States’ winner-take-all allocation of presidential electors dates back to the early 1800s, but in our era, it seems to be having an increasingly perverse effect. The Framers would have been disturbed by two consequences: excess power in 10–12 “swing states”, and voter apathy in the remaining “safe states”.

The swing states attract not only additional campaign attention but political pork and other influence. In the safe states, voters consider their votes devalued because they are unlikely to make a difference, so they are less likely to turn out. This affects the down-ballot elections. The Framers were familiar with a third problem in the Electoral College itself: its voting method, choose-one Plurality Voting (COPV), is highly vulnerable to vote-splitting, and thus can fail in elections with more than two candidates. As specified in the Twelfth Amendment the Electoral College votes only once—in the absence of a majority, the decision moves to the House of Representatives.

The swing states attract not only additional campaign attention but political pork and other influence. In the safe states, voters consider their votes devalued because they are unlikely to make a difference, so they are less likely to turn out. This affects the down-ballot elections. The Framers were familiar with a third problem in the Electoral College itself: its voting method, choose-one Plurality Voting (COPV), is highly vulnerable to vote-splitting, and thus can fail in elections with more than two candidates. As specified in the Twelfth Amendment the Electoral College votes only once—in the absence of a majority, the decision moves to the House of Representatives.

The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC) is a way to solve all three of these problems. States joining the compact agree to allocate their electors to the candidate who wins the popular vote among the NPVIC member states. Every vote would matter, even if a voter were a party’s only supporter in a state. By reducing the Electoral College to a formality, the NPVIC would mitigate its flawed voting method.

These problems may have other solutions, possibly simpler. For example:

1. A simpler interstate compact to allocate electors based on district results, like Maine and Nebraska already do, or simply proportionally. While the former approach would not completely eliminate the swing-safe problem, pushing it down to the district level might diffuse it, and it would not require cross-state vote tallying.

2. An alternative voting method, less vulnerable to vote-splitting, would enable additional parties, offer voters more choices, and reduce their apathy, probably far more than would modestly increased influence in the quadrennial presidential election.

3. An alternative voting method in the Electoral College would enable it to handle multi-party elections with less concern for vote splitting. An example of this is a papal conclave of the

College of Cardinals, which votes with a majority requirement and an unlimited number of rounds. However, this would require a Constitutional amendment, on top of the Twelfth.

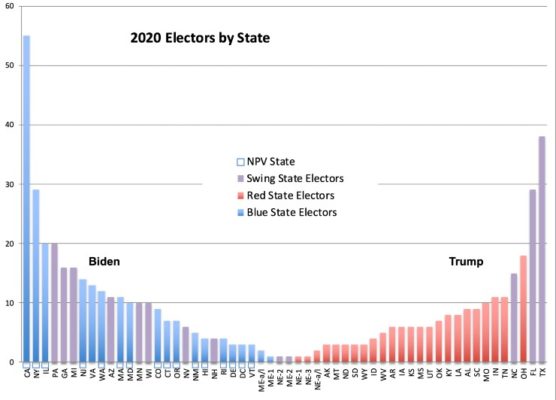

But the NPVIC train has already left the station. As of the end of 2020, 15 states plus DC have jumped on, with 196 of the 270 electors needed for the compact to be activated. The NPVIC was launched in the wake of the 2000 election by disgruntled Democrats, but Republicans increasingly see its potential for reducing political pork. What should be done now?

NPVIC’s Flaw

The NPVIC was unfortunately written assuming the current COPV method, with no regard for alternative voting methods. The compact text says that the chief election official of each member state shall:

1. “determine the number of votes for each presidential slate”

2. “add such votes together to produce a ‘national popular vote total’ for each presidential slate”

3. “designate the presidential slate with the largest national popular vote total as the ‘national popular vote winner’”

Not all voting methods produce “a number of votes”. In fact, most do not. Neither the rating nor ranking methods work that way. The various methods produce various numbers, but they are apples and oranges. Tossing them all in a blender might produce an interesting smoothie, but not a useful count. But perhaps there is a way to combine different voting methods’ tallies or ballots that is not only meaningful but unobjectionable?

Not all voting methods produce “a number of votes”. In fact, most do not. Neither the rating nor ranking methods work that way. The various methods produce various numbers, but they are apples and oranges. Tossing them all in a blender might produce an interesting smoothie, but not a useful count. But perhaps there is a way to combine different voting methods’ tallies or ballots that is not only meaningful but unobjectionable?

Any new counting rules for combining tallies from different voting methods should be:

1. simple: minimal and understandable

2. accurate: not reduce the accuracy of the election results

from those of the incumbent method

3. fair: not disadvantage any voter group

Two common tally formats and rulesets

Counting rules would transform the tallies or ballots from disparate voting methods into a common tally format. Obvious candidates for this format would be the minimal version of Score Voting (SV) known as Approval Voting (AV), or something resembling the incumbent voting method, COPV. The first is an evaluative (rating) method, the second an allocative (sometimes called cumulative) method.

Both AV and COPV ballots assign candidates 0 or 1, but under AV the candidates are rated independently, while under COPV a ballot is a discrete token that can belong to only one candidate. Under COPV there is a fixed ‘amount’ of the vote to be allocated: each of the V voters has only one ballot to allocate to one candidate.

1. An AV-based common tally format would scale the maximum tally per candidate to V. The total would be less than V*C, where C is the number of candidates, but would probably be greater than V.

2. A COPV-based common tally format would limit the total amount of vote to V. The total might be less if some candidates’ votes got “lost” (e.g., they failed to reach some minimum threshold).

AV is probably the way to go, given COPV’s infamous vote-splitting problems. This is indeed proposed in Dr. Warren Smith’s article about NPVIC problems and solutions.

Smith suggests counting rules to combine tallies from five different voting methods, and the common tally format is a rating scaled to AV’s parameters. Combining COPV and AV tallies is simple: just add them. SV tallies must first be scaled, a simple matter. The ranked methods (Instant Runoff Voting and Condorcet methods) require substantially more calculations but can be massaged into providing summable numbers for multiple candidates.

How about a COPV-based format, which should limit the total number of votes to V? To convert SV or AV, maybe one could scale the results by 1/(C*R), where C is the number of candidates and R is the rating scale. Converting the ranked methods here is much easier: take Smith’s rule for the top two candidates (Winner and Second), and ignore the rest.

Assessing the two counting rulesets against the three criteria

How would these counting rulesets satisfy the three criteria of simplicity, accuracy, and fairness? They are generally simple, at least no more complex than the ranked methods are already. I cannot provide a mathematical treatment, but it seems obvious that both would be more accurate than the incumbent COPV alone. Clearly, Smith’s AV-based ruleset is the more accurate of the two. It “counts all the votes”.

But how about fairness? Under option two, ranked methods’ tallies would be truncated to just the top two winners, leaving weak third parties ignored and irrelevant, but making strong third

parties a winner-take-all threat for second place. This might encourage a state’s strongest party to surreptitiously support a third party, as the Republicans promoted Ralph Nader in 2000. These two vote-splitting weaknesses would negate two of the goals of voting reformers’: increasing choice in candidates and reducing the swing-state effect.

Another fairness issue is the influence of one state’s system on voter behavior in another state. In all voting methods, voter choices are influenced by an expectation of what other voters will do. This is particularly true of COPV because it is so vulnerable to vote-splitting (e.g., spoilers and the wasted-vote dilemma). COPV compels voters to choose from the Schelling set—the “electable” candidates on whom like-minded voters would coordinate in the absence of communication. COPV or a ranked method with a truncating counting rule (e.g., just the top two candidates) in one state might cause voters in other states with poor voting methods to abandon favored but weak candidates, or fear of wasting their vote.

On the other hand, the existence of better voting methods in other states may expand the Schelling set, making the choice less obvious for voters in a COPV state. Would they be harmed, e.g., tempted into splitting their votes? Perhaps—despite voters having polling data showing a race to be close, vote splitting still happens occasionally in US presidential elections, most infamously in 2000. But the solution here is better voting methods, not rejecting the NPVIC.

Conclusion

I can endorse the NPVIC with Smith’s proposed counting ruleset, assuming that others find it as obvious and unobjectionable as I do. The Electoral College is fundamentally incompatible with multi-party democracy. Even if states allocated their electors proportionally to candidates’ state-level election results, and even if the Electoral College used a decent voting method, each elector would still represent only one candidate.

Even if we voters used the best possible voting method, in a multi-party system the Electoral College step would muck things up. Without a Constitutional fix, the only solution is an interstate compact to decide the winner before the Electoral College, and then assign all electors to that winner. Today we are far from having a multi-party system, but to prevent more vote splitting like in 2000 we need the NPVIC.

However, we should not let the NPVIC tail wag the voting-reform dog. The presidency and vice-presidency are merely one (important) pair out of some 500K elected offices. What we need even more than the NPVIC is a sensible voting method, one that is much less vulnerable to vote splitting. Fortunately, it seems that the NPVIC is probably compatible with at least some alternative voting methods, most obviously Approval Voting.

Leave a Reply