Our country is solid, but no politician gets attention from making that observation. Threats of American ruin and our “collapse if (insert political rival) gain power!” are frequently shouted. They’re lying of course, with the imminent Drag Queen Story Hour apocalypse being an exception.

Our country is solid, but no politician gets attention from making that observation. Threats of American ruin and our “collapse if (insert political rival) gain power!” are frequently shouted. They’re lying of course, with the imminent Drag Queen Story Hour apocalypse being an exception.

But countries can and occasionally do collapse. It is exceedingly rare: even in revolutions with bloody shakeups, real change rarely means much more than one group of despotic mafias replacing another at the top.

For an example of real state collapse, though, there’s Cambodia. In 1975 the Khmer Rouge took the capital Phnom Penh, forced its million people on a one-way march to the countryside and executed the government, intelligentsia, and military. They destroyed property records, blew up the national bank and pretty much outlawed money as they sealed the borders of the state and threw out all foreign citizens. They hunted and killed, almost completely, ethnic minorities.

Another spectacular collapse was the defenestration of Somalia in 1991. After years of haphazard violence, the Somali state utterly collapsed. The new militia bombed a far-off province, which succeeded (“Somaliland”) and devolved until all organized governance was lost leaving Mad Max style gangs of turf fighting Qat-crazed warlords. Blank Somali passports were sold in the marketplaces for $50. That’s collapse.

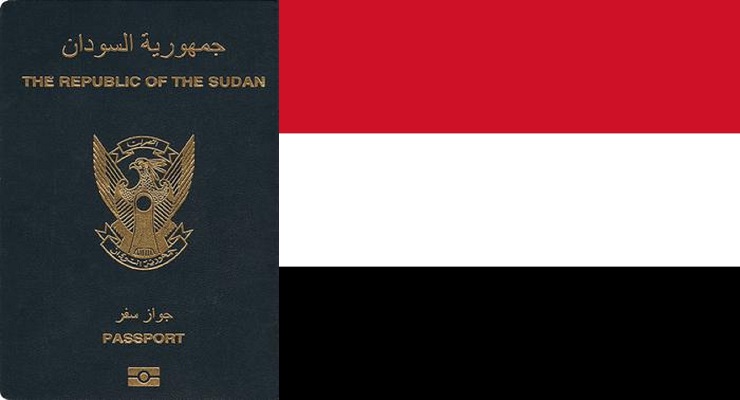

Which brings us to today. Sudan, like it’s sad, dusty progeny The Republic of South Sudan, are on the precipice of being failed states. Hopelessly poor, they fall at the bottom end of most metrics of human flourishing.

These dysfunctional and corrupt disterlands barely get by at the best of times. The current machination there could easily lead to full state collapse.

Further, the presence of the Russian Wagner Group chasing Sudan’s gold can only push them further into disorder: having Wagner in your country is like bed bugs in your sofa or lice in your scalp: ugly, destructive and hard to expunge.

Things can be dicey for foreigners unwilling or too stupid to get out of the way and leave. In both Cambodia and Somalia, they fled, the final holdouts (diplomats and journalists, mainly) were kicked out or killed.

It is in these chaotic circumstances where the color of one’s passport is utterly vital.

A British law firm, Henley, rank passport “strength” by country, all 190 or so of them. As you’d expect the “strongest” countries’ passports are the richest with Japan, the EU, US, Australia etc. routinely being top.

That “strength” means the number of countries one can visit without a visa, but even visiting with a visa is a bit of a misnomer. For “strong” passported citizens that usually means the mild inconvenience of a visit to an embassy (or via post), a fee, photo and some waiting. Nearly all wealthy countries don’t even require visas from rich world citizens.

But for citizens of “weak” passport countries, life is very different. The weakest passports are from poor or hooligan countries like Afghanistan, North Korea, Pakistan, or Iran. A tragedy in the shape of a nation, Lebanon, ranks nearly last. GDP is the main predictor and geopolitics is the main decider of where one’s country ranks. Overstay rates of citizens also figure in.

Of course, such impediments to travel are the same at any time, but when you REALLY need to escape a collapsing country, it marks the difference between life and death.

Locals (Sudanese, Somalis, and Cambodians in the above cases) have nowhere to go, if they even have passports at all. Routinely, passports in “weak” states are very difficult to obtain (poor governments actually routinely run out of paper stock), or large bribes are needed, months waiting, and huge expenses entrap much of the world’s population inside their countries’ borders.

The alternative, to leave without papers is an act of terrible desperation. The Upper Nile/Sudan and the Central African region already host, within their swampy borders over a million refugees living for years, decades or even generations in hellish camps from Congo to Somalia.

Even for the rich elites of the Third World acquiring visas almost anywhere is a trial. For example, a few years ago 70% of wealthy Bangladeshis applying to visit the US as tourists were turned down (most without reason). They failed the almost getting-into-college-level in person interview at our embassy in Dhaka for even a trip to Disneyland. Refusal rates at all U.S embassies are published and they’re huge in “weak” capitals.

As well as freedom, drinking water, unpolluted cities and food, electricity, a justice system worth its name, we take freedom of international movement for granted in the West. For much of humanity though, national borders are prison walls forever entombing their unlucky inhabitants: in good times and when a country collapses.

Leave a Reply