From ProPublica‘s Derek Kravitz:

It’s been more than two years since President Donald Trump, who rallied campaign supporters with calls to “drain the swamp” of lobbyists and their ilk, took office. But despite that campaign promise, Washington influence peddlers continue to move into and out of jobs in the federal

In his first 10 days in office, Trump signed an executive order that required all his political hires to sign a pledge. On its face, it’s straightforward and ironclad: When Trump officials leave government employment, they agree not to lobby the agencies they worked in for five years. They also can’t lobby anyone in the White House or political appointees across federal agencies for the duration of the Trump administration. And they can’t perform “lobbying activities,” or things that would help other lobbyists, including setting up meetings or providing background research. Violating the pledge exposes former officials to fines and extended or even permanent bans on lobbying.

But loopholes, some of them sizable, abound. At least 33 former Trump officials have found ways around the pledge. The most prominent is former Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, who resigned in December after a series of ethics investigations. He announced Wednesday that he is joining a lobbying firm, Turnberry Solutions, which was started in 2017 by several former Trump campaign aides. Asked whether Zinke will register as a lobbyist, Turnberry partner Jason Osborne said, “He will if he has a client that he wants to lobby for.”

Among the 33 former officials, at least 18 have recently registered as lobbyists. The rest work at firms in jobs that closely resemble federal lobbying. Almost all work on issues they oversaw or helped shape when they were in government. (Nearly 2,600 Trump officials signed the ethics pledge in 2017, according to the Office of Government Ethics. Twenty-five appointees did not sign the pledge. We used staffing lists compiled for ProPublica’s Trump Town, our exhaustive database of current political appointees, and found at least 350 people who have left the Trump administration. There are other former Trump officials who lobby at the state or local level.)

As we’ve reported before, some former officials are tiptoeing around the rules by engaging in “shadow lobbying,” which typically entails functions such as “strategic consulting” that don’t require registering as a lobbyist. Others obtained special waivers allowing them to go back to lobbying. In a few cases, they avoided signing the pledge altogether. Legislation aimed at closing some of the loopholes is contained in the Democratic-led ethics reform package, HR 1, the “For the People Act,” which had its first hearing in front of the House Judiciary Committee last month. (The same bill was proposed in the previous session of Congress, and the sponsors cited ProPublica’s reporting.)

Increasingly, both lobbyists and the firms that hire them are taking advantage of a loophole unique to the Trump ethics pledge: A clause that allows former political appointees to lobby on “any agency process for rulemaking, adjudication or licensing” despite the five-year lobbying ban. “Rulemaking” includes deregulation, a Trump administration priority. “Rulemaking is mostly what agencies do, and that’s what most lobbyists do. So that’s a pretty big carve-out,” said Virginia Canter, a former Obama administration ethics attorney who now works for the nonprofit Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington. Companies have taken notice.

(n) “Lobbying activities” has the same meaning as that term has in the Lobbying Disclosure Act, except that the term does not include communicating or appearing with regard to: a judicial proceeding; a criminal or civil law enforcement inquiry, investigation, or proceeding; or any agency process for rulemaking, adjudication, or licensing, as defined in and governed by the Administrative Procedure Act, as amended, 5 U.S.C. 551 et seq.

—An excerpt from the Trump ethics pledge

Of course, the lobbying-government revolving door isn’t new. The Obama administration hired dozens of previously registered lobbyists, and many officials returned to K Street firms afterward. The “Daschle loophole” is named after former Democratic Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle, who sidestepped lobbying laws after he left the Senate by becoming a “policy adviser.”

Such influencers, more numerous than registered lobbyists, are allowed to operate because they don’t meet the legal threshold requiring them to list themselves as lobbyists. By law, registration is required if a person spends 20 percent or more of his or her time lobbying. That leaves a lot of leeway, said Paul Miller, president of the National Institute for Lobbying & Ethics, an association for what it calls advocacy professionals. (“We’re just like you,” the organization’s website states.) Miller said he hears from people who do lobbying work, but haven’t registered, and “their phones are ringing off the hook.” Miller added, “It’s our No. 1 priority and concern.”

Ex-lobbyists play prominent roles in the Trump administration. The acting administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (and nominee for the permanent job), Andrew Wheeler, is a former coal industry lobbyist. David Bernhardt, the acting Interior Department secretary and nominee for the permanent position, was chair of a lobbying firm’s natural resources division.

By our count, at least 230 former and current registered lobbyists have worked in the Trump administration.

The departments of Commerce, Defense, Energy, Interior, Justice and Treasury, as well as the Office of Management and Budget, did not respond to questions about their former employees-turned-lobbyists. The Department of Homeland Security directed questions to the White House, which declined to comment. The departments of Health and Human Services and Housing and Urban Development noted that the ethics pledge doesn’t prohibit former Trump officials from lobbying Congress or career employees at the agency.

At least 18 former Trump officials have become registered lobbyists at the federal level. Typically, they have been careful to avoid violating the ethics pledge. That usually means they interact with representatives, senators and congressional staff, but not with appointees at federal agencies or the White House. Here are several who have gone into lobbying jobs in the past year:

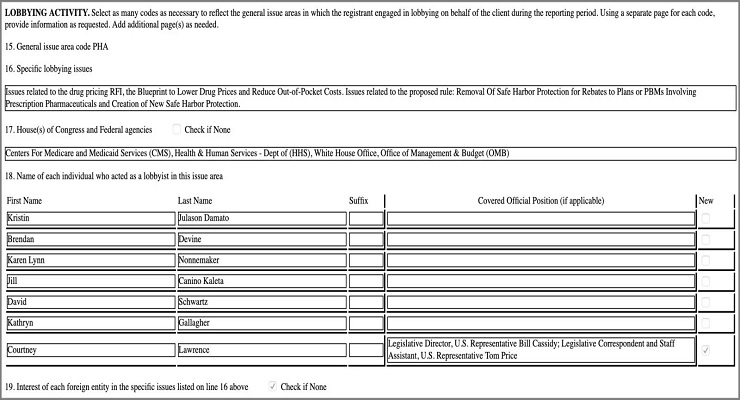

Courtney Lawrence was a longtime aide for Reps. Bill Cassidy and Tom Price and a federal lobbyist for the insurance trade association America’s Health Insurance Plans before taking a job as assistant secretary for legislative affairs at Health and Human Services in March 2017, when Price briefly headed the agency. Lawrence stayed for 18 months before leaving in August 2018 for a director role at Cigna Corp., the health insurance conglomerate.

Lawrence registered as a lobbyist with Cigna in October. Her disclosure forms state that she was working on proposed changes to Medicare, the Affordable Care Act and prescription drug rebates. Federal lobbying disclosures show that Lawrence was one of several lobbyists to communicate with federal agencies and the White House, and not just members of Congress. In a statement, Cigna asserted that the lobbying disclosure — which was prepared by the company — is inaccurate. Cigna blamed a “formatting issue.” The statement said Lawrence “does not and will not lobby the Executive Branch.” The company said it would correct her lobbying disclosure form.

A federal disclosure form filed by Cigna indicates, in the response to No. 17, that Courtney Lawrence lobbied the White House or federal agencies on behalf of the health insurance company. Company officials assert that Cigna filled the form out incorrectly. They blamed a “formatting issue.”

Jared Sawyer, a longtime Senate committee attorney and lobbyist, was deputy assistant secretary for financial institutions policy at the Treasury Department, overseeing two offices that regulate and monitor financial institutions and insurers. Sawyer was the lead policymaker on a set of proposed rule changes that would ensure that asset management and insurance firms don’t face the same regulations as banks.

Propublica has the full story.

Leave a Reply