candidates whom you’d approve if it were an Approval election; give minimum points to the others. Of course, in 0–10 Score, the minimum is 0, and the maximum is 10.

b) What It Takes to Make a Chicken Dilemma (I suggest four requirements for a Chicken Dilemma)

b1) The candidate in question should be someone who qualifies for approval by the considerations discussed above in a)

b2) His/her supporters like your candidate better than some candidate whom both factions like less than each other’s.

b3) But they’re likely to strategically 0-rate your candidate, taking advantage of your help for theirs.

b4) You care. (Maybe you just want to defeat Worst, by max-rating Compromise, even if his/her supporters defect. Or maybe it’s more important to show them that defection won’t work, to give Favorite a fair chance.

c) Dealing With the Chicken Dilemma

c1) Why it isn’t a great problem

There are a number of reasons why the Chicken Dilemma won’t really be a problem in Approval or Score: The other faction will know that your faction won’t help them next time if they defect. It’s difficult or impossible to keep defection secret, due to conversations, discussions, media discussion, etc. Parties or candidates can make non-defection promise agreements. Tit-For-Tat strategy is available (Over time, do as the other faction did last time—co-operate or defect, as they did).

c2) Strategic Fractional Ratings (SFR)

I’m speaking of a strategy for your whole faction, not just for one voter. If there is a Chicken Dilemma, regarding a certain candidate (“Compromise”), you can give to him/her some little “fraction-of-max” boost, enough to have a good chance of closing the gap between Compromise and Worst if Compromise is out-scoring Favorite‑—without being enough to be unduly help Compromise beat Favorite if Compromise would otherwise score lower than Favorite.

Obviously the above is a matter of pure guesswork—intuitive and subjective. The paragraph before this one tells the purpose of SFR. It doesn’t tell you how to judge the right fractional rating. That’s guesswork. But Compromise’s faction doesn’t have better information than you do. And so your guess carries some weight. The defection deterrence of SFR is genuine.

In an earlier article I discussed some types of faction-size assumptions and estimates that you could make, and suggested some formulas that you could use for SFR, based on those assumptions and estimates. However being based on estimates (guesses, really) that formula approach is really no more objective than the pure guesswork that I described in the paragraphs before this one. Use the formula approach only if you like it better. I prefer the direct pure guesswork approach described in previous paragraphs.

d) There Are Only Two Reasons to Give a Fractional Rating

d1) If there is a Chicken Dilemma

d2) If you don’t feel sure about whether a candidate is someone, whom you should approve, based on the considerations that I discussed under “If there isn’t a Chicken Dilemma”.

For instance, say it feels like a 50/50 (50% percent probability) chance that candidate X should be approved. Then give to him/her a fractional rating of 50 percent of max. And if it feels like a 75 percent chance that he or she should be approved, then give him/her .75 max as nearly as the Score version will allow. In 0–10 Score, you can give a candidate .5 maximum by giving him/her 5 points. You can give him/her .75 maximum by giving him/her 7 or 8 points (flip a coin). As for Approval, I get to that next:

e) How to Give a Fractional Rating in Approval or 0–10 Score:

Say the method is approval, and you want to give a candidate .7 maximum. Put 10 numbered pieces of paper in a bag, and randomly draw one out. If you’ve numbered the pieces of paper from 1 to 10, then approve the candidate if the number on the paper is not more than 7…that is, if the number is from 1 to 7.

If you’ve instead numbered the paper pieces from 0 to 9, then approve the candidate if the number you’ve drawn is less than 7. But suppose you wanted to give him/her .87 maximum? For this you want to number the pieces of paper from 0 to 9. Draw a number, and write it on a sheet of paper. Return the number to the bag. Shake the bag and draw again. Again, write the drawn number on the sheet of paper, directly to the right of the 1st number. If the number you’ve written is less than 87, then approve the candidate.

What if the method is 0–10 Score and you want to give a candidate .87 maximum? Do as I described when, in Approval, you wanted to approve a candidate with .7 probabilities. But here, you want to, with .7 probability, give the candidate 9 points instead of 8 points. So, (with the papers numbered from 1 to 10) if the number you draw is from 1 to 7, then you give the candidate 9 points instead of 8. Otherwise, you give the candidate only 8 points. Of course, if the papers are numbered from 0 to 9, then give him 9 points instead of 8 if the number drawn is less than 7.

4. Score Advantages:

Score’s more flexible ratings better allow the voter to do exactly as he or she feels. With the stark, all-or-nothing choice that Approval calls for, if the voter doesn’t make a good choice, then his/her choice might be really bad. But, in Score, the voter can give his/her best fractional estimate of what’s best and, not having to make the stark, all-or-nothing choice, a misjudgment won’t be as bad. I emphasize that the voter can give fractional rating in Approval too, probablistically, as described above, but fractional rating is easier in Score, built right into the balloting.

I used to criticize Score (and no doubt some still do), claiming that it encourages a voter to give fractional rating in a situation where his/her best strategy should (as described above) be an extreme rating, such as a 0 rating. I used to say that a more strategic voter could take advantage of him/her, by 0-rating his/her candidate. It now seems to me that that argument is fallacious: If the method were Approval, how do you know that that voter wouldn’t approve that candidate, giving him/her even more undue support? As I said above, the easy flexibility of Score would mitigate, soften, and minimize a voter’s misjudgments.

5. Approval Advantages:

First, as I said, in Approval you can give fractional rating, a fraction of max, probablistically, by drawing a number from a bag. How hard is that really? In a public election, with thousands or millions (or even hundreds) of voters, a probabilistic .7 rating, by a faction, is effectively the same thing as a .7 rating in Score.

And, as described above, under “Score Count”, Approval’s count is much easier and simpler than any Score count can be. Even the best and fanciest method (I consider Symmetrical ICT to be the best) won’t do you any good if the count is fraudulent. By that principle, Approval’s simpler, easier count is the all-important consideration.

If a voter wants to give fractional rating, it’s much better to give each such voter a little more to do than to give the counters more to do. That’s because one or more counters might abuse that greater opportunity for fraud. And what’s wrong with letting the fractional-rating voter have closer do-it-yourself involvement with that fractional rating that Score would have provided ready-made? Do we really need that ready-made luxury?

Approval and Score Election Bottom-line: Approval is the best, most advisable, and most feasible voting system proposal for official public elections.

Also see our entire section called Voting Methods Central.

ursamajor says

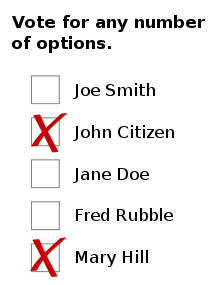

Both Approval Voting and Score/Range Voting are unconstitutional under U.S. law. They both violate the “one person-one vote” requirement as defined by the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Approval Voting example with the article is a perfect illustration of the violation if both marked candidates get this voter’s choices counted at the same time. It’s the same with the Score example if all three candidates get a number counted at the same time. And those things happen in those systems.

Michael Ossipoff says

ursamajor said:

Both Approval Voting and Score/Range Voting are unconstitutional under U.S. law. They both violate the “one person-one vote” requirement as defined by the U.S. Supreme Court.

[…]

[endquote]

ursamajor, you’re misunderstanding both the literal meaning of “1-person-1-vote, and its intent.

The term was coined in regards to districting disputes, when districting faults gave to some voters more voting power than others.

Approval doesn’t give unequal voting power.

In Approval, every voter has the equal power to rate each candidate, with 0 points or 1 point.

I refer you to my first article at Democracy Chronicles. Its title is “Some Problems with Plurality…” or something like that. You’ll find it in the list of articles at the bottom of any one of my articles here.

Plurality and Approval are both point systems, in which you, the voter, give 0 points to some candidates, and 1 point to others.

In Approval you, and only you, decide and choose which candidates rate a 0, and which candidates rate a 1.

Plurality has a peculiar rule, saying that you must rate all but one of the candidates at 0 points–even though you don’t consider all of them to be deserving of only a 0, instead of a 1.

Rating a candidate with 0 points, when you feel that s/he deserves 1 point is falsifiction. Plurality’s rule requiring that could be referred to as “Plurality’s forced falsification rule”.

Forced falsification has no place in a democracy.

What’s that you say? We’ve always done it that way? Right, and the same could be said of slavery, in 1864. If we keep a demonstrably undemocratic practice because we’ve always done it, then reform and improvement would be impossible.

Plurality’s forced falsification rule has a number of bad consequences:

l. It forces millions of people to completely abandon their favorite. Supposedly, in theory, people are voting for their favorite in Plurality. Oh yeah? Ask some Democrats if they’re voting for their favorite, or if they’re really just voting for a lesser-evil, to keep someone worse from winning. That Democrat voter will tell you that it’s necessary to abandon your favorite inorder to support the lesser-evil.

That problem doesn’t exist with Approval. With Approval, for the first time, everyone would be able to vote for, to fully support, their favorite(s).

What would be the result, if everyone were allowed to give a point to the candidates that s/he likes and trusts? Guess what: The winner would be the most liked and trusted candidate.

Does anyone claim that that would be a bad result?

2. Split vote. In Plurality, if a group of voters like candidates X and Y, but are divided between them, and they all despise Z, then, if they want to keep Z from winning, they must organize an agreement to all vote for X, or to all vote for Y.

But, in Approval, they can just approve (rate at 1, instead of 0, the candidates they like: X and Y. Approval has no split vote problem.

You’ve heard about rating things from 1 to 10. You may have heard about “point systems”, in which voters can rate a number of alternatives according to how good they are.

Approval is a point system, in which you can rate the candidates from 0 to 1. Score 0-10 is a point system in which you can rate the candidates from 0 to 10.

Neither violates 1-person-1-vote. Each person equally has the same power to rate each candidate as s/he feels that candidate deserves.

Michael Ossipoff

augustin says

“one person-one vote” equals “one person-one ballot”. Every body gets the same type of ballot and has an equal opportunity to express him/herself. This is a false problem.

ursamajor says

The requirement I meant* is about what counts as a “vote”. You’ve just restated what Mr. Ossipoff wrote about a voter’s “power”, which isn’t legally relevant.

* See my response 9/30, 10:36 pm, in the next string, correcting the constitutional principle I should have referred to. It should have been equal protection.

Adrian Tawfik says

Does a person who marks two choices have more of an effect on the vote than a person who votes for only one?

ursamajor says

Yes, if the two choices are counted for voter A and only one choice is counted for voter B. And that’s what would happen.

What Mr. Ossipoff doesn’t understand is that the constitutional issue revolves around what’s counted. In your example it’s different numbers of choices on the ballots. The “power” the voting method gives voters isn’t legally relevant to this test of a voting system.

Michael Ossipoff says

ursamajor says:

Yes, if the two choices are counted for voter A and only one choice is counted for voter B. And that’s what would happen.

[endquote]

…and who knows what that means. When you mark an Approval ballot, by giving all the candidates either an “approved” rating or an “unapproved” rating–either a 1 or a 0, your ballot marks are not counted for you, the voter. They’re counted for the candidates. If you approve a candidate, by giving him a 1, then that adds 1 to his approval total.

The winner is the voter who is approved by the most voters.

ursamajor says:

What Mr. Ossipoff doesn’t understand is that the constitutional issue revolves around what’s counted.

[endquote]

Wrong. The constitutional issue is the “equal protection under the law” clause of the Constitution.

That clause has (rightly) been interpreted to imply that some voters shouldn’t have more power than other voters.

And that correct constitutional interpretation has been applied to districting disputes in which a mis-districting has resulted in unequal power for voters.

ursamajor says:

In your example it’s different numbers of choices on the ballots.

[endquote]

Yes, in Approval, the voter is the one who chooses which candidate(s) s/he will approve. …which ones s/he’ll give 1 point to, instead of 0 points.

In Approval, each voter only has one vote on any one particular candidate. You can give to that candidate an approval or a dissapproval. One point or zero points.

But in a voting system that rates candidates, (as Plurality and Approval do) freedom requires that the voter be the one to decide which candidate(s) s/he will approve.

Every voter has the equal power to rate each candidate, to choose, for each candidate, whether that candidate should get an approval or a disapproval …a 1 or a 0.

ursamajor says:

The “power” the voting method gives voters isn’t legally relevant to this test of a voting

[endquote]

Wrong. The 1-person-1-vote issue was entirely about unequal voting power due to mis-districting.

Perhaps ursamajor would like to consider reading a little on the subject before giving his legal advice.

Only if ursamajor asks a different question, or gives a new argument, will I reply again.

ursamajor says

Mr. Ossipoff is partially correct, to the extent that I cited the wrong constitutional principle that Approval and Score voting violate. I should have stated that IMO they violate the equal protection principle because they would give some voters more choices that *count* than other voters.

The claim that by choosing to vote for two candidates the voter chooses to vote the opposite (0 instead of 1 or “disapprove” instead of “approve”) for the other candidates is Looking Glass logic. It puts the idea of “voting” on its head by saying that not voting is voting “not”.

Of course, neither Approval nor Score is used in any real-world political election in the USA. So — unlike Instant Runoff Voting which has been litigated and found to be constitutional — any opinion about them at this point is theoretical. When any of them is legislated into reality, we’ll see what the courts have to say.

(The “power” voters get is legally irrelevant. Please cite case law that contradicts that if you maintain it’s legally relevant.)

Michael Ossipoff says

ursamajor says:

Mr. Ossipoff is partially correct, to the extent that I cited the wrong constitutional principle that Approval and Score voting violate. I should have stated that IMO they violate the equal protection principle because they would give some voters more choices that *count* than other voters.

[endquote]

…and thanks to ursamajor for clarifying that it’s only in his own private opinion that Approval and Score violater Equal Protection.

Law has to be precise. Meanings have to be precise. To requote ursa major:

“…because they would give some voters more choices that *count* than other voters.”

That’s vague. Who knows what ursamajor means by it.

Every voter has exactly the same choices available. Every voter can approve or disapprove (give 1 point or 0 points to) any candidate.

Everyone has exactly the same power to do that.

Which part of that doesn’t ursamajor undestand?

In any voting system, including Plurality, you can cast a vote that “doesn’t count”, in the sense that it doesn’t instrumentally affect the election result.

For example, in Plurality, you can vote for Mickey Mouse. Many people do (because they don’t know that there are candidates who offer what they want).

In Plurality, if all of the progressives divide their votes between a large set of different progressive candidates, then their votes aren’t going to “count”, in terms of affecting the election’s outcome.

In Approval, they can make their votes count, if they approve all of the progressives, In Approval, even a highly-divided population-segment can make its vote count, as much as anyone else’s does.

So, sincerely-voting voters are much more uniformly and equally able to cast votes that count, in Approval, than they are in Plurality.

Does ursamajor really believe otherwise?

ursamajor says:

The claim that by choosing to vote for two candidates the voter chooses to vote the opposite (0 instead of 1 or “disapprove” instead of “approve”) for the other candidates is Looking Glass logic.

[endquote]

Vagueness is what ursamajor is about.

And no, I didn’t say that the voter necessarily _chooses_ to give 0 points to the other candidates. In Plurality, the voter is forced to give 0 to all but one candidate, though that often woudln’t be what the voter would prefer to do.

Approval is about giving the voter more freedom. Approval amounts to the repeal of Plurality’s forced-falsification rule (the rule requiring voters to give 0 points to all but one candidate, usually contrary to how they themselves would prefer to rate the candidates).

It’s a freedom issue. It’s a voting-rights issue.

Undeniably, Plurality and Approval are point systems, in which each voter gives 1 point to some candidates, and 0 points to the others.

The differnce between Approval and Plurality, those two point systems, is that in Approval, you, the voter have the freedom to choose to which candidates you give 1 point, and to which you give 0 points.

ursamajor says:

It puts the idea of “voting” on its head by saying that not voting is voting “not”.

[endquote]

In Plurality, not giving a point to a candidate _doesn’t_ mean intentionally, voluntarily, rating that candidate with 0 points. But it nevertheless does give that candidate 0 points, however ursamajor would like to word it.

Approval lets the voter decide.

Equally allowing everyone to rate each candidate, by giving him/her a 1 or a 0, doesn’t confer unequal power, and doesn’t violate Equal Protection. But of course there’s no point in ursamajor and I arguing that point. We aren’t the Supreme Court, and the queation isn’t before the Supreme Court, at the present time.

But if ursamajor, for the purpose of discussion here, wants to claim that letting each person give 1 point or 0 points to each candidate would violate Equal Protection, or in any way violate anyone’s rights, then he needs to justify his claim a lot better than he has so far.

Likewise for Score allowing each voter to give to each candidate anywhere from 0 to 10 points.

Changing from the Plurality point system, with its forced-falsification rule, to Approval would be nothing other than a granting of more freedom to every voter, a removal of an unjustifiable restricion of voter freedom.

ursamajor says:

Of course, neither Approval nor Score is used in any real-world political election in the USA.

[endquote]

All reform consists of things different from what was done before.

In some regards, sometimes the way things are done is fine. But sometimes the way things are done isn’t adequate, and, in those instances, something new and different. The repeal of Pluralit’s forced-falsification would be new. But it would nevertheless be desirable. The old way isn’t always better. Tradition isn’t always what’s best. That’s why slavery was abolished, for example.

ursamajor says:

(The “power” voters get is legally irrelevant.

[endquote]

Wrong. The application of Equal Protection to districting was about unequal voting power.

ursamajor says:

Please cite case law that contradicts that if you maintain it’s legally relevant.)

[endquote]

ursamajor is the one who is making claims about Constitutional law. Ursamajor is the one who is making claims about the constitutionality of Approval.

Then, if there are constitutionality rulings that agree with ursamajor on that, then let him/her cite them.

Perhaps ursamajor can point to a judged case, but I don’t know of a case in which the Supreme Court, or any court, has ruled on Approval’s constitutionality.

In other words, ursamajor is talking about…nothing.

If Approval is ever enacted somewhere, the Republocrats will likely try to oppose it in any way they can, because (I predict) better voter freedom would dump the Republicans and Democrats into the dusbin of history. So, most likely, there would be constitutionality challenges.

ursamajor has stated his opinion on that matter. I’ve stated mine, and I’ve told my justification for my statements. There’s nothing more to be said.

There is no court precedent either way.

It’s time for ursamajor and I to just agree to disagree.

Michael Ossipoff

ursamajor says

Mr. Ossipoff’s exchanges with other people have many salient features:

(1) He’s never wrong. He’s a legend in his own mind.

(2) He obfuscates with wordiness and detail that he often has to correct because he appears not to proofread his own posts.

(3) He redefines words, not unlike Humpty Dumpty in Through the Looking Glass: “When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.”

(4) He often insults the person he purports to respond to.

(5) He often ends by asserting that the other person must “agree to disagree” with him.

It baffles me how he expects people to come around to agreeing with him when he repeatedly does these things in argumentation. (See the Election Methods listserve for many, many examples of the five points above over many years.)

There’s little point in trying to engage Mr. Ossipoff unless a person starts by agreeing to #1 above.

Michael Ossipoff says

Adrian–

You wrote:

Does a person who marks two choices have more of an effect on the vote than a person who votes for only one?

[endquote]

No. Each person is rating the same number of candidates–all of the candidates. If I don’t approve a candidate, I’m still giving him/her a rating. I’m giving him/her a zero rating.

Suppose that voter A, wanting to have as much power as possible, votes for _all_ of the candidates. How much does he affect the outcome? Not at all. How much power or effect does his vote have? None.

Ok, then, suppose that, in a 10-candidate election, he approves 9 candidates. All but one. And suppose that you approve the one that he didn’t approve. Your ballot cancels his ballot out. He approved 9 candidates, and you approved one candidate, and your ballot cancelled his.

Michael Ossipoff

Michael Ossipoff says

Adrian–

Evidently ursamajor is angry because I said that there is nothing more to say, and that it’s time to agree to disagree. But his motivation is beside the point and irrelevnt–This post is only intended to ask about Democracy Chronicles’ policy regarding abuse of the comment-space.

As I understand it, the comments space is for comments regarding the topic of an article.

I wouldn’t suggest censoring anyone, not even ursamajor, who post on-topic.

But a post that’s entirely about someone with whom the poster disagrees isn’t even remotely on-topic.

Of course anyone can say whatever they want, relevant to the topic of the article whose comment space that person is using. …though when not saying anything new, they might not be replied to. Given his conduct, ursamajor doesn’t qualify for a reply, if he ever did.

But what is Democracy Chronicles policy about abuse of the comments space, as defined above in this post (posts that are entirely off-topic, and entirely about someone with whom the poster disagrees)?

Michael Ossipoff