The unanimous decision, Friday 24 August 2018 by the Constitutional Court of Zimbabwe (ConCourt) to uphold Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) candidate Emmerson Mnangagwa’s victory in the 30 July 2018 presidential election challenged by leading contender, Nelson Chamisa of the Movement of Democratic Change (MDC) Alliance, has raised one major question: ‘was the court partisan’?

This article argues that the court was correct in hearing the application but that the resulting decision was flawed and inconsistent, as it failed to uphold voter’s rights and chose to ignore evidence, thus making the court’s decision appear partisan. This situation has potentially serious and adverse implications for judicial legitimacy and democracy in Zimbabwe if the ConCourt continues to issue rulings this way.

Background

The general elections of 30 July 2018 were the first post-coup elections and marked a turning point in the country’s political history. “The results were announced early Friday 03 August 2018. Mnangagwa won 50.8 percent of the vote, ahead of Nelson Chamisa [who had]…44.3 percent, the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC) said.”

“[Chamisa] had brought the legal challenge saying the vote was marred by “mammoth theft and fraud“”. “Chamisa claim[ed] that he garnered 60 percent of the votes cast and Mnangagwa had less than the required 50 plus one vote…”

The ConCourt’s decision

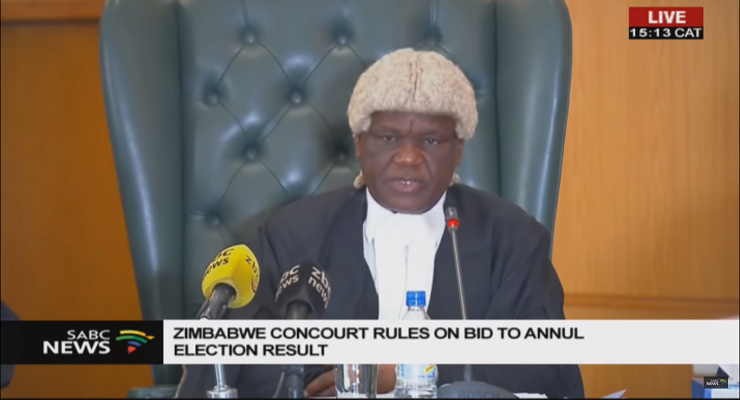

“Zimbabwe’s constitutional court [of nine Magistrates] on Friday [24 August 2018] unanimously upheld …Mnangagwa’s narrow victory.” Chief Justice Luke Malaba dismissed Chamisa’s court application saying: “It is not for the court to decide elections; it is the people.” Justice Malaba said Chamisa has failed to adduce “clear, direct, sufficient and credible” evidence.

Malaba instead praised the ZEC for producing “clear and tangible” evidence against Chamisa’s allegations. ZEC proved through the V11 forms that allegations of unpopular forms were false, he said.

While the whole bench correctly argued that: “Applicant (Nelson Chamisa) needed more evidence than the mere admission by ZEC of the inaccuracy of the figures,” its final decision to dismiss the election petition without due regards to rigging is a blow to electoral justice as the court has instead taken sides with those who rig elections.

The ConCourt’s decision and voter rights

There was a 40,000 variance between the presidential election ballot cast and parliamentary election which ZEC failed to explain and also failed to provide the PE2005/AA forms for those who would have refused ballot paper for any reason as required by law. The ConCourt chose to ignore this grave issue.

Thus, the court’s position no doubt did immeasurable damage to equal protection rights the court claimed to be guarding since it favored a timely tabulation of ballots over an accurate recording of the vote.

ConCourt ignores evidence, shows signs of partisanship

The biggest criticism of the ConCourt is probably its emphasis on wanting primary data in the form of residual ballots as evidence of substance. Malaba said: “Chamisa should have based his case on “ballot box evidence”. He adds “no such proof was adduced.”

I argue that the ConCourt had no business lecturing the applicant (Nelson Chamisa) on what evidence to bring or not to bring to court. It should have just restricted itself to whether the evidence availed by the applicant was of substance to warrant setting aside of the result and ordering a re-run of the presidential election.

By issuing such a ruling in this case, the ConCourt exposed itself to more charges of blatant partisanship since its decision can be seen as a thinly-veiled maneuver by the rather conservative bench to hand victory to a junta installed Mnangagwa in fear of repercussions since coup leader Retired General and now Vice-President Constantino Chiwenga had on the eve of the ruling said “nothing will change…”

Absence of dissent

Whether or not this is accurate, there is an inescapable irony in the Court’s unanimous decision that failed to garner a dissent, a rare occasion in Zimbabwe’s ConCourt but a reality in other jurisdictions like Kenya, the United States and Zambia.

A dissent could have argued that the ConCourt had exceeded its jurisdiction and infringed on the applicant’s rights through being unnecessarily demanding and would have added value to legal debates as was the case when current Chief Justice Luke Malaba and Justice Patel dissented in minority in the Mawarire v. Mugabe case in 2013.

Conclusion

The ConCourt’s unanimous decision of 9-0 on the July 30 presidential election in favour of Mnangagwa should go down in history as one of the court’s most ill-conceived judgments. In issuing its poorly reasoned ruling that gave the presidency to Mnangagwa, the whole bench of nine Justices unnecessarily exposed itself to charges of partisanship and risked undermining the ConCourts’ stature as independent, impartial arbiter of law.

If the ConCourt is to improve on its legitimacy in the eyes of the public, it must do a better job of making clear that it is an independent and non-partisan arbiter of the law. The attitude is that the status of the ConCourt will survive the Chamisa versus Mnangagwa dispute, as it has after other controversial rulings that include denying Diaspora vote. However, if the ConCourt continues to be partisan and use such questionable logic in its decisions, it risk losing relevance, casting doubt on the role of the entire legal system the ConCourt represents in Zimbabwe.

Leave a Reply