The unending conflict in the Central African Republic has enjoyed a set of explanations. Several sources point to France’s involvement in the CAR as one of the principal reasons why the CAR is dysfunctional today. Dysfunctionalism appears to be a good explanation of the conflict in that country. Structural issues have also been tagged as causal mechanisms for the conflict in the CAR.

Beyond these structural factors, the CAR’s conflict has also been explained from the perspective of complex regional and international dynamics. Chad has been found to meddle in the politics of Chad in the last 20 years or so. The CAR’s conflict does not also escape the greed and grievance arguments and non-compliance with democracy appears to be a plausible perspective to understand the successful coups in that country since 1991.

However, beyond these widely accepted perspectives on the root causes of the conflict in the CAR, the failure of peacebuilding in the CAR is also to blame for the unending conflict in that country. Between 1959 and 1993 France was the sole “peace-broker” in the CAR. However, peace was on its terms.

Central African Republic history

After nominal independence from France, David Dacko (President of the First Central African Republic, CAR, from independence on 13 August 1960 until 31 December 1965 and of the Second Republic 21 September 1979 to 1 September 1981), Jean-Bédel Bokassa (ruler of the CAR from 01 January 1966 till 20 September 1979) and André Kolingba were successful coup perpetrators during the Cold War period in the CAR. But the (re)democratization of the 1990s occurred when André Kolingba was in power.

Faced with this situation Kolingba was obliged to accept multi-party politics which he had abolished in 1986, as did David Dacko in 1962. The 1991 constitution reinstated multi-party elections as the only authorised means of peaceful transfer of power in the CAR. Elections were held in 1993 and Ange Félix Patassé was voted-in as President of the Republic in democratic elections in which Kolingba, a former coup plotter in a democratic dispensation took part.

On 15 March 2003 former Army Chief, General François Bozizé Yangouvonda ousted Patassé from power through a coup d’Etat. He was elected in multi-party elections in 2005 and 2011. Thereafter, he too would be removed from power through force on 24 March 2013 by Michel Am-Nondokro Djotodia at the head of a rebel coalition dubbed “Seleka”.

Djotodia’s rebellion led to ethno-religious violence between his incidentally Muslim Seleka and the ‘Christian’ Anti-Balaka group, thus forcing him out of his self-declared Presidency in favour of Transitional President Catherine Samba Panza. Panza handed power to the democratically elected Faustin Archange Touadera in March 2016.

Dacko I became President of Government business at independence by seizing power in a coup in which he used a squadron of pygmies armed with poisoned arrows to surround Parliament. The French turned a blind eye to this coup.

The French equally endorsed Bokassa’s coup that overthrew Dacko I and then later on overthrew Bokassa to install Dacko II once Bokassa became a nuisance. And French security operatives assisted Kolingba in his 1981 coup d’état. France ignited its “Paristroika” in the early 1990s and appeared to accommodate Patassé’s win in the 1993 democratic elections even though Patassé was not a very good friend of the French.

The conditions for chaos in the CAR had been further laid down by Kolingba during his time as a military dictator. Patassé failed to handle the conflict appropriately and management of security in the CAR became total anomie in the Patassé years.

France and its allies in the CEMAC seized the opportunity to create the Inter-African Mission Monitoring the Bangui Agreements (MISAB), then came the United Nations Mission for the Central African Republic (MINURCA) and finally France returned to the CAR through its regional puppet States of the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC) notably Chad in the form of the Multinational Force in the Central African Republic (FOMUC).

All these peace-keeping forces failed to prevent the resurgence of conflict and the FOMUC even functioned as a ploy to root out Patassé when Bozizé took power. Bozizé’s chaotic rule was the accompanied by additional peace initiative frameworks that kept on failing to address the root causes of the problem. In effect, the Bozizé years witnessed a number of peace-keeping missions:

- Central African Republic Peacebuilding Mission (MICOPAX) that replaced FOMUC on 12 July 2008

- United Nations Mission in Central African Republic and Chad (MINURCAT) with its bridging mission being known as the European Union Force (EUFOR) Chad/CAR

- Integrated Peacebuilding Office in the Central African Republic (BINUCA) replacing MINURCAT at the end of 2010 and also created to continue to work for the benefit of the CAR.

BINUCA absorbed the United Nations Observation Office in the Central African Republic (BONUCA) and other UN missions in CAR. BONUCA had been created to stay in the CAR after the MINURCA completed its mission in April 1998.

Following the March 2013 coup d’état by the Seleka, the African Union’s Peace and Security Council (PSC) set up MISCA. The MISCA mission was complimented by a return of 2000 French troops to the CAR under Operation Sangaris and by an EU force that sent its first troops to CAR in April 2014 with total troop strength reaching 800.

The United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA), a UN peacekeeping mission, then replaced MISCA in April 2014. Its mandate was to protect civilians under Chapter VII of the UN Charter. It had over 10,000 troops on the ground with a mandate that included:

- Support for the transition process;

- Facilitating humanitarian assistance;

- Promotion and protection of human rights;

- Support for justice and the rule of law;

- Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR);

- Repatriation processes.

What is the goal in the Central African Republic?

Despite all these peace initiatives peace in the CAR remains fragile and conflict has continued. The CAR has also had its share of transitional arrangements, and various liberal peace-initiatives (LPIs) such as elections and national dialogues. Attempts have also been made, especially since the Seleka vs anti-balaka tit-for-tat, to build frameworks in which CAR citizens can discuss the issues facing their country, yet conflict persists.

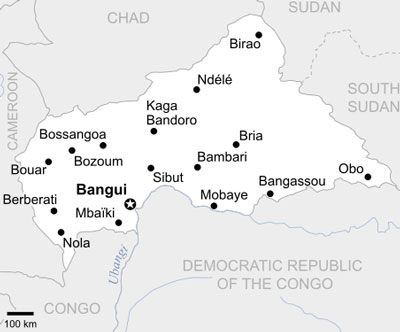

In spite of the election of Touadera, a big chunk of the CAR territory, especially in its northern regions, is still in conflict. The country is currently repartitioned de facto between armed groups. The unending conflict in the CAR has destroyed its economy and has kept its the citizens in poverty and misery despite very vast natural resources and a great human capital potential.

What the literature tells us is that the various conflict resolution initiatives in the CAR failed because they did not target the root causes of the problem. Indeed, they did not. The focus has been on peacekeeping and peace-making and the usual LPI such as elections, state and institution building. These frameworks have been replicated with the same results. One can then deduce that the conflict persists because of the repeated use of these frameworks.

This begs the question of why has there been a repeated use of these frameworks knowing fully well that they will produce the same result in terms of failure to address the root causes of the conflict. One begins to think that the agenda behind conflict resolution is the real reason why the conflict has persisted. There seems to be no real intention to end this conflict. Even the African Union is playing at this game, to the extent of rolling back peace-keeping to peace-enforcement. So who is benefitting from chaos in the CAR?

It is an open secret that France is still the colonial master of its former colonies. It has never wished for its former colonies to be independent as it totally relies on their resources to remain relevant in the concert of world powers. Its preferred method to control the resources of francophone States is not hidden. France remains committed its colonial past.

Good governance, democracy and accountability of the Governments of its former colonies are anathema to France. Why? It is because a loss of its colonial sphere would mean that huge chunks of money from colonial resources and reserves would go to the people of these countries and not to the French treasury.

Stability in these countries would mean economic growth and the empowerment of a middle-class that would assert its independence. Therefore, France that continues to play a major role in the peace-building initiatives in its unstable ‘former colonies’ such as the CAR stands as the symbol of an agenda that appears to be endlessly replicating inadequate peace building frameworks.

There is therefore an urgent need to rethink peacebuilding in the CAR. The solution must start with stopping French involvement in the CAR. Regional neighbours equally have an alibi as seen in the FOMUC. The African Union has to take up its responsibilities and redesign the peacebuilding approach in the CAR, bringing in frameworks that will normalise relations between its citizens.

It would not be too bold to say that the Central African Republic needs a transitional arrangement in which it can be administered from the AU. But will the AU rely on the EU or China for money to do this? Also, will it have to be the current AU that is so internally challenged? Is Africa stuck between a rock and a hard place? The future looks bleak under the current leadership that is outright criminal in several cases and has blatantly failed. A new peace-building agenda is needed, but a new set of thinkers and leaders is equally needed to drive this agenda, one composed of objective, honest and patriotic Africans.

David Anderson says

EXCELLENT article to keep us up to speed on this little known catastrophe, Ngah.

I notice your usual strong criticism of France: keep up the good work! They’re a terrible influence in most places in their supposed empire and the point you make about good governance in their colonies being an anathema to them is spot on.

I’d also include the Christian-Muslim divide as a problem which it seems (only in the past few years though I could be wrong) has widened significantly.

David Anderson, NYC