This is the last of seven posts on Electoral Strategy. See the rest here.

It’s what we do that matters.

The rank and file of the social and labor movements hold the most important position and bear the heaviest burden of all. Participatory democracy is the key to reconstructing representative democracy. The labor and social movements have the power to change America.

I am not suggesting that activists shift their work to electoral politics unless they want to. It may well be that the best thing people can do is to build their movement and community. Make their organizations and neighborhoods more sustainable, more effective, more democratic and more disruptive to the normal course of corporate power.

We are in desperate need of grassroots rebellion and empowerment on many fronts and for many reasons. And, the social movements remain the best source of people with the capacity to undertake electoral work as transformative project.

The Greens have distilled popular oppositional politics into a compelling platform, but they did not invent it — decades of struggle from many social movements did.

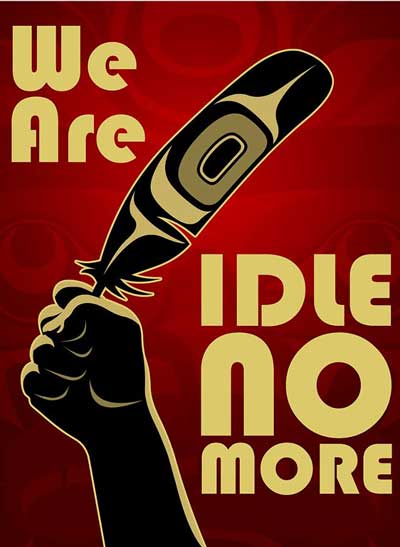

In our time, the struggle of low wage and contingent workers is mustering new people and new ideas in the pursuit of economic democracy. Occupy reshaped popular discourse and mass perceptions regarding class realities in America and rediscovered the promise of participatory democracy. Ferguson and #BlackLivesMatter brought racism roaring back into national consciousness and trained our eyes on the penal system and mass incarceration. The environmental movement, from Idle No More, to Food and Water Watch to 350 have found a diverse mass activist base that is trying to wake us up and tell us what time it is.

It is too late for horse trading. Too late for more of the same.

It is too late for horse trading. Too late for more of the same.

The power of the social movements to alter elections is largely based on our ability to disturb the peace. Beneath the often reported signs of contest and competition, the major parties enjoy a kind of power-sharing arrangement. Gerrymandering, regional strongholds, machine politics and the many legal limits on political competition have created something akin to a dual one-party system. Each party is master of its own domain.

Our power originates in our ability to disrupt and threaten triangulation, upsetting the harmony that allows the corporate power, empire, mass media and the penal system to remain untouched. Ramping up our ability to organize and conduct massive non-violent civil disobedience and protest is essential. Without a vigorous outside movement all the inside efforts will weaken or collapse because no there is no alternative, no credible threat of exit, no standard to refer to.

This is not necessarily an endorsement of loosely defined tactics that simply disrupts random motorists, although that seems a popular choice. Aim at a constituency with movement building in mind — not just some vague public. Do not surrender your communications to be carried — one way only— by the corporate media. We need to upset the system in ways that brings us into direct contact with the people we want to organize and mobilize. How else can we learn from them?

If you are not part of the solution you are part of the problem.

We do need to stare straight at the most glaring contradiction of the social and labor movements. While the movement has the potential to provide the spark, most established organizations representing workers, women, GLTBQ, students, people of color and the peace and environmental movement are often the most wedded to the Democrats and conventional political wisdom of “get in early” or lesser of two evils. And, much of the urgency and innovation of recent unrest has fallen on deaf ears of those in command of social and labor organizations.

The AFT’s premature endorsement of Clinton is a case in point. Sixteen long months before the election, a small group of union officials repeated the old standard strategy of “get in early.” What did we get in return? Does getting in early increase leverage or surrender to triangulation?

Thirty years of the corporatization of education should have taught us a few things. First, that the assault has come from mainstream Democrats as well as from Republicans. Both parties have slashed education budgets and undermined the status and compensation for teachers.

This bi-partisan consensus hides the deep structural consequences of corporate domination while shifting blame to teachers and students.

“Running it like a business” demands lower wages and contingent work, unprecedented student debt levels for higher education, high stakes and standardized testing, greater centralization and routinization of curriculum, and the punitive discipline of entire school systems just to name just a few corporate reforms. Meanwhile the real culprits of soaring childhood poverty, institutionalized racism, the school to prison pipeline, the disruption to family life caused by falling labor standards, chronic unemployment and low wages are invisible to corporate “reformers.”

In other words, the problems of education are the same problems we all face when our economy and government serve the corporate power and not the people.

Can this be reversed by the early and uncritical endorsement of one of the architects of the system? The AFT’s endorsement signals either that the union is an “easy mark” and/or consider itself to be part of the system.

An effective inside/outside strategy would have at very least included a national discussion and voting by the members of the AFT. But union managers too often fear disruptive politics even though it’s the only real leverage unions have ever had or ever will have. At its very best, getting in early is a receipt for limited concessions at the price of the ongoing corporatization of education.

The Fight for 15 has had more influence on electoral politics than any deal made at the top.

The real leaders.

There is a real saving grace here: we the people and the many thousands of solid union members of the AFT will have their say. Many will vote for Sanders or the Greens or offer critical support to Clinton contingent on some real agreements. Remember that in October 2007 the AFT endorsed Clinton early too. After the people and members had their say the national officers relented but apparently learned little from the experience.

How can this unresponsiveness to “we the people” be seen outside of the long slow decline of labor or the defensive posture of the official social and student movement organizations? And, what is the remedy outside of the challenging work of grassroots activism, participation, organizing and dissent?

What better example than the case of “Mayor 1%” himself, Rahm Emanuel. Emanuel is a longstanding leader of the Democratic party with deep connections with both the Clinton and Obama administrations. He is an unswerving servant of Wall Street and former financier; a major proponent of expanding the drug war and an architect of mass incarceration under Clinton; he also led the charge to cut welfare for the poor using austerity arguments later aimed at public employees, teachers, students and well, everyone.

Emanuel is one of the strongest proponent of triangulation consistently pushing national politics to the right by supporting pro-war democrats and cheerleading for the war in Iraq. He tips his hat to abortion rights, gay marriage, and gun control giving just enough to win support for his core mission of corporate power. No wonder the corporate media loves this guy praising him, amazingly, as a liberal courageously “not pandering” to special interests.

Even in defeat, the challenge from Jesus ‘Chuy’ Garcia showed how unstable triangulation is becoming. Garcia was a relative unknown and a working-class immigrant from Mexico. Even without money Garcia was a threat because the campaign stood on years of movement building and organizing. Amisha Patel captures it perfectly:

What Chicago’s various social movements have built did not materialize over the course of one election cycle and cannot be understood as just a set of electoral strategies, clever tactics or shrewd messaging. For years, Chicago has been an epicenter of militant, grassroots organizing that has come to deeply resonate with working class families. A long-term transformative vision lies at the heart of this organizing, taking aim at oppressive systems and corporate interests that exploit and divide people along lines of class and race.

Well, there it is. Can we take the Chicago model national?

In sum.

The political system is a human artifact that will respond toward the direction of power. A stronger, larger movement will increase our capacity to pull, push and pivot all along the line — from you local union or community group to the insider working to wean the Clinton machine away from Wall Street.

The point of the proposed strategy is not to find the perfect candidate or political purity but to create a strategic framework to assess and guide our activism. Instead of endless debate, we should express our “truth” through the political work of building “truth-power.” [1]

Speak truth, yes, but in the language of power. Without movement building, without an inside/outside strategy we can not expect the inside work to yield results any different from the past.

It is hard to know how long triangulation and minor concessions will maintain order. It is very likely that the crisis will deepen on every front making the risk of conventional behavior greater than the risk of independent, creative action.

This much we can be assured of: history has not come to an end.

Yes, it is unlikely that electoral work alone will lead to social transformation but it is an important arena — an opportunity we cannot afford to abandon. Transformative politics move us toward “both/and” options not “either/or” choices.

Long ago in a time of sweeping change, social movements and third parties upset and transformed the American electoral system. Then came the Civil War. Given the choice of revolution or disaster, the Party of Lincoln embraced the rebellion of runaway slaves and followed the leadership of freedom fighters, black and white, to destroy slavery. Lincoln’s actions were first and foremost strategic and political but helped make a revolution. With all the failures of emancipation and Reconstruction, there was no going back.

We could do far worse. And maybe far better.

[1] Gandhi’s innovative use of non-violence was to fuse politics to love or moral truth. He called the concept of satyagraha. Satyagraha is love-force or truth-force which the American civil rights movement revised into soul-force. The civil rights movement spoke truth to power but in the language of non-violent force: sit-ins, occupations, marches, strikes, picket-lines, boycotts.

Leave a Reply