Africa has made remarkable democratic achievements since the early 1990s following a wave of ferocious internal conflicts in Mozambique, Rwanda, Burundi, Chad, Sierra Leone, Liberia and Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) to mention but a few.

In order for this progress to be sustained, Africa requires viable political parties, which play a key role in building and strengthening democracy. As a result, countries like Lesotho, Gabon, South Africa, Germany, United Kingdom and Zimbabwe among many others provide some form of public funding to political parties with representation in parliament (Masunungure, 2006).

In many democracies, public and private financing is the viable source of funding coming as either direct or indirect to political parties (Austin and Tjernström, 2003).

Literature review shows that the nature of political party funding may be broadly categorized as from: (a) payment of membership dues; (b) special financial contributions (c) donations by party executives, ordinary members and non-members; (d) sale of party souvenir, (iv) grants from government and organizations, (e) investment income and (f) finances by rich individuals and loans.

However, even though public funding was introduced to curb corruption, the abuse of public funds and the secrecy around private funding sources ignited a hotly contested debate locally and internationally on the current political parties financing models. Similarly, the main form of party financing, traditionally through membership fees, is no longer viable for the ever expanding role of most parties in modern democracies. This has forced political parties to seek private means of financing other than through membership fees, either from within or outside the party, which have been area subject of controversy in some cases especially with donations:

“That runs the risk of establishing inappropriate links between donating money and specific political decisions. In this context, the mere impression of misuse may in itself be sufficient to erode public confidence in the political system and its political actors and may thereby undermine the legitimacy of democracy” (Biezen, 2003).

Other challenges to political party finance as noted by Bryan and Baer (2005) include:

- Poor party fund management is pervasive arising from weak organizational structures and lack of transparency within parties.

- Politicians are often under pressure to facilitate the business interests of wealthy supporters, rather than the common good. This undermines citizen participation in the democratic process and the legitimacy of political parties.

- Candidates who are geared towards reform of the system are often squeezed out during the electoral campaign due to the high financial cost of running for office.

- Legal and regulatory reforms to address corruption in political party financing need to be adequately enforced. This includes the enactment of legislation, as well as additional resources to ensure compliance.

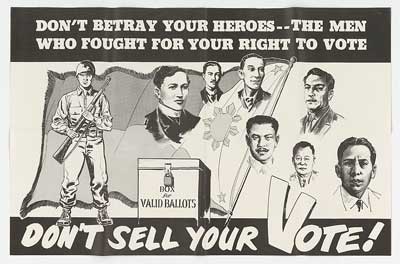

- Despite international concern, instances of voter-buying are not as pervasive in practice. Vote-buying constitutes the smallest part of party and candidate expenditure.

Ingrid van Biezen, (n.d) in a research paper titled: “Campaign and party finance” argue that:

“The pervasiveness of political finance scandals means that this constitutes a very real problem for contemporary democracies, with evidence suggesting that it undermines the legitimacy of political parties, politicians and potentially the democratic process itself: as parties and politicians are increasingly seen as office seekers driven primarily by their material self‐ interests, and are regarded by the public as highly susceptible to corruption, they have become the least trusted among democratic institutions and actors.” (e.g. Dalton and Weldon 2005)

Political party financing scandals that have rocked many states have resulted in calls for political parties to strengthen their governance and improve on transparency in managing of funds (Beizen. n.d).

In an article titled: “It took a scandal to get real campaign finance reform”, Zelizer, reminisced on the Watergate campaign finance scandal that brought down President Richard Nixon in the 1970s. Disclosure laws that followed produced a much more transparent process that allows voters and reporters to easily find out about where money is coming from and how much is being spent. Effectively they were designed to make sure that America will not entertain another Watergate.

Elsewhere the Jamaica Observer in an article titled: “PNP scandal gives urgency to campaign financing reform” , reported that senior members of the People’s National Party (PNP) of Jamaica has being accused diverted donor funds for personal use. An accusation that the party strongly denied has an unwarranted attack on the reputation of the party.

In South Africa, 2014 the ruling party Africa National Congress ( ANC’s) investment company Chancellor House relation with Hitachi Power Africa was subject of public scrutiny after Hitachi Power Africa deal won contracts worth R38.5bn from Eskom (national electricity company) to install boilers at the Medupi and Kusile coal-fired power stations. Commentators were accusing the ANC of making hundreds of millions by selling electricity to its voters over a five-year period. After months of public outrage, the ANC eventually sold its share in Hitachi Power Africa (EISA South Africa updates, 2014).

In 2016 Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak was cleared by the Attorney General after having been accused of allowing hundreds of millions of dollars meant for his party United Malays National Organization (Umno), to be put into his personal bank account. Although the case was cleared there are still questions being raised because of different versions of how the funds were donated (Bristow, 2016).

Joseph Balise, in an article titled: “Who is funding political parties, and for what benefit?” (Sunday Standard.info) asked the question, who financed Botswana’s 2014 general elections? This is because of the mystery surrounding political party financing in this southern African country. He alludes to the efforts that the opposition parties are making in lobbing for a legislated political funding. The opposition believes that the ruling Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) is abusing public resources for its benefit.

The practice of requesting state owned enterprises to dinners by the ruling party where they buy tables for thousands of dollars as the case in Zimbabwe is another case were the electorate should demand transparency. Vice-President Pelekezela Mpoko during a dinner to raise money for the 2016 Zanu-pf annual conference was quoted as saying, “blue-chip companies that are performing well are not willing to help the party in its activities yet they are the direct beneficiaries of its policies”(Mashaya, 2016).

All these cases and many others show that those who lead, or aspires to lead our must be measured by the guiding principles of integrity, morality, and the rule of law. All political parties are governed by the code of ethics attached to their internal constitutions, and it should be apparent to the leaders of the party that the internal constitution is backed by the rule of law, and that any allegation of fraud, attempted fraud, or theft of funds must be dealt with expeditiously in terms of law.

The very fact that the political parties accept funds from people who are not members opens them up to public scrutiny, as those donors will have more than a passing interest in the affairs of the organizations that have benefited from their generosity.

As a result, many regional bodies and non‐governmental organizations are now focused on investigating the funding procedures of political parties and election campaigns, and come up with strategies that improve internal democracy and financial management that can reduce corrupt tendencies. Organizations taking an active role include the African Union (AU), the South African Development Community (SADC), the Council of Europe (CoE), the Organization of American States (OAS), the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA), Transparency International (TI), and the World Bank. The problems of party finance is affecting both developed and less developed nations (Biezen. n.d ).

For example Transparency International Denmark released the first ever anti-corruption study of Denmark’s institutions which highlighted secrecy in the funding of political parties and legislative candidates as the country’s biggest potential corruption issue. In the report further reviewed that corruption tendencies are being encouraged by laws that do not require political parties and candidates publicly review the amounts of private donations received.

Reform and regulation being instigated to improve transparency and accountability being championed by NGOs such as Transparency International and others now require disclosure of private sources of funding. For instance in Britain, public disclosure is required for funds contributed corporate and unions through submission of detailed quarterly reports with name and address of donor and the relations. Elsewhere, in Germany, parties are free to canvass for private funding however, any donation that exceeds 10,000 Euros a year must be publicly disclosed together with the name and address of donor.

In Jamaica, a law, which was passed in the legislature in January 2016, introduced a host of measures. For example it sought to “limit expenditure by candidates, in any constituency, on election expenses to $10 million, or such sum as the Electoral Commission of Jamaica (ECJ) may, by order, subject to affirmative resolution, prescribe”. The Act also now requires all political parties to be registered and provided the ECJ with a campaign expenditure report with names, addresses and occupation of donors exceeding $250,000.

Following are some recommendations to further strengthen political parties funding transparency and accountability:

- The governments must adopt or improve in their national legal systems, rules against corruption in the funding of political parties and electoral campaigns.

- Political parties should voluntarily develop procedures for enhanced internal democratic, transparent decision-making and financial management. This will avoid a situation where legislation when introduced is seen as punitive.

- Complete transparency of political parties financing should be ensured with a view to avoiding any undesirable influence of money on party politics and policy.

- Political parties should employ qualified employees to run technical aspects of the party affairs for example finance.

- In the case of such countries such as Zimbabwe were political parties are not required to register, laws that require political parties to register should be enacted for easy regulation.

- Civil society and media should highlight irregularities and abuses of political party’s funds.

Discretionary power over use of funds by political parties must be exercised justly, fairy, honestly, and, above all, rationally in order to build viable and democratic institutions. Public awareness on the issues of prevention and the fight against corruption associated with funding of political parties is essential to the good functioning of democratic institutions.

References

- Austin, R and Tjernström, M. eds. 2003. Funding of political parties and election Campaigns, a handbook series: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance.

- Biezen, I. n.d. Campaign and party finance. Harvard University: (n.d- indicates no date).

- Biezen, I. 2003. Financing political parties and election campaigns: guidelines: Council of Europe Publishing.

- Bristow, M. 2016. Malaysia scandal highlights political funding problems. 25 March.

- Bryan, S and Baer, D. (eds) 2005. Money and politics: a study of party financing practices in 22 countries, National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI), USA.

- EISA South Africa. 2014. Updates issue 5. Resources: State and private-Use or abuse?

- Jamaica observer. 2016. PNP scandal gives urgency to campaign financing reform. 30 August.

- Masunungure, E.2006. Regulation of political parties Zimbabwe: registration, finance and other support, prepared for the Zimbabwe Election Support Network (ZESN).

- Mashaya, B. 2016. Companies pressured to fund Zanu-pf conference. Daily News live, 07 December, 2016

- Transparency International (Denmark). 2012. Secretive political financing opens door for scandal, says first Denmark corruption study.

- Zelizer, J. 2012. It took a scandal to get real campaign finance reform. 23 January.

جماهير الاهلى says

What’s up,I check your blogs named “Fixing Political Party Funding For Transparency and Accountability” daily.Your humoristic style is witty, keep doing what you’re doing! And you can look our website about جماهير الاهلى.