We all want MO. We all need MO. And this is how to get MO.

We all want MO. We all need MO. And this is how to get MO.

First, what is MO, or, more appropriately, the MO?

The MO is, by definition, what you most desire, what you most want.

Not “you” personally, but “you” collectively. It is what the group, the team, the family, the tribe, the community, the state, the nation most desires. It’s the policies we, as voters, most want the government to adopt; the direction we most want the nation to go in; the candidates we most want to elect. The MO is the Majority Opinion, M – O.

We don’t create or construct or build the MO. We reveal the MO, uncover the MO, discover the MO. With any group of people and any set of options, the MO already exists; we just have to find it.

How do we find the MO? This is where it gets really easy. We ask the members of the group.

Is it impossible to ask a person to identify the option(s), from a finite set, he or she most desires?

Imagine I ask you (personally) which of these five cars you most desire. You might think, “I like the color of this one the most, but I like the gas mileage of that one the most. But I also like the power and looks of that one the most, but I don’t like that one due to the reliability.” You make comparisons and then pick the car(s) you most desire after going through your own personal internal dialogue. But outside of your own mind, we only hear the result, your final decision.

Is it ridiculous for a group to identify the option(s), from a finite set, that it most desires?

A group can use the same method as an individual did to identify its favorite options, but it must start with that same internal dialogue. In other words, we can’t start with each individual of the group’s final decision, but must have everyone externalize their internal dialog (how much they desire each option) so that we can combine each individual’s level of desire.

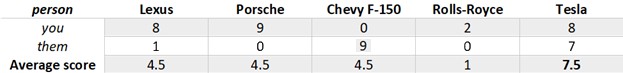

For example, suppose you’re in a group that consists of only two people. The group wants to find the car(s) it most desires. You may most desire a Porsche and the other person may most desire a Chevy F-150. But which car does the group most desire? And how do you determine that? Do you fight so that the strongest gets to decide? Do you use leverage so that the cleverest gets to decide? Do you flip a coin? How do you feel about the Chevy F-150? The group doesn’t know. How do they feel about the Porsche? The group doesn’t know. How does either of you feel about the Tesla, or the Rolls-Royce, or the Lexus? The group simply doesn’t have enough information to find your group’s MO.

To find the MO, all members of the group must share their internal dialogues. Which cars did members like best and least, and how did all the others compare? As your internal dialogue combines with everyone else’s, your group will come to understand which car the group desires the most, the MO.

To allow members of the group to compare their levels of desire consistently, we impose a scale, a measurement. In the same way that we use inches or centimeters to compare how tall each of us is, we can use a finite scale to measure each individual’s amount of desire. The option(s) you desire least get the lowest number on the scale, say “0.” The option(s) you desire most get the highest number on the scale, say “9.”

After both of you do that, we find the average score (total score / 2 people) of each choice.

Now we see clearly that the group’s MO is the Tesla, the car with the highest average score. It doesn’t matter that the car was no one’s top choice, just like, when you did your internal dialogue it didn’t matter whether or not your final choice had either the design, power, gas mileage or reliability you desired most. You most desired the car with the best combination. The highest average for the group constitutes the best combination for the group, and the most desired option(s).

Note that you didn’t have to choose one car and then try to convince, beat, bribe, gerrymander, threaten, misrepresent with fake-news, or trick the other person into agreeing with you. You didn’t have to do anything except tell the group what you wanted.

Note also that you could have been less than honest and given all other cars besides the Porsche a rating of “0.” If you had, you and the other person would have flipped a coin between the Porsche and the Chevy F-150. You could either have a 50-50 chance of getting something you hate or something you love, or a 100% chance of getting something you thought was really good. The system only knows what you tell it, and if you tell it something less than honest, its answer will be likewise skewed from the best answer for the group.

Finally, note that the MO is not static. Since the MO exists for a certain group at a certain time, if a single person leaves the group, the MO changes. If someone else joins, the MO changes. If we calculate the MO today and then calculate it again tomorrow, the MO changes, because, as time passes, we have new ideas, change opinions, and new things happen.

Is it impossible to think that a voting method could, every time, identify a group’s most desired candidate if it allowed all voters to score a finite set of candidates on a set range and then define the winner as the candidate with the highest average of those scores, the MO?

“But doesn’t our current election identify the most desired candidate already?”

Consider what our elections do; elect the candidate with the largest group. First candidates identify their political platforms, where they stand on the issues. Then we all pick one candidate to support, like picking one car. And then we fight each other to make our group of supporters the largest group so that our candidate wins. Just like in the car example, the voters don’t know how anyone feels about all the candidates. Of course, it doesn’t matter if there are only two candidates, but once we have three or four or five, it matters a great deal. If we don’t ask the right question, we don’t get the right answer.

“But doesn’t ranked-choice voting (RCV) ensure ‘majority rule’ because it requires a candidate to have a group that constitutes over 50% of the vote?”

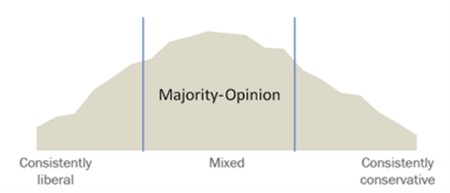

Consider a public opinion curve, one that plots along the political spectrum from “no-never” to “yes-always” the number of people who agree with political positions. You can visit Pew Research Center (https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/interactives/political-polarization-1994-2017/) to see more examples of these curves.

In any curve, there is one mathematical center, the MO.

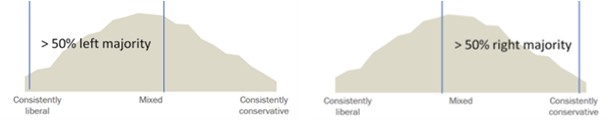

However, the curve can be cut up in any number of ways such that one piece contains > 50% majority of the voters’ opinions, a numerical majority. Which of these numerical majorities is supposed to be the right numerical majority for the population? The strongest one? The most cunning? The most well-financed? The most devious? How do we know if any represent the MO without first calculating the MO?

RCV identifies a numerical majority, but is it the MO? We can never understand how much each voter desired each candidate and never combined those desire-scores to create the MO in the first place. RCV works like plurality voting. It divides us, again, into camps that must fight for supremacy. The difference is that RCV, if no candidate obtains a >50% majority, dissolves the least supported camp(s) and redistributes voters to new ones until it constructs a >50% numerical majority. And even if a >50% majority was obtained on the first “election run,” we still don’t know that majority’s relationship to the MO. We must always ask the people how much they desire all the options, and then use all of their answers to find the MO, and RCV doesn’t do that.

Also, RCV uses a method to construct a numerical majority, but why should it use that method? RCV could have dropped the candidate with the most lowest-rankings, and recalculated. And then repeat until it produced a candidate with a constructed 50% numerical majority. It would be a different winner, but still a winner with a constructed 50% numerical majority. Which method is then the “correct” method, and how does one make that determination?

Score voting methods, where every voter scores every candidate and the high score wins, identifies and elects the voters’ most desired candidate, every time. Score voting methods also give an obvious advantage to politicians who align their political platforms as close as possible to the MO. Voters aren’t forced into candidate camps, but rather have their full say on every candidate. And voters rate candidates independent of how they rated any other candidates; they can even give candidates the same score. When we are led by the MO, we are led by the people and not the candidate-camp that was most funded, best at gerrymandering, or most manipulative.

People right now are working to get you the MO. They are active in California, Oregon, Nevada, New Hampshire, Washington State, Texas, Colorado, and Florida, and more are joining this ground-swell every day. If you want the MO (and, by definition, I know you do), please reach out to these websites, because we won’t get the MO without trying to get the MO.

It’s time we demand MO, it’s time we get MO, it’s time for MO.

Score voting, it’s time.

Daniel Jones says

Thank you, Ted Getschman, For bringing Us this “MO” Idea and some explanation about it.

It seems to me, that to use this innovation for group decision and vote casting, in Our National and State Governance Systems is a good Idea,..if it allows Us Freedom from the Personality Parade Dog and Pony Shows and, instead, a chance to study and decide on the positions and policies, they advocate and offer Us.

Question: Could “MO” be used to study and rate the platforms of Individuals and Parties, on an item by item basis?

The final ballot could list the Candidate, so as to limit the tediousness and time consumption, of details but to qualify for that moment and action, a Citizen must present a document that declares the Voter’s Participation in the study and “MO” of the platform Ideas. (Along with a Citizen Qualification I.D.. A state I.D., or drivers license or federal passport,.should be good enough.)

Basically, I see “MO” as a good path for Citizen Participation in the Governance of Their Nation and State. I think I will “work it” into my own work for “Direct Democracy”. I have been somewhat stumped by just what criteria would be best in Our “Responsible Studies for Good Citizen Participation”. “MO” would be a good starting point, I Think. It helps Us to get a Better Idea of where We are at, about these matters.

Thank You again for your work and sharing, in this. I will send the url of this article to the new “People’s Party”, for their consideration. I think, also, to ‘Braver Angels”, “Rebel Wisdom” and “Noetic Nomads”.

Tedman Getschman says

Daniel,

Thank you for taking the time to respond.

I think the true value in MO is that it exists and influences the election whether people or politicians know exactly where it is or not. Pew Research Center creates these charts, but how accurate are they and how fast do they change? Can they be made for every county election, city election?

When a score voting method is used, the candidate closest to MO gains an advantage. But the true value is that the only way for the candidate to try to find where MO is to align their platform to it is by really listening to a large segment of their voters across their whole political spectrum. They will really need to listen to the voters whom they intend to represent.

Of course, a candidate’s platform isn’t all a voter judges a candidate on. But I think it will be enough of a factor to advantage a candidate who pays attention to it and hinder one who ignores it.

I have a draft book over at scorevoting.us that explores these ideas. Maybe some more inspiration for your “Direct Democracy” work.

I wish you all the best. TEWG