Michael Mariani

When peaceful protests intensified in the Syrian city of Daraa on March 15, 2011, no one knew exactly what this so-called “Cradle of the Revolution” would rear. That it would displace over two million people, making them refugees in countries like Jordan, Egypt, and Turkey, and others dispossessed between their own borders. That the revolution’s death toll would climb north of 90,000, largely composed of innocent civilians. Or that seemingly each week, the civil war would itself rear another gruesome atrocity, like the discovery of over 100 bodies in a canal in Aleppo. Nobody could have foreseen that what began much like the other waves of the Arab Spring would crest into something else entirely, sucking everything up—children, families, homes—in its indiscriminate undertow.

There was a time when the protesters, and by extension the Syrian people whose rage and frustration they channeled, could see the change they wanted in their country clearly. They wanted an end to the half-century-old emergency law that gave President Bashar al-Assad autocratic power; a reinstatement of basic civil rights; and an end to pervasive government corruption. Probably above all, they wanted to begin carving a path to democracy.

There was a time when the protesters, and by extension the Syrian people whose rage and frustration they channeled, could see the change they wanted in their country clearly. They wanted an end to the half-century-old emergency law that gave President Bashar al-Assad autocratic power; a reinstatement of basic civil rights; and an end to pervasive government corruption. Probably above all, they wanted to begin carving a path to democracy.

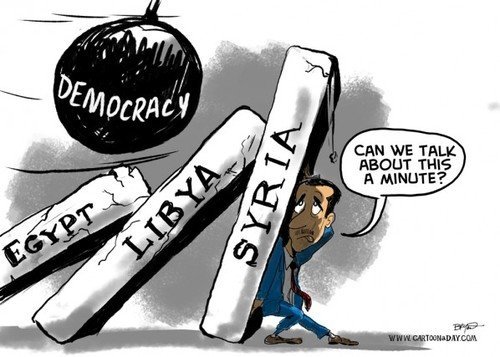

In 2013, 23 months since the war began these political goals no longer even seem to be a small part of the war. They are near-irretrievably buried under the soot, ash, debris, and corpses scattered throughout the country’s ubiquitous battlegrounds. The problem with revolutions (at least the ill-fated ones) is that what appears transcendent at first—ideals, progress, freedom—rapidly vanishes when the stakes shift from the ideological to the corporeal. This inevitable disillusionment, repeated throughout history, is incarnated anew in Syria. For Syrians now, the journey to democracy and freedom is so cruel, complex, and tumultuous that it makes them wonder whether it is really a journey worth taking at all.

In early 2011, the Arab Spring had reached its unstoppable apex. Protests, uprisings and bursts of civil war were raging in Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya. Although the Syrian people were quiet at first during these insurrections, even being referred to as the “Kingdom of Silence,” their dispassion would not last long. After all, they had as good a set of reasons as any to rage against the tyrannical machine. For almost 50 years the country has existed under emergency rule, a legal state one rung beneath martial law that gives government forces unconditional power to arrest and detain its people.

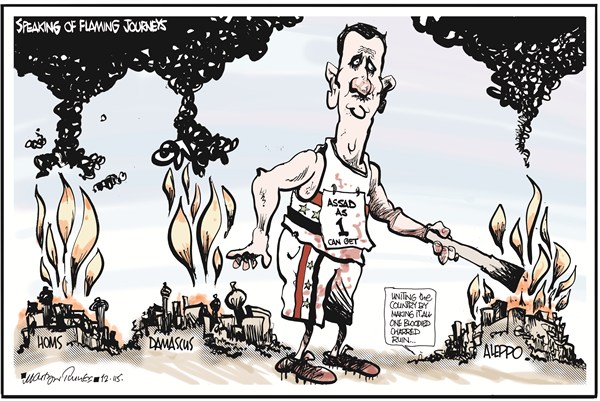

Syria is run by a one-party government without free elections: if citizens do not like the current government and policies, they can do exactly nothing about it. Since Assad came to power in 2000, Syria has imposed crippling censorship and freedom of speech restrictions, and used its emergency rule to imprison and torture political dissenters. All told, this is a regime that dropped an iron curtain on any hopes of democratic progress. Such a despotic president certainly explains the revolution and ultimately civil war. But where does that line of justification end? And more importantly, when does that initial justification become so smothered by death, anarchy, and sectarian bramble that it is no longer exists at all?

Syrian Democracy Tactics

Ironically, the greatest blight on the Syrian people at this very moment may be the very soldiers trying to liberate them. The Free Syrian Army (FSA) was officially formed in July 2011, and has grown fiercer and more formidably armed since its inception. While their diffuse, guerrilla tactics have been moderately successful in chipping away at government-held territory, it’s that same unpredictable fragmentation that has been so detrimental to civilians. Simply put, the FSA is not a unified force. It is made up of remote legions that include volunteers, army defectors, and militant groups. As such, it is free-ranging, undisciplined, and vulnerable to exploitation.

In recent weeks, Syrians have grown disillusioned with the FSA, recounting how rebels have instituted their own scrappy, bare-footed tyranny: they are known to cut to the front of bread lines, seize expensive cars, and detain civilians on a whim. Rebel commanders say the lack of regulation with the FSA inevitably leads to opportunists and parasites, but that these fighters are exceptions. They all claim to serve the revolution and the liberation of Syria, but the longer the war drags on the further obscured these principles become. With no government, dwindling resources, and rampant displacement, Syria is nearing a Darwinian state. Although the rebels may have the people’s best interests in mind in the long term, the short term has become a time of hardship and squalor for the helpless masses.

In recent weeks, Syrians have grown disillusioned with the FSA, recounting how rebels have instituted their own scrappy, bare-footed tyranny: they are known to cut to the front of bread lines, seize expensive cars, and detain civilians on a whim. Rebel commanders say the lack of regulation with the FSA inevitably leads to opportunists and parasites, but that these fighters are exceptions. They all claim to serve the revolution and the liberation of Syria, but the longer the war drags on the further obscured these principles become. With no government, dwindling resources, and rampant displacement, Syria is nearing a Darwinian state. Although the rebels may have the people’s best interests in mind in the long term, the short term has become a time of hardship and squalor for the helpless masses.

The heterogeneous FSA is also composed of darker, more opaque forces. Since at least January 2012, jihadists and Islamic extremists with links to Al Qaeda have been fighting alongside Syrian rebels. On the 23rd of that month these extremists formed the Al-Nusra Front. The militant group consists of Sunnis and jihadists and has been a ferocious weapon for the rebels. For our part, the United States government declared them a terrorist organization in December. However one perceives them—and there are many ways—there is no doubt that they are a thickening agent in this entire conflict, mucking up ideologies, sectarian battle lines, and prospects for the future of Syria.

The most alarming reality about the participation of Al-Nusra is their ambition to form a post-Assad state under Sharia law. Their broader aspirations are very similar to those of Al Qaeda: They want to unify Muslims under a Pan-Islamic state that encompasses the Middle East, much of North Africa, and, God willing, the world. Clearly this element is ripe for fear-mongering and terrorism dread, but there are more imminent ramifications as well. If the rebels should triumph and end the Assad regime, what will become of Syria? Will the Syrian National Coalition provide the necessary ballast and steer the precarious country toward a democratic government? Or will Syria succumb to the ideological anarchy it is already showing signs of, exacerbated by the natural friction of population density, and plunge into a failed state? All we know is that in the long term, Al-Nusra does not serve Syria or its democratic ambitions. It serves Allah, and in extremists’ devotion to Allah, they have flown like flies to the wounds of wasted nations, looking to erect Sharia among the ruins.

In Syria, there is an agonizing present and an uncertain future. Disease, death, and displacement are rampant and entirely unchecked, and as doctors flee and hospitals shut down, circumstances will only get worse. This country’s burden comes not only from the fight for liberation—the human casualties, loss of infrastructure, and dearth of basic resources—but from liberation itself. If President Assad is successfully ousted, the Syrian National Coalition would theoretically assume power. But an expatriate provisional government with inconsistent support (at best) from within Syria is a recipe for further instability. What’s worse, individual sects and ethnic groups will no longer be unified against a common enemy, causing larger and more dangerous fractures. It is all a very steep price to pay for a democracy that is far from guaranteed.

Alas, we can never ask whether all the death and destruction is worth it; sacrifices come easier than answers in the Middle East. The only thing the international community can do is provide the means and aid necessary to end the civil war. The United Nations and its most outspoken constituents cannot presume to know the solution to sectarian conflicts, the ideological implications of the jihad presence, or how to reach a consensus for the future among the people of Syria. Those are the inheritances of the future sovereign state. We can only ease the terrible burden of liberation.

Leave a Reply