An Anecdotal Journal by Julio César Guerrero, MSW, MA

When Julio César Guerrero wrote a guest post a while back, I promised you the back story of the months of planning for the Caravana43. I know that many of you have already read much about Ayotzinapa. But now — as we near the anniversary of the disappearance of the 43 students from Ayotzinapa on September 26 — we have much planned, including presentations of a documentary film with English subtitles that concern the atrocious acts of cowardice enacted in Mexico. The film is called Ayotzinapa, Chronicle of a Crime of State. Please write me if you are interested in knowing how to show this film near you.

As promised, however, here is Julio César’s account of the weeks of preparation and activity from beginning to end, as well as his recollections of the actual process of planning this monumental task. Although this is a condensed version of the original Spanish, he wanted to give you the highlights.

You will learn a lot!

© Fanzine Detektor

So if you are an activist, if you believe in justice and freedom, if you want peace within our nations and real solidarity to exist, then I strongly encourage you to read Julio César’s comprehensive testimony of his weeks with the caravana.

And if you still feel the need to do something more, join one of the many social justice groups that may have developed from our presence throughout the country, since we know that Caravana43 was only the beginning and catalyst of our fundamental work.

I am sure you can seek these groups out, because Caravana43 laid out the seeds.

But it is now our turn to nurture these seeds and make them grow.

¡Todos Somos Ayotzinapa!

INTERNATIONAL COORDINATION OF THE CARAVANA43: An Anecdotal Journal

by Julio César Guerrero, MSW, MA

Checking my email, I found a message I sent out on November 11, 2014, proposing the idea of an international solidarity project for the parents of the 43 forcibly disappeared students from Ayotzinapa on September 26, 2014 in Iguala, Guerrero. The idea came about after my visit to Mexico City in October 2014, when I participated in a couple of marches to El Zocalo (Mexico’s Central Plaza), supporting the parents of the forcibly disappeared normalistas (students from the Raúl Isidro Burgos Rural Teachers’ College).

The display of popular unity the parents of these student teachers generated everywhere they went gave me the idea of extending such support to the United States, something that has become a tradition for the human rights and trade union groups, especially after the enactment of the free trade agreement (NAFTA) in the mid-nineties. The previous year I had coordinated a support caravana for a group of Braceros traveling from Texas through the Midwest that culminated in Washington, DC and New York. I took this idea and adapted it, proposing the same support plan for the Ayotzinapa group.

Having worked during the nineties coordinating international solidarity projects, I called several of my contacts in Mexico for assistance. I asked them to help me get in touch with the group of parents to propose this project. The task of communicating with the parents turned out to be somewhat complicated and not as quick as I first thought it would be, due to the hermetic and inaccessible nature of the parents and their high political profile.

Finally, after several weeks of hard work in Mexico, I received a phone call from the group of parents. We exchanged impressions on the project, but not before they thoroughly interrogated me, making sure the invitation was legitimate and the project feasible. In the end, I was informed that my invitation was consistent with their plans to seek support outside of Mexico, since they had already received invitations from several Latin American countries and Canada as well. We then agreed on a plan to visit various communities in the United States and finally culminate the tour in Washington, DC and New York, two cities of great political importance at the international level. The modest project, which was originally only going to cover ten U.S. cities, would quickly be extended to three caravanas that covered most of the national territory from North to South and East to West, as the popular chant goes.

I visited New York in December to promote the project, given the obvious importance the group of parents had expressed of New York City being the merging and concluding place for the threecaravanas. Other than that, most of the coordination was done by phone and email. Moreover, the organization in the United States grew almost on a daily basis due to the demand from every region of the country, as well as Canada.

© Ana M. Fores Tamayo

I refer to this project as ‘intergenerational’ based on its organic constitution. Allow me to explain: when I first proposed the idea of the caravana, I called on colleagues from other projects with whom I had worked during the decades of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s (first generation). They in turn recommended to me other people they knew and trusted (second generation), and then came the people who called me of their own initiative and were added to the project, based on their commitment (third generation). This implies the interaction and collaboration among organizations and activists of various and different political orientations and numbers of years of experience in civic action (many who never even knew each other).

The proposed plan for coordination and support was very basic and simple to develop by the coalitions, which included a standard program of activities such as a press conference, a rally in front of the Mexican Consulate, presentations at universities, churches or unions, and with municipal, state, and federal legislative bodies, but not to include any support references from political parties. The plan was also very easy to coordinate from the perspective that the struggle for justice in Ayotzinapa did not belong to any one person or organization, so the most viable approach was to call a community meeting to form coalitions in each city that would facilitate the implementation of activities.

Another good reason to create coalitions was the strength that each participating organization might bring, or the diverse range of resources and styles of activism each might effectuate. Typically, coalitions are structures that come together to address a common issue or — during a state of crisis — these organizations of divergent political and ideological inclinations forget their differences to tackle a common problem. Therefore coalitions are organisms of limited time-span and tend to dissolve once a campaign ends, but at least these participants had the opportunity to get to know each other better and possibly form alliances more easily in future campaigns.

© Fanzine Detektor

With that in mind, I thought it would be important to give credit to the community based organizations that participated in and supported the Caravana43 coalitions. To that end, we identified close to 500 organizations at the national level. It is important to point out that based on the caravana presentations, university groups formed a strong component of these coalitions, followed by religious groups and less from unions or workers’ organizations.

The demographic composition is a strong consideration in the interaction of participants in any effective campaign. Because of this, my communication was entirely in English originally, since I knew that bilingualism is more prevalent among Latinos. Add to this the fact that most of the members of the first generation were Chicanos or Anglos, while the majority of the second and third generation activists were Mexicans and Latinos. Gradually, however, communications turned from English to Spanish, and by the end of the project most of our dealings were entirely in Spanish. A key factor was the inclusion of the people from Mexico in the organizing process.

Organizing a project of such magnitude and its political aggregate became a slow operation, particularly working with people from the second and third generation, since they had no knowledge of my work as an organizer and had obvious questions concerning the coordination process. Some of the people I talked to even showed some reproach, since they already had communication and ongoing support programs with Ayotzinapa, were natives from, had relatives in Guerrero, or were even graduates of theRural Normal Academies. My response was that neither I nor anyone could claim ownership of the struggle for justice of the parents of the forcibly disappeared normalistas, and the caravanas would help us all work together, united as one.

Supporting the movement born in Ayotzinapa eventually resulted in the adoption of the group of parents of the 43 missing normalistas. Many of the Caravana43 coordinators expressed interest both in the personal needs as much as in the social and political issues the group of parents faced. One of the concerns was the state of health and physical ability and conditions of the group, so I requested the medical history of each of the members.

My conceptualization of Caravana43 was a populist project. As such, I saw the solution to health care at the Barrio level. In other words, make use of local community resources to address any health problems that might come up along the way, such as community clinics, public programs in hospitals, or professional medical people within our families and friends. After all, this is one of the benefits of working within a coalition.

This openness facilitated the following collective proposals. Economic support: to have each coalition or city economically adopt one of the 43 families for an equal distribution of support. Political support: to develop strategic campaigns to denounce the attacks in Mexico against the movement of the parents. Tactical coordination:to arrange meetings between the Ayotzinapa parents and African American and indigenous organizations of parents whose children had been killed by police.

@ Ana M. Fores Tamayo

Although in several cases coordinators shared my vision of the Barrio approach and indeed, health care was obtained in this manner within their communities, most of the coalitions favored the purchase of a health insurance, probably to simplify the process and not to worry about the cost. The problem with buying health insurance turned out to be a bureaucratic and logistical headache, however, because it would have to be processed on the internet, and it was impossible to find an agency that sold insurance to ‘tourists’ that covered ‘pre-existing’ conditions. As a result, we acquired no insurance policy, which created ambivalence in some coalitions. We were thus unable to solve many health issues, causing difficulties that came up more frequently than anticipated.

To me, Caravana43 was a “sun up to sun down” campaign, encapsulated within a specific period of time. Moreover, the caravanas project began when the parents crossed the border into the United States and ended as they returned to Mexico.

From that point onward, it was a matter of developing a plan for a continuous support program based on the political and social capital created by Caravana43 during our journey together, but that would be another project. For the time being, the focus was the coordination of the three caravanas.

The study of the “new social movements” theorizes that since the civil rights movement from the middle of the last century, a new stream of social movements developed on par with the need or demand for structural change. These new social movements are characterized by their populist nature, detached from institutions, without official or regular membership and an absence of political ideology, such as communism, capitalism, Marxism, etc.

The design of Caravana43 adheres to such characteristics, which implies a non-hierarchical structure with entirely horizontal relationships based not on symbols or merits of authority but on collective commitment, solidarity, understanding, support, and tolerance. This was something difficult to establish, considering that many of the members of the national coalition had never worked together or even knew each other.

Therefore, the hegemonic tendencies of working within a conventional organization, under a vertical structure, and secured funding guaranteeing the budget of each move of the project created questions, doubts, and desertion among some members. On the other hand, Caravana43 offered an open forum where all the coordinators and their opinions had the same importance, where their ideas and proposals could flow freely without opposition, questioning, or debate.

This openness facilitated the following collective proposals. Economic support: to have each coalition or city economically adopt one of the 43 families for an equal distribution of support. Political support: to develop strategic campaigns to denounce the attacks in Mexico against the movement of the parents. Tactical coordination:to arrange meetings between the Ayotzinapa parents and African American and indigenous organizations of parents whose children had been killed by police.

And so it was that thanks to the great work of the Mexico support team and the solidarity of many activists on both sides of the border, we ended up covering all the details to start what would be the largest Latino-based initiative in recent years. To that extent, in only three months Caravana43 was able to leverage the support and endorsement from about 500 organizations in the United States, conforming 43 coalitions that covered close to fifty cities and 17 capitals in 21 States.

This notion is twofold when we include the coordination of activities on both sides of the border and its subsequent complications. Such a process included a support team in Mexico that for many of us will remain in anonymity but without whose help it would have been impossible to carry out Caravana43. They handled the necessary information for the visa applications and international flight schedules. From collecting all necessary information, which entails traveling from Mexico City to Ayotzinapa several times per month, and then transcribing and archiving such information for use in the digital form on the Embassy website, this work could not have been complete without the Mexico team on the other side.

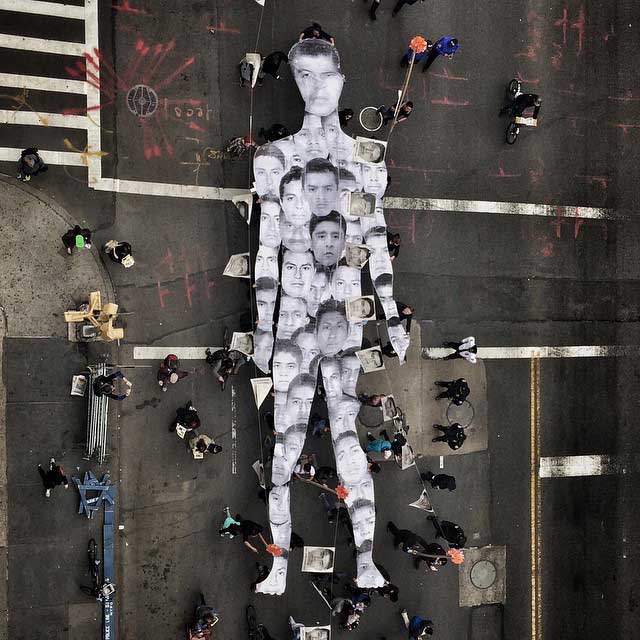

After 6 long weeks of taking Caravana43 on the road, the journey concluded on Sunday April 26 in New York City, where members of the three caravanas marched with the support of an estimated one thousand people from every region of the country. The project gained such an unprecedented momentum that it actually inspired similar undertakings in the European continent, Canada, and Latin America. Thus the gains can be measured in a number of ways: organizationally, politically, and economically.

Organizationally, Caravana43 served as a catalyst to inform, educate, politicize, and mobilize hundreds of thousands of individuals about the social and political conditions under which the 43 Ayotzinapa students were victimized. Many of the organizations under each coalition engaged in civil disobedience actions, held public forums, community meetings, vigils, and press conferences to keep their communities engaged on the issue. During this process of outreach, networking and coalition building was done with a diverse core of community, labor, grassroots, and faith based organizations, as well as with colleges and universities.

Politically, it can be safely said that Caravana43 impacted the press and political institutions in the United States by virtue of getting the attention of mainstream, alternative and social media, and rallying the support of Church, higher education institutions, unions, legislative bodies, publicly elected officials, and the community at large.

This can be proven by the Caravana members’ participation and testimony before the Amnesty International Human Rights Conference in Brooklyn, New York, the InterAmercan Commission on Human Rights in Washington, DC, the Hispanic Congressional Caucus in Washington, DC as represented by Congressman Luis Gutierrez, the California Federation of Teachers Convention in Los Angeles and before the United Nation’s Commission of Indigenous Women’s Rights, and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in New York City. At the same time, there were a number of lobbying projects and activities to get municipal and state governments such as the Texas State Assembly, Michigan State Capital, and New York City councils to name a few, to recognize and support the Ayotzinapa parents’ movement, which sought justice and answers from the Mexican government.

© Enrique Davalos

Financially, Caravana43 was extremely successful as well. Although this project was originally not intended as an economic aid but was meant more as a political and educational program, we estimated at the beginning that — after paying all expenses — we would be able to send at least $10,000 to the parents’ fund in Guerrero. As it turned out, it looks as if we were able to send out six times or more what we had originally expected.

As I said farewell to the group of parents on April 28 at the John F. Kennedy Airport in New York, they left with a great feeling of accomplishment and deep gratitude for all the support and solidarity they had experienced first-hand.

And as part of the follow up work, some at-large membership created work groups to continue the support after Caravana43 completed its tour to build on the social and political capital developed during this great time. These working groups are still in progress.

About the Author

Julio César Guerrero earned a Master’s degree in both social work and telecommunications at the University of Michigan. He spent many years teaching in the Michigan University system, where he developed ample experience in student services, classroom teaching, community organization and development, social and human services, nonprofit and human services administration, community and media relations, diversity training, outreach, and recruitment.

As a pioneer in bilingual community radio, he participated in the development of KDNA and Radio Cadena National News in Washington State, KUFW-Radio Campesina for Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers in California, and KRZA-Radio Raza in Colorado. He also worked as a program director and producer for KPFTPacifica Radio in Houston, KBBF in California, KUAT in Arizona, and WKAR in Michigan.

Under the role of community organizer, he participated in several educational events with union workers and human rights activists throughout the Midwest and Mexico, coordinated tri-national conferences for education and telecommunication workers from Canada, US, Mexico, and France, as well as the 2010US Social Forum, and finally coordinated some of the largest Latino workers’ leadership conferences for the Institute of Labor and Industrial Relations at the University of Michigan.

Most recently, Julio César Guerrero worked nonstop as the national coordinator for Caravana43, an international support network for the Ayotzinapa families of the 43 forcibly disappeared students in Guerrero, Mexico, when they made their tour through the United States.

Leave a Reply