Ranked-choice voting election results reveal little about voter desires. Consider this ranked-choice voting (RCV) election result in a race between four candidates. After the first round we have this:

- Candidate A: 60% of the vote,

- Candidate B: 40% of the vote,

- Candidate C: 0% of the vote,

- Candidate D: 0% of the vote.

RCV seeks to ensure that one candidate receives more than 50% of the vote. It would use a process of eliminating the least voted-for candidate to create such an outcome. In this election, where one candidate received 60%, RCV has no need to eliminate other candidates. This represents the purest version of a RCV result as it comes directly from the voters without any manipulation by the voting method.

Candidate A wins quite handily. Out of the 50 U.S. presidential elections that include a popular vote of the people, only four presidential candidates have won with such a substantial margin (Harding: 1920, Roosevelt: 1936, Johnson: 1964, Nixon: 1972). This suggests to us that we have implemented the Democratic principle of “majority rule.” Further, the winner appears to have a clear mandate from the people. Finally, we find ourselves wondering what caused the poor performance of Candidates C and D; clearly, we were not buying what they were selling. We can glean nothing further from the RCV result, but this appears to be sufficient for us to be happy about the Democratic nature of the result, even if we supported Candidate B.

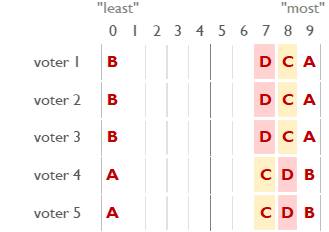

However, we fortuitously asked each voter to tell us how much they desired each candidate in relation to the others on a scale from 0 (“least”) to 9 (“most”). That information appears below:

Once we can see what each voter desired, the result of the election takes on a vastly different look. We did not elect the most desired candidate (C received an average level of voter desire of 7.6, D = 7.4, A = 5.4, B = 3.6). In fact, we elected the second least desired candidate. Further, the results of the election made it appear that the population was divided between the two candidates who turned out to be the least desired! What kind of mandate does the winner have? Did we not just unknowingly reinforce polarization and dysfunction in our society? The best outcome for RCV appears to have been one of the worst outcomes for the voters.

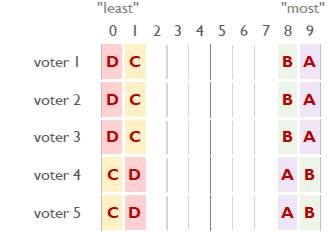

But you may ask, what if the voters really felt like this:

If this were the case, the RCV election would have shown the same result: A=60%, B=40%, and C and D = 0%. But now we know that the amount of desire the voters had for each candidate was: A = 8.6, B = 8.2, C = 0.6, and D = 0.4. Clearly, candidate A was the most desired candidate and in this case with B taking second. RCV did pick the best candidate, and this may have been the case. So, which was it? Did we elect one of our most desired candidates or one of our least desired candidates? Did our voting method give us one of the most divisive or one of the least divisive candidates? RCV identifies a winner, but why should one of the potentially least desired and most divisive candidates win? RCV leaves us only with the option to hope that things aren’t too bad.

Is it completely ridiculous to simply have each voter specify how much they desire each candidate and then have the voting method declare the voter’s most desired candidate the winner?

If RCV is not designed to identify the voter’s most desired candidate as the winner, what was it designed to do? And who designed it to do that?

Discover more:

Leave a Reply