In an ever increasing globalized world marred by uncertainty and countless threats, relations between Britain and Zimbabwe are at an opportune moment to define what diplomacy and international relations should look like between two countries especially considering the colonial history of the two countries. After almost two decades of stalemate, evident change has come to Zimbabwe. British Prime Minister Theresa May now has found a credible ally, in new Zimbabwe President Emmerson Mnangagwa, to work to rebuild trust with former its colonial master. A closer feeling of union between the two nations can only serve to promote peace in the region and worldwide.

Relations between Harare and London became frosty in 1997 when the Labor government led by Mr. Tony Blair refused to honor obligations entered into with the Margaret Thatcher Conservative government who had committed to fund land reforms in Zimbabwe. The standoff was further compounded in early 2000 when the accelerated land reform program begun and accusations by former president Robert Mugabe that Britain was funding the opposition parties in Zimbabwe. This led to the government introducing the Political Parties Act of 2001 that barred foreign funding for political parties.

The re-engagement drive has intensified in recent months with Zimbabwe’s Foreign Affairs and International Trade Minister, Retired Lieutenant-General Sibusiso Moyo (the man who appeared last November on television announcing the coup), having visited London at the invitation of British Secretary of State Boris Johnson during the Commonwealth Heads of States and Government meeting last month. Zimbabwe’s main opposition and presidential candidate for the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) Alliance Advocate Nelson Chamisa was in London this week where he also held a meeting with Boris Johnson focusing on Britain-Zimbabwe relations ahead of harmonized elections in July/August in Zimbabwe.

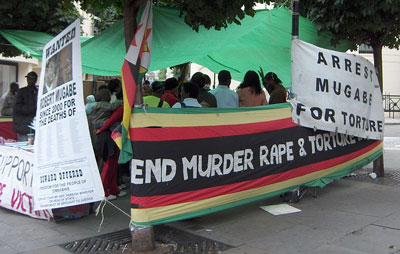

The vocal criticism of human rights abuses and violations that led to the so called “ethical foreign policy” seem to be slowly becoming history although Britain and allies still insist that full diplomatic channels will only be opened if the harmonized elections are declared free, fair and credible.

Following this improved start, the long-overdue idea of British-Zimbabwe diplomacy should be formulated and unleashed as a tool of foreign policy globally. As alluded to above, the early 2000 accelerated land reform issue is at the center of the quarrel between the two nations. However, despite this quarrel which Britain internationalized and eventually led to the enactment of the Zimbabwe Democracy and Economic Recovery Act of 2001 by the United States Congress which imposed economic sanctions on Zimbabwe that need to be reviewed annually by the US president who can then choose to extend the sanctions by another year or completely remove them. Although geographically apart, the two countries historically maintain longstanding trade and cultural links.

As of this day and forward, Harare and London should design an ethical foreign policy that mutually benefits both states beyond the upcoming general elections in Zimbabwe. As globalization takes hold, cooperation and alliance amongst states is no longer a matter of choice, but is an absolute necessity for nation-states to develop and offer better living standards for their citizens.

In recent decades, however, Zimbabwe has seen an explosion in population growth with a younger population making about 65 percent of the total population demanding jobs and economic uplift from their governments. To effectively address those needs Zimbabwe has no other viable option than vying for trade and business linkages with their counterparts like Britain, attracting foreign direct investment inflows into Zimbabwe; but also collaborating on security concerns and tackling the increased complexity of our era brought about by technology among other factors.

Britain and Zimbabwe could offer a start, in softening such inter-linkages via Britain-Zimbabwe politico-economic and monetary collaboration immediately after the national elections. On the diplomatic front, there is an old adage that state that there is strength in alliances and Britain-Zimbabwe diplomacy could soon be a force to be reckon with in African and international diplomacy. The multidimensional and complexities of issues facing Zimbabwe can no longer be solved by internal actions alone. For states to succeed and prosper in this environment rather requires multilateral solutions, partnerships and alliances to confront those challenges and Zimbabwe is not an exception.

David Anderson says

Good article, Farai, v. informative.

I’d never heard of our US 2000 Act in response to Z.’s gvt policies.

Now is a good time for Z -UK rapprochement given the UK is nearly out of friends with Brexit.

Keep the articles coming.

David Anderson

NYC

Farai Chirimumimba says

@David, many thanks